DOMESTIC X WILDCAT HYBRIDS

Domestic cats can be hybridized with a number of small wildcat species. Some hybrids occur under artificial conditions, others occur naturally. Such hybrids are sometimes used to explain Alien Big Cat (ABC) sightings in the UK. Though hybridization could explain some striking looking domestic cats, cats are variable creatures. As feline geneticist Roy Robinson wrote "colour or size variations cannot be construed as evidence of hybridity" (Genetics for Cat Breeders, 3rd Ed) and such variations can be accounted for in terms of gene mutation and recombination. Since the 19th Centry, cat fanciers and scientists alike have attempted to cross domestic cats with small wildcats. The terms "domestic" and "moggy" refer to F. catus in both pet and feral forms. Dr. Mircea Pfleiderer, who worked for many years as an assistant to the well-known cat researcher Professor Paul Leyhausen, knows the possibilities in hybrid breeding. "Professor Leyhausen knew very early that we can mate wild cats with domestic cats." Leyhausen had never published his findings, because: "If will not be a good development if people find this out.”

Hybrids With Unidentified Wild Cats

In 1889, Harrison Weir wrote in "Our Cats and All About Them" "In the year 1873, there was a specimen shown at the Crystal Palace Cat Show, and also the last year or two there has been exhibited at the same place a most beautiful hybrid between the East Indian wild cat and the domestic cat. It was shown in the spotted tabby class, and won the first prize. The ground colour was a deep blackish-brown, with well-defined black spots, black pads to the feet, rich in colour, and very strong and powerfully made, and not by any means a sweet temper. It was a he-cat, ant though I have made inquiry, I have not been able to ascertain that any progeny has been reared from it, yet I have been informed that such hybrids between the Indian wild cat and the domestic cat breed freely."The more recently developed Habari claims to be bred using DNA profiling for preferred genetic traits rather than pedigrees and does not declare which wild species are involved. Its name comes from the Swahili word for "what's the news?" ("What's up?"). At 25 lb and 16-18 inches at the shoulder, the Habari aims to be even larger than the Savannah or Safari and aims to have a spotted/rosetted pattern on a cream or golden background colour. However the ancestry of the breed is a trade secret to prevent copyists. Images of the Habari also suggest they are F1 or F2 hybrids foundation breeds/cats probably include the Bengal or Asian Leopard Cat; the Savannah or Serval (for size) and possibly others.

The Habari is bred for size, appearance and disposition and has not sought cat registry recognition. The breed registry claims to be based on DNA profiling to ensure the foundation cats produce kittens that meet the Habari aim (there apparently being no pre-set standard). Those not meeting the Habari profile will not be registered as Habaris and will be petted out. Breeding for type and not registering variants is nothing new; it is standard practice in cat breeding. DNA profiling in the form of karyotyping (chromosome counting) has previously been suggested as a way forward for the Safari breed as Safaris inheriting higher chromosome counts were larger in size. The discredited Ashera breed also claimed to use genetic technology. The alleged extremely rigorous selection processes means that the supply of Habari kittens will be very limited and therefore very expensive, with a 2-year waiting list and requiring pre-birth deposits. These claims and practices are all worryingly close to those made for the Ashera (that turned out to early generation Savannahs re-sold under the Ashera name).

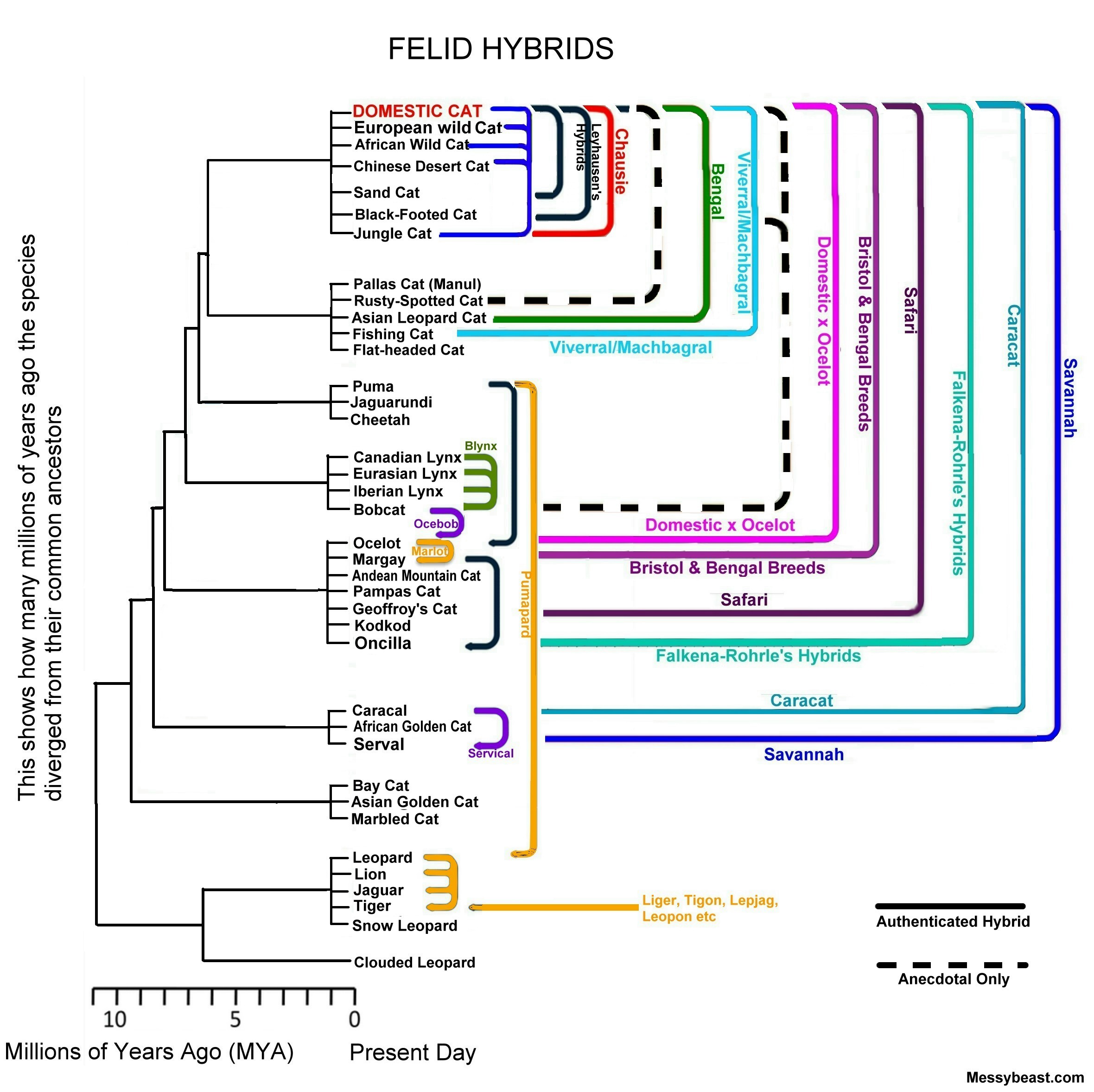

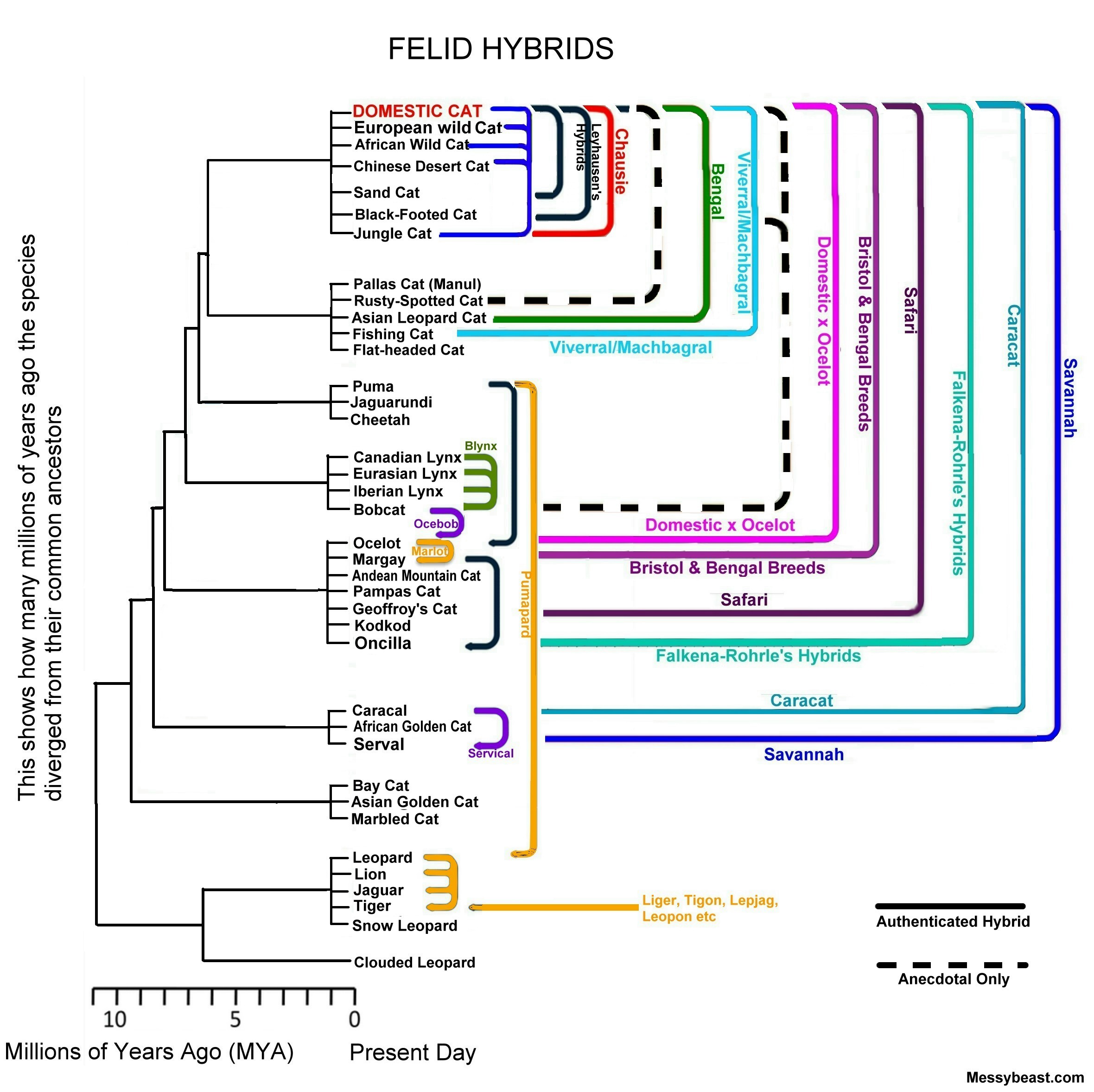

Taxonomy and Evolution of the Domestic Cat

The probable ancestor of domestic cats is the African Wildcat (F lybica/F silvestris lybica) which, through mutation and selection, has given rise to modern F catus. Professor Eric Harley considers F catus to be a natural sub-species of F lybica. The intractable European Wildcat (F silvestris/ F silvestris silvestris) can interbreed with F. lybica and may have contributed to the gene pool. In 1991, Tabor argued that the amenable Jungle Cat (F chaus) influenced domestic cat evolution ("Cats: the Rise of the Cat" Roger Tabor (BBC TV series & book)). Characteristics found in the Abyssinian breed (ticked colouration, ear-tufts) support this view (seeDomestication of The Cat).

Both Pallas's Cat (F. manul) and Sand Cat (F. margarita) may have contributed to the domestic cat gene pool as ancestors of longhaired cats, though this is refuted by modern zoologists. The German naturalist Peter Pallas, who discovered Pallas's Cat in the 18th century, recorded that it would breed with domestic cats and it was once believed that the longhair trait had come from Pallas Cat matings. Similar suggestions have been made regarding the Sand Cat (F. margarita) as an ancestor of longhairs. Roger Tabor suggested the Asian Golden Cat (F. temmincki) may have contributed to Siamese/Oriental breeds, hence the distinct "Oriental" type ("The Wildlife of the Domestic Cat", Roger Tabor). However, the link between the Siamese and Temminck's cat is more likely due to naming confusion in the early 1900s. In Ceylon, the Siamese cat was known as "Gould's Cat", having been introduced there by a Mr Gould. The Burmese Sacred Cat (the Burmese, not the Birman) was known to early British cat fanciers as the "Gold Cat". A wild cat of the region was known as the "Golden Cat" (Temminck's Golden Cat) or "Bay Cat". HC Brooke, writing in 1927, believed these similarities of name to be the reason that Temminck's Golden Cat (or Bay Cat) was claimed to be an ancestor of the Siamese.

Since being domesticated, mutation and selection (natural and artificial) produced different sizes, shapes, colours and fur-types of domestic cat. From time to time, breeders have crossed them to various types of wildcat. In the 1800s it was believed that domestic cats in each country evolved from indigenous wildcat population e.g. from Scottish wildcats in Britain and from Jungle cats in India, thus, crossing domestic tabbies to Scottish wildcats was seen as back-crossing rather than hybridisation. Domestic cats can interbreed with several species of small wildcat and produce fully fertile hybrids with some of them.

According to Charles Darwin in "The Variation Of Animals And Plants Under Domestication" (1860s), "Several naturalists, as Pallas, Temminck, Blyth, believe that domestic cats are the descendants of several species commingled: it is certain that cats cross readily with various wild species, and it would appear that the character of the domestic breeds has, at least in some cases, been thus affected. Sir W. Jardine has no doubt that, "in the north of Scotland, there has been occasional crossing with our native species (F. sylvestris), and that the result of these crosses has been kept in our houses. I have seen," he adds, "many cats very closely resembling the wild cat, and one or two that could scarcely be distinguished from it." Mr. Blyth (1/89. Asiatic Soc. of Calcutta; Curator's Report, August 1856. The passage from Sir W. Jardine is quoted from this Report. Mr. Blyth, who has especially attended to the wild and domestic cats of India, has given in this Report a very interesting discussion on their origin.) remarks on this passage, "but such cats are never seen in the southern parts of England; still, as compared with any Indian tame cat, the affinity of the ordinary British cat to F. sylvestris is manifest; and due I suspect to frequent intermixture at a time when the tame cat was first introduced into Britain and continued rare, while the wild species was far more abundant than at present." In Hungary, Jeitteles (1/90. 'Fauna Hungariae Sup.' 1862 s. 12.) was assured on trustworthy authority that a wild male cat crossed with a female domestic cat, and that the hybrids long lived in a domesticated state. In Algiers the domestic cat has crossed with the wild cat (F. lybica) of that country. (1/91. Isid. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 'Hist. Nat. Gen.' tome 3 page 177.) In South Africa as Mr. E. Layard informs me, the domestic cat intermingles freely with the wild F. caffra; he has seen a pair of hybrids which were quite tame and particularly attached to the lady who brought them up; and Mr. Fry has found that these hybrids are fertile. In India the domestic cat, according to Mr. Blyth, has crossed with four Indian species. With respect to one of these species, F. chaus, an excellent observer, Sir W. Elliot, informs me that he once killed, near Madras, a wild brood, which were evidently hybrids from the domestic cat; these young animals had a thick lynx-like tail and the broad brown bar on the inside of the forearm characteristic of F. chaus. Sir W. Elliot adds that he has often observed this same mark on the forearms of domestic cats in India. Mr. Blyth states that domestic cats coloured nearly like F. chaus, but not resembling that species in shape, abound in Bengal; he adds, "such a colouration is utterly unknown in European cats, and the proper tabby markings (pale streaks on a black ground, peculiarly and symmetrically disposed), so common in English cats, are never seen in those of India." Dr. D. Short has assured Mr. Blyth (1/92. 'Proc. Zoolog. Soc.' 1863 page 184.) that, at Hansi, hybrids between the common cat and F. ornata (or torquata) occur, "and that many of the domestic cats of that part of India were undistinguishable from the wild F. ornata." Azara states, but only on the authority of the inhabitants, that in Paraguay the cat has crossed with two native species. From these several cases we see that in Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, the common cat, which lives a freer life than most other domesticated animals, has crossed with various wild species; and that in some instances the crossing has been sufficiently frequent to affect the character of the breed.

Whether domestic cats have descended from several distinct species, or have only been modified by occasional crosses, their fertility, as far as is known, is unimpaired. The large Angora or Persian cat is the most distinct in structure and habits of all the domestic breeds; and is believed by Pallas, but on no distinct evidence, to be descended from the F. manul of middle Asia; and I am assured by Mr. Blyth that the Angora cat breeds freely with Indian cats, which, as we have already seen, have apparently been much crossed with F. chaus. In England half-bred Angora cats are perfectly fertile with one another."

Natural Hybridization

Hybrids occur naturally in rural areas where free roaming domestic cats or feral cats meet up with small wildcats that are willing to mate with them. According to Clark, Borodin and other authorities, population studies of domestics in such areas indicate the heavy influence of wild type genes (possible mutation forms of a gene). However, appearance alone is not evidence of hybridization. According to cat population authority Neil B. Todd, introgressive hybrids may also occur in rural South America where European settlers imported domestic cats for their farms and ranches. Occasionally a small cat, identified as a Geoffroy's Cat, turns out to be a possible hybrid (female Geoffroy's Cat x domestic cat hybrids are fertile).

Where small wildcats have been introduced to a region, they have bred with local wildcats or domestic cats. 18th Century sailors sometimes acquired Jungle Cats from villages in India where the cats scavenge around villages and towns, much like urban foxes in Britain. These cats, kept as ratters or trade goods, may have jumped ship at various British ports, breeding with the feral colonies which congregate around dockyards. Early British sightings of Jungle Cats (also called Swamp Cats) tend to be centred around ports. During the latter part of the 20th Century, a number of Jungle Cats have been seen in Britain, including some found as road kill. Presumed Jungle Cat hybrids have been seen among feral cats in these areas.

The first-cross (F1) hybrids between domestic cats and the larger Jungle Cat are vigorous, large and fertile, though subsequent generations become smaller through continued interbreeding with the more numerous domestic cat. Eventually the Jungle Cat genes are so dilute that the hybrids are indistinguishable from moggies. Roy Robinson noted that hybrid animals do not breed true and in succeeding generations there is a selective return to the original genetic combination prevalent in the area (Genetics for Cat Breeders, 3rd Ed). Repeated backcrossing to one species brings each subsequent generation closer in type to that species. In Britain, contined interbreeding with domestic cats has caused Scottish Wildcats to exhibit progressively more domestic cat traits including smaller size, tapered tail with fused black banding and white markings.

Introgressive hybridization means the movement of genes between two species by frequent hybridization and backcrossing. It occurs in small populations or in boundary areas where two species come into frequent contact and a stable, self-perpetuating intermediate form arises. The Kellas Cat, a black wildcat found in Scotland, is believed to have arisen this way.

In the 1990s, cryptozoologist Karl Shuker suggested that escaped Leopard Cats (F. bengalensis) may lead to natural Leopard Cat hybrids in Britain, citing the development of the Bengal breed to support this ("The Lovecats", Fortean Times 68, pages 50-51). While the Bengal originates from such hybrids, they rarely breed successfully without human intervention. In the definitive book of the breed. The F1 males are sterile and the F1 females are poor mothers and prone to commit infanticide. A more likely, and very dilute, source of Leopard Cat genes is the Bengal breed itself (no more thn 12.5% wild blood). Bengal x moggy offspring will not be ferocious giants since, contrary to wildly inaccurate press reports, Bengals are affectionate, unaggressive and normal pet cats. In 2003, the BBC and other news agencies reported "90%" wild-blood "Bengals". Cats with such high percentages of wild blood are not pets, they are produced by back-crossing successive generations of Bengals to pure-bred Asian leopard cats and are used in breeding programmes. The percentage of wild blood in pet Bengals is closer to 12.5%

Hybridisation of domestic cats with wild species is not a new phenomenon. There was interest in wildcats and hybrid breeds right from the start! The Crystal Palace show of 1875 included a class for "Wild or Hybrid between Wild and Domestic Cats" which was won by an ocelot. The first major American cat show at New York in1895 included ocelots and other wild cats. Between 1873 and 1904, the Scottish Wildcat was experimentally crossed with various domestic breeds (including the Siamese) and some of these hybrids were exhibited at early British cat shows. At the turn of the 20th century, Claude Alexander crossed an Abyssinian cat to an imported African Wild Cat and registered the female offspring, Goldtick, as an Abyssinian. Goldtick was later bred as an Abyssinian.

According to Fernand Mery in “Just Cats” (1957), “All authorities agree on this point: the domestic cat is not a descendant of the [European] wildcat. Every time attempts have been made to cross-breed the two species, to couple wild and domestic cats, the results have been most disappointing. The domestic cat can be mated with the wild cat of the jungle, with the Asiatic cat and even with the lynx; but the offspring of these difficult marriages usually die very young, and the experiment can never survive the first generation.”

In the Long Island ocelot Club newsletter 23/2 April 1979, Pat Warren wrote "The Color Genetics of Hybrids" based on her F1 Geoffroy's Cat hybrids and F1 Leopard Cat hybrid. This was the first real attempt to understand the interaction of the wild and domestic colour and pattern genes. She asked "Why do the hybrids come out in different colors?" and noted that although the colour genetics of domestic cats were complex they were fairly well understood and colours and patterns of offspring was predictable. The color genetics of exotics, by which Warren meant wild cat, were less well understood, but from the few hybrids bred it was apparent the modes of inheritance functioned similarly. Through small cat hybrids, Warren believed breeders could learn much about the colour genetics of the small wild cats including the white Bengal tiger and the white lions of Timbavati.

Lily's mother was a black self American Shorthair ansd her father was a Geoffroy's Cat. Lily had black spots. Gaucho's mother was Siamese - in genetic terms a solid black with two copies of the recessive colourpointing gene. His father was a Geoffroy's cat. Since breeding black-to-black results in only blacks or in recessive blues, this meant the Geoffroy's Cat spots were genetically black. The colourpointing remained recessive and since Gaucho only had one copy, this wouldn't show up. The wild spotting pattern was apparently dominant to all domestic colours and patterns except dominant white. The Douglases had had two solid white Bengals bred from Leopard Cat Shah and a white Turkish Angora. Warren noted that when When the wild colour gene is inserted into the dominance order for domestic color genes, it probably looks like this:

Dominant White > Wild marking pattern > Silver > Full colour (including tabbies) > Burmese > Siamese > Albino

|

Parent 1 |

Parent 2 |

Offspring (if named) |

Additional Notes |

|

European Wildcat (F silvestris) |

Jungle cats (F chaus) |

Euro-Chaus |

Not to be confused with Euro-Chausie below! |

|

Jungle Cat (F chaus) |

Bobcat (F rufus) (alleged) |

Jungle Lynx. |

Bobcat ancestry disproved by genetic testing. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Asian Leopard Cat (F bengalensis) |

Bengal |

Bengal has been used in developing the Toyger and the Serengeti. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Asian Leopard Cat (F bengalensis) Amur subspecies |

Ussuri |

(Unconfirmed) |

|

Domestic Cat |

Margay |

Bristol |

The Bristol was not developed and hybrids were absorbed into the Bengal breed. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Ocelot |

(unnamed) |

Accidental mating (male ocelot, female domestic) in 2007. Repeated in 2008 to confirm sire's identity. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Jungle cat (F chaus) |

Chausie, Jungle Curl, Stone Cougar |

|

|

Domestic Cat |

Jaguarundi |

Jaguarundi Curl (alleged), Mandalan Jaguar (proposed) |

No confirmed hybrids of these cats (2013) |

|

Domestic Cat |

Geoffroy's cat (F Geoffroyii) |

Safari |

Pre-dates the Bengal, there is renewed interest in this hybrid. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Bobcat (F rufus) (alleged) |

Anecdotally the Legend Cat, American Lynx, Desert Lynx, Alpine Lynx, Highland Lynx, American Bobtail and Pixie-Bob (genetic analysis disproved Bobcat ancestry). |

|

|

Domestic Cat |

Northern Lynx |

- |

Circumstantial evidence only (pre-dated DNA testing). |

|

Domestic Cat |

Serval |

Savannah, Ashera (possibly also Habari) |

Domestic parent may be Bengal |

|

Domestic Cat |

Caracal |

Caracat (USA hybrids) |

Moscow Zoo, 1998 (female caracal, feral tomcat). USA 2007, male caracal, female Abyssinian |

|

Domestic Cat |

Little Spotted Cat (Tiger Cat/Oncilla) |

- |

Holland, 1964 - 1966; 7 kittens born (2 litters). Only 3 female hybrids survived; all were sterile. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Blackfooted Cat (F nigripes) |

- |

|

|

Domestic Cat |

Rusty-Spotted Cat |

- |

Unconfirmed. Little is known about the Rusty-spotted cat or its habits. Range overlaps with domestic cats - may interbreed naturally. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Sand Cat |

- |

Anecdotal historical accounts. Proven hybrids born 2013 in captivity. Sand Cat range overlaps with domestic cats - may interbreed naturally. |

|

Domestic Cat |

African Wildcat (F silvestris lybica) |

- |

Mongrel wildcats are supplanting the pure African Wildcat in its native habitat. |

|

Domestic Cat |

Scottish Wildcat (F silvestris grampia) |

- |

Mongrel Wildcats are supplanting the pure Scottish Wildcat. |

Some of the already hybrid breeds have then been crossed with other wild species to create complex hybrids between domestic cats and multiple species of wildcat.

|

Parent 1 |

Parent 2 |

Offspring (if named) |

Additional Notes |

|

Bengal |

Fishing cat (F viverrina) |

Machbagral, Viverral, Jambi |

|

|

Bengal |

Serval |

Savannah |

(Also listed in the table above as the Bengal is a domestic cat) |

|

Bengal |

Jungle Cat (F chaus) |

?? |

|

|

Bengal |

Chausie |

Jungle |

Began with an accidental mating. |

|

Bengal |

Geoffroy's Cat (F geoffroyii) or Safari |

?? |

|

|

Bengal |

Canadian Lynx |

?? |

Unconfirmed. |

|

Bengal |

Bobcat (alleged) |

DNA testing has disproved all alleged Bobcat-crosses to date (2013). | |

|

Jungle Cat hybrids |

Desert Lynx (domestic breed) |

Highland Lynx. |

DNA testing disproved Bobcat ancestry of Highland Lynx. |

|

Pixie-Bob |

Jungle Cat (F Chaus) |

Jungle Bob |

|

|

Hemingway/American Curl |

Jungle Cat (F Chaus) |

Jungle Curl |

|

|

Pixie-Bob |

Asian Leopard Cat (F bengalensis) |

Pantherette |

|

|

Chausie |

European Wildcat (F silvestris silvestris) |

Euro-Chausie |

Not to be confused with Euro-Chaus (European Wildcat x Jungle Cat) |

|

Chausie |

Bobcat (F rufus) (alleged) |

DNA testing has disproved all alleged Bobcat-crosses to date (2013). | |

PATERNITY / MATERNITY TESTING

With some species where DNA has previously been analysed, it is possible to test for marker genes in presumed hybrid offspring. At present the relationship between F silvestris wild species and domestic cats is to close for reliable results and F chaus markers might not be detected either. Tests have been done for bobcat markers in presumed bobcat hybrids, but there is apparently no test (yet) for lynx markers.

Where the wildcat sire is present i.e. in a captive mating, it might be possible to do a paternity test using a sample of that cat's DNA. The same applies in ascertaining paternity where a male domestic cat is suspected of impregnating a captive wildcat female.

Where an owner suspects hybrid kittens and has both parents available, it may be possible to do a Parent Verification Test on the kittens. This can only confirm relationships where DNA is available from both presumed parents as well as from the kittens. In the USA, Cal Davis offers Parent Verification Tests along with several others. This is the feline equivalent of human paternity/maternity tests.

THE LESS SAVOURY SIDE OF HYBRIDS: DISPOSABLE DOMESTIC FEMALES AND BACKYARD BREEDERS

The popularity of hybrid breeds has a grim downside. While reputable breeders supervise matings (and the accidental loss of any domestic female is taken seriously) and use permitted outcrosses, there are backyard breeders that use any available domestic female, especially moggies because they are cheap. Placing a domestic female with a wild species male can be risky - some wild species males will kill domestic females rather than mate with them. Where there is a size difference, for example with servals, caracals and domestics, using a randombred female means it doesn't matter if the wild species stud accidentally kills them during or after mating (his large size and larger teeth can make the mating neck-bite fatal). The worst of this type of breeder simply put several domestic females of any type/breed with the wild stud overnight and hope that some will survive the experience and produce kittens. It is this sort of breeder that brings cat-breeding and hybrids into disrepute.

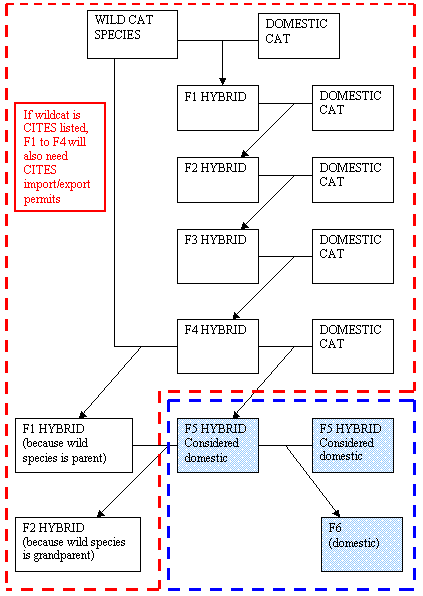

F1, F2, F3 AND BACKCROSSES

In Britain and some other parts of Europe, a cat with a non-pedigree ancestor in the last 3 generations (which includes a wild species) cannot legally be described or traded as a pedigree cat. This falls under Goods Description legislation which defines a pedigree cat as having at least 3 generations of pedigree ancestors.

AO, BO, CO as the first two characters of the TICA registration status code are Hybridisation record codes:

Ancestry and Hybridisation codes can be combined to show any outcrossing in the preceding 3 generations and whether the outcross was to a permissible breed, a non-permissible breed, a variant or a wild species e.g. A1P, C2P, B3P, A2N, A1S, B2V etc

F (Filial) Generations are used to describe wild x domestic hybrids

You are visitor number