HAIRLESS CATS

Hairlessness is a trait which has occurred in several places at different times. Hairless cats have been reported from Latin America in 1830. There are reports of this mutation occurring in France, Austria, the Czech Republic, England, Australia, Canada, USA, Mexico, Morocco, Russia and Hawaii. According to “La Vie a la Campagne” in 1935, “nude cats” were first mentioned by Poepig in “Illustrierte naturgeschichte Band” as occurring by chance, particularly in Bohemia. They were also noted by Fitsinger, who saw one in the town of Vienne. In addition, Devon Rexes are prone to baldness due to fragility of the hair and some LaPerm cats are born hairless.

Fur: Hairless Cats

Fur: Dwarf and Mini Hairless Cats

Fur: Hairless Cats: Fictional Hairless Cats

Fur: Hairless Cats: Mexican Hairless, or Aztec Cat

MEXICAN, CANADIAN AND AMERICAN HAIRLESS BREEDS

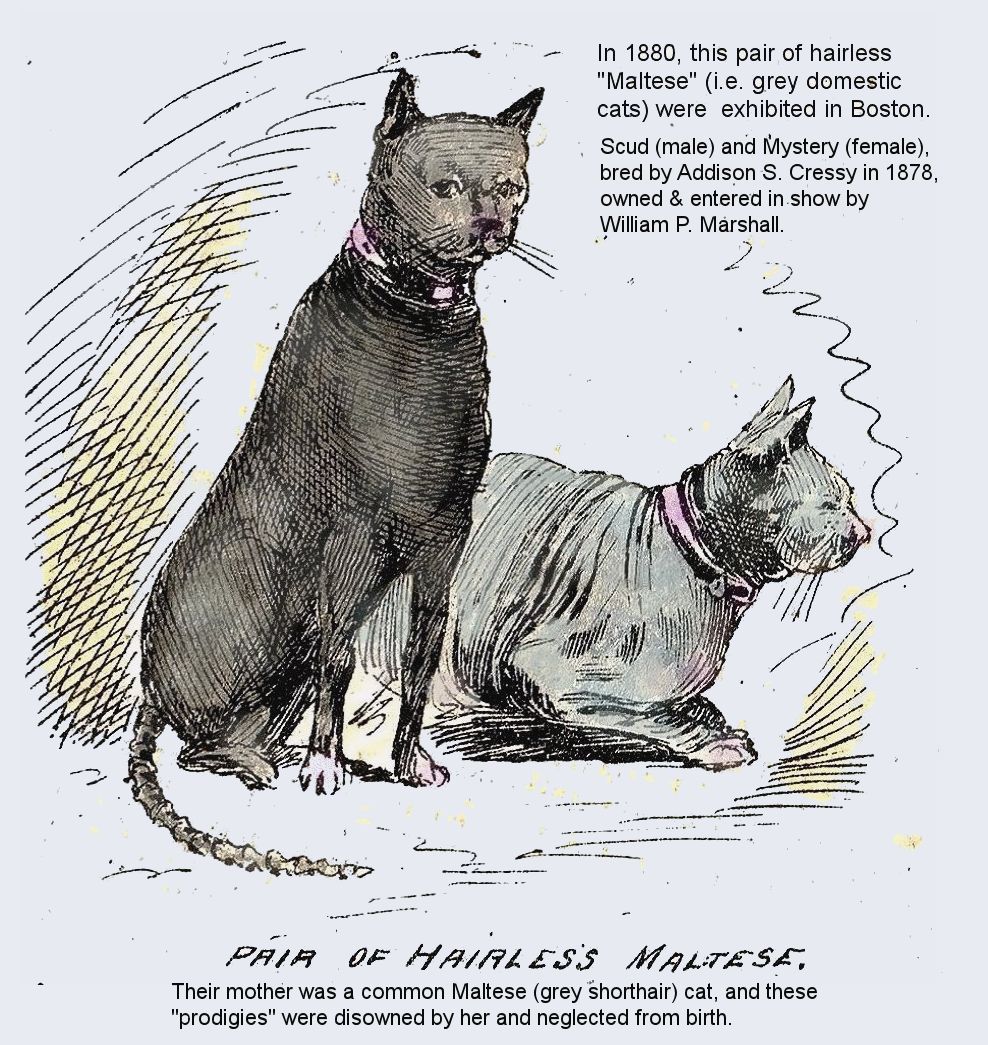

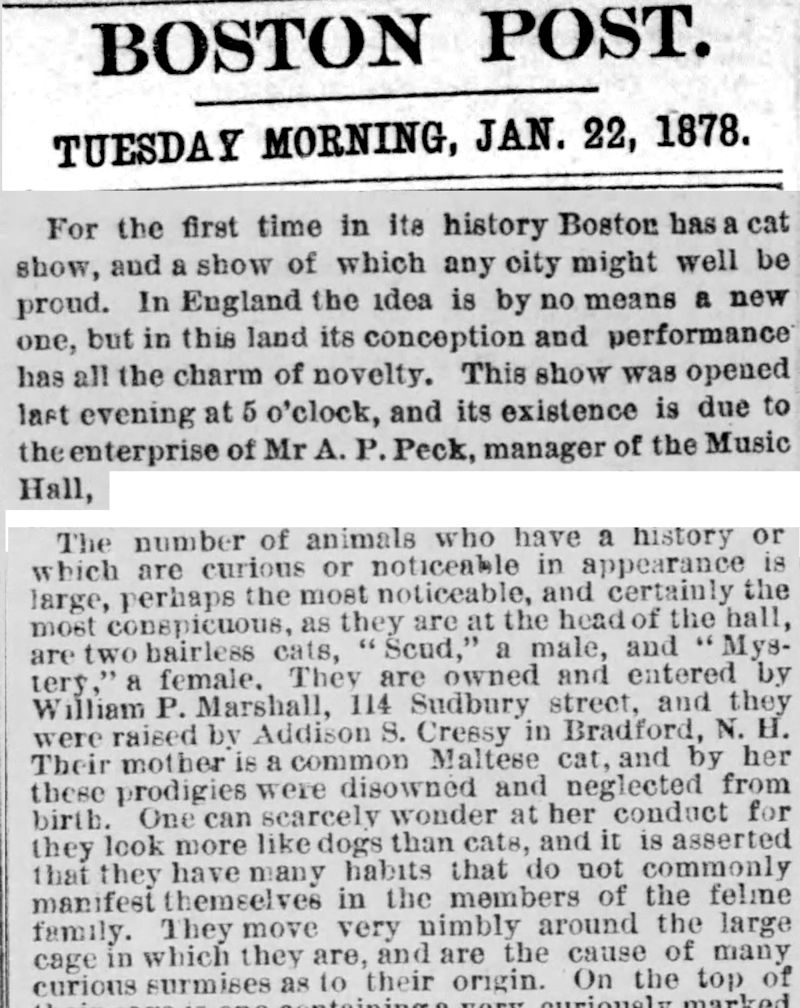

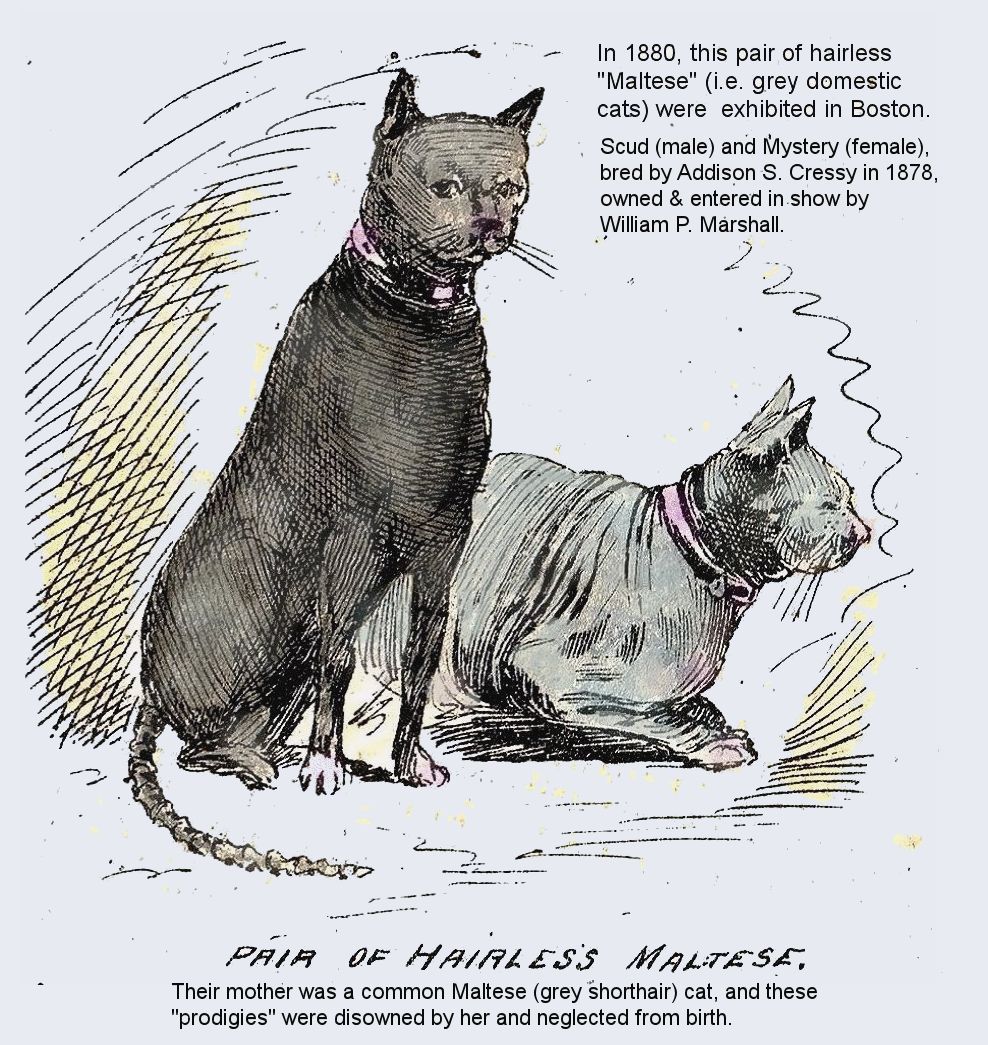

Although there are written accounts from the 1830's of a Paraguayan "scant-haired cat", the first detailed report of hairlesscats I have so far found is in 1878: "POOR PUSS. Boston Post, January 22, 1878 [...] For the first time in its history Boston has a cat show [...] its existence is due to the enterprise of Mr A. P. Peck, manager of the Music Hall, [...] The number of animals who have a history or which are curious or noticeable in appearance is large, perhaps the most noticeable, and certainly the most conspicuous, as they are at the head of the hall, are two hairless cats, “Scud,” a male, and “ Mystery,” a female. They are owned and entered by William P. Marshall, 114 Sudbury street, and they were raised by Addison S. Cressy in Bradford, N. H. Their mother is a common Maltese cat, and by her these prodigies were disowned and neglected from birth. One can scarcely wonder at her conduct for they look more like dogs than cats, and it is asserted that they have many habits that do not commonly manifest themselves in the members of the feline family. They move very nimbly around the large cage in which they are, and are the cause of many curious surmises as to their origin."

They have got a hairless cat in Kansas, and the difference between the Kansas man’s tile and the feline is that one is a careless hat and the other as above - Dundee People’s Journal, 23rd February, 1889

The Wilmington Messenger (Wilmington, North Carolina) of 1st October, 1893 describes an apparent random mutation (or a hairless puppy passed off as a cat) "We were shown yesterday a strange freak of nature in the shape of a hairless cat - or part dog and part cat, as really seems to be the case. The monstrosity very much resembles a hairless Mexican dog, but is cat shaped and is as playful as kittens in general. The ears are quite large and so are the paws, although at present there is no sign of claws. When the animal sits and raises its head it looks very much like a dog from the neck down to the forefeet. It was one of a litter of five kittens now four weeks old. The other kittens have hair and are natural in appearance and hardly half as large as their strange sister. The nondescript is not only large and stronger than the other four kittens but it is smarter and particularly full of life."

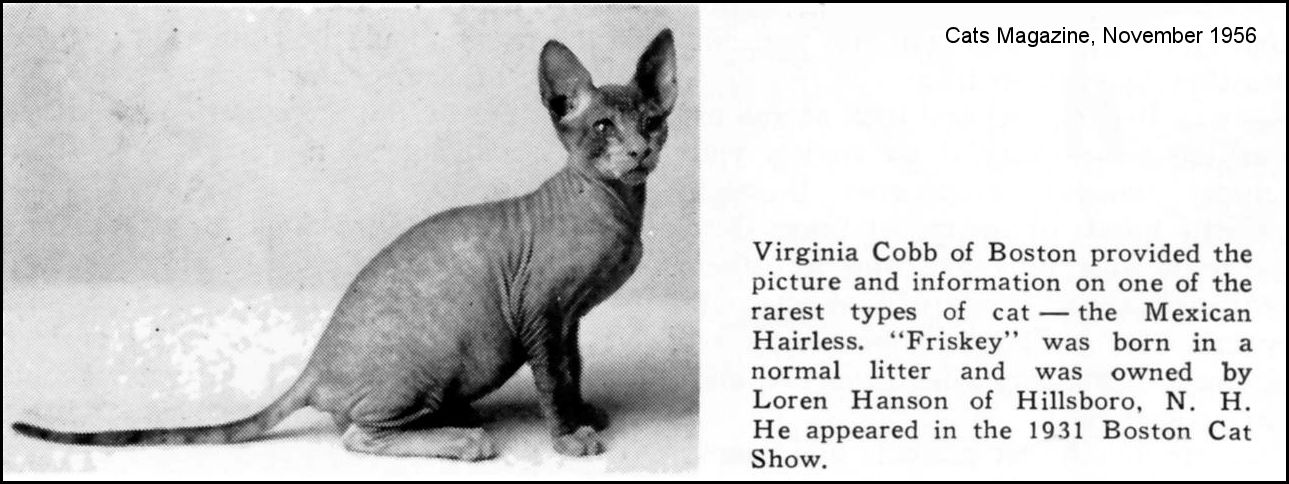

The first recorded hairless "breed" was the now extinct Mexican Hairless (also called the New Mexican Hairless). The full story is given on the linked page, but in brief in 1902, a Mr and Mrs Shinick from New Mexico received two hairless cats, Dick and Nellie from local Pueblo Indians. It was claimed that these were the last survivors of an ancient Aztec breed of cat. The Mexican Hairless cats were litter-mates and noted to be 25% smaller than local shorthair cats. They were normally whiskered and seasonally coated, growing a ridge of fur down the mid-back and tail during the colder seasons. The male was killed by dogs while young and the owners could not find a suitable hairless mate for the female. In fact the female could have been bred to similarly shaped domestic cats and the offspring back-crossed to their mother to re-establish the hairlessness trait. The Albuquerque Journal, 17th December, 1908 detailed Nellie’s planned train journey to Washington to meet the President and First Lady, and then to New York for the cat show. Nellie was to be in the care of well-known cat enthusiast Dr. Cecil French, who would take her to New York City to exhibit her at the annual cat show in Madison Square Garden commencing December 30. It was to be Nellie’s last journey. A follow-up article from The Albuquerque Journal, 29th December, 1908 tells us she was bred and raised by Mr. Shinick (an admission of her origin at last!) and had been unwell when she left Albuquerque by train and died the day after reaching Washington. The immediate cause of death was dropsy (wet FIP), but her spleen, liver, kidneys and uterus were all found to be diseased and even without dropsy, Nellie would not have lived much longer. Her body was donated to the Museum of Natural History/Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D. C., for display, but has since been lost.

The above illustration, from Charles Henry Lane's book "Rabbits, Cats and Cavies" (1903) is a portrait of a Mexican Hairless Cat called "Jesuit" that belonged to the Hon. Mrs McLaren Morrison. It was the only specimen the author had been shown and he believed it to be the only one ever exhibited in England. A lot of digging around in archives indicates that Jesuit was probably a random mutation, because Nellie was too valuable to leave the USA. SMrs. McLaren Morrison collected curious cats and would have snapped up any hairless cat to be found (this lady later became a cat hoarder). Sadly, the Mexican Hairless was lost through lack of a breeding programme. There was reputedly a pair in Europe, but whether these were genuine Mexican Hairless or a new mutation was unproven. In 2006, it was claimed that new examples of the Mexican Hairless had been found. This remains to be confirmed. A true Mexican Hairless cat grows a ridge of fur along the spine in winter.

Also in 1902, a breeder of blue Persians wrote to the magazine "Our Cats" that his cat "named Flossie had five most beautiful kittens, two light, three dark, with splendid heads. These all had lovely coats, but suddenly we found in the nest a perfectly light-blue kitten, all wrinkles, with a face like a monkey. The skin is blue, perfectly smooth and clean." Most likely the kitten did not surive long, or may even have been destroyed (at that time, the fate of most kittens that did not meet the standard). There have since been anecdotal reports of hairlessness occurring in Persians.

|

|

|

|

|

|

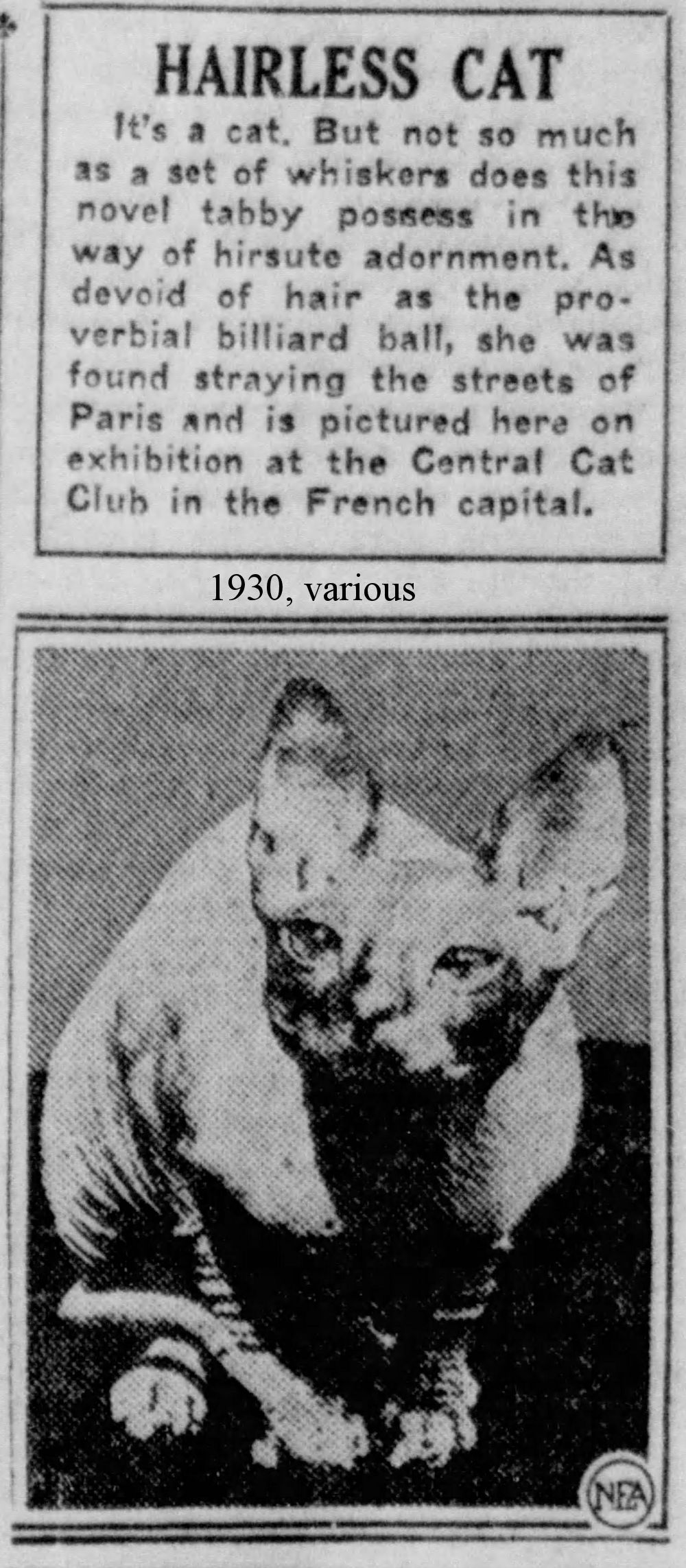

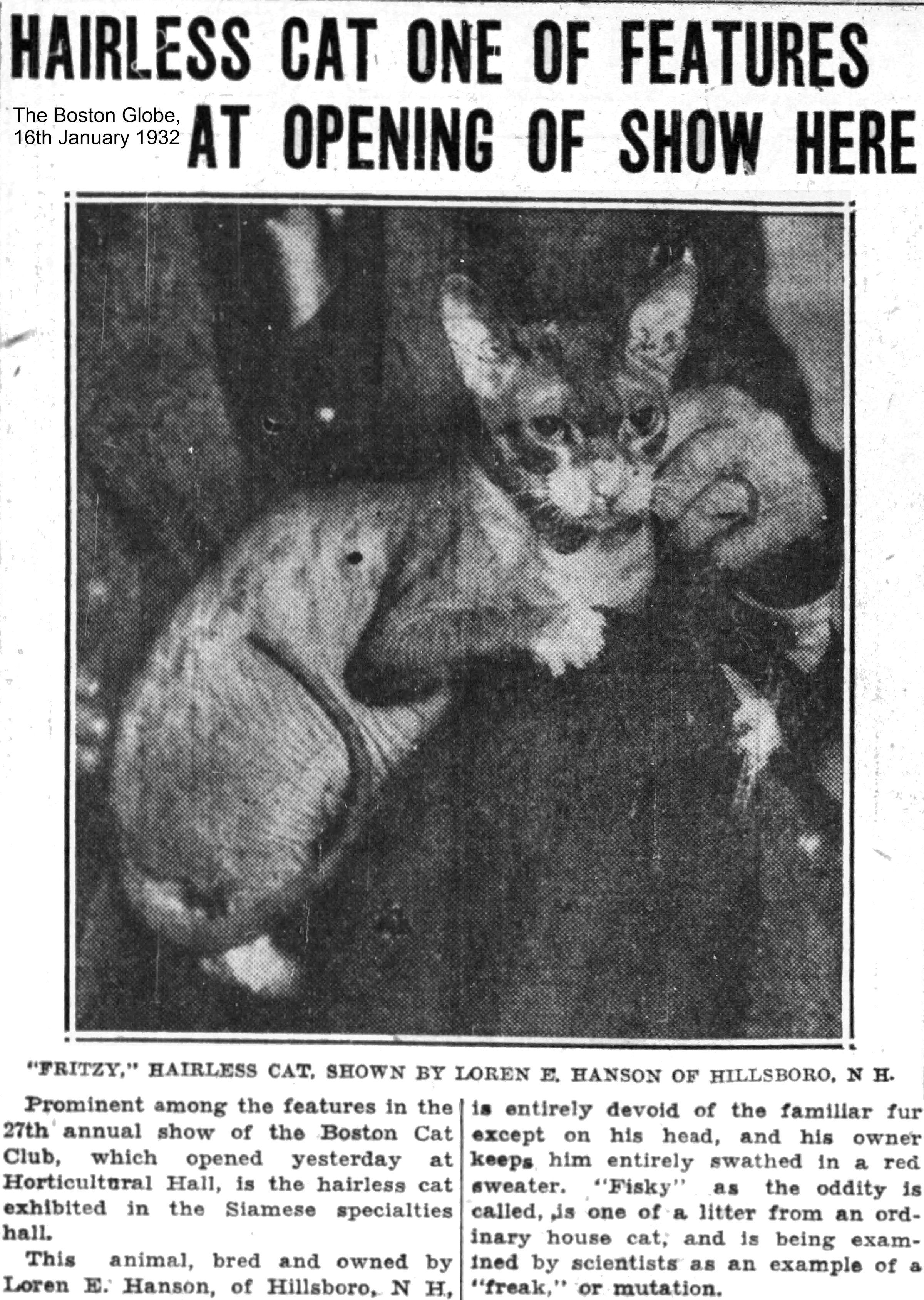

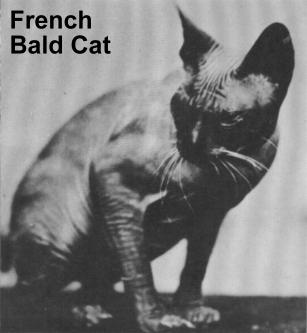

Santa Ana Register (California), 14th May, 1930 – “It’s a cat. But not so much as a set of whisker does this novel tabby possess in the way of hirsute adornment. As devoid of hair as the proverbial billiard ball, she was found straying the streets of Paris and is pictured here on exhibition at the Central Cat Club in the French capital.”

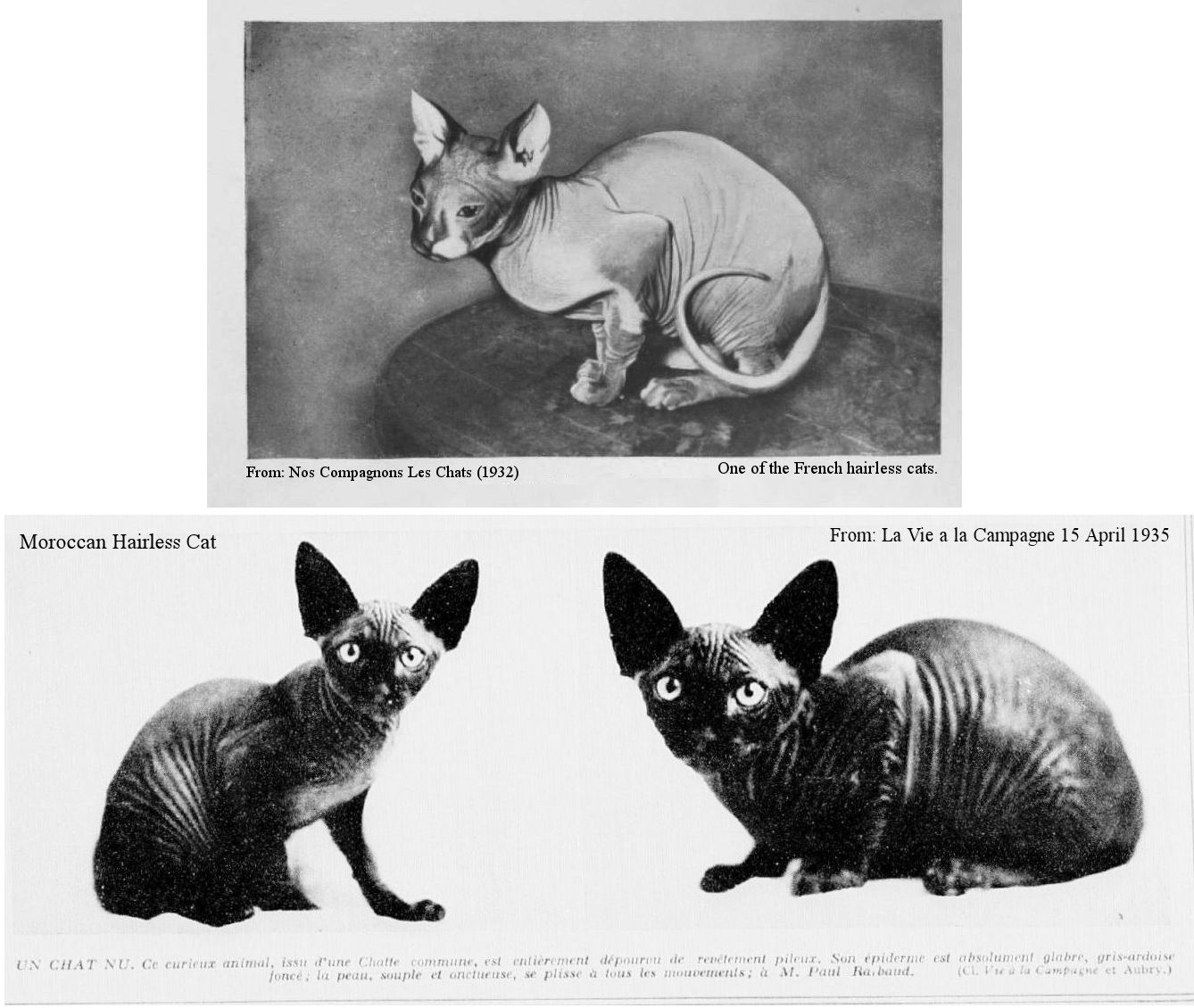

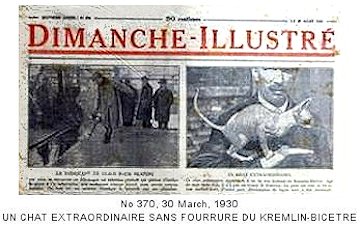

Hairless kittens (Bald Cats) appeared in in France (1932) but failed to thrive. In April 1935, the magazine "Vie A La Campagne" (Life in the Country) carried pictures from a 1932 cat show in Paris which had featured two hairless cats called "le chat nu" (the naked cat) shown as curiosities by Professor E Letard. The naked cats had been born to two different domestic females in the same household at Kremlin-Bictre, near Paris,in 1930 though both died without reproducing in 1931. The cats had been born 4 months apart and were exhibited at the Feline Exposition in Paris. This suggests a degree of inbreeding allowing a recessive gene to be expressed. Some later reports refer to the French Sphynx being "resurrected" , but this would refer to the resurrection of hairless cats in general, not to a French strain. The French Sphynx (Le Chat Nu) never became an established breed in its own right.

Vie A La Campagne also reported the occurrence of a hairless kitten born to a shorthair female in Fêz, Morocco as well as occasional sightings of hairless cats in parts of Western Europe. The Moroccan hairless cat was born on 7th April 1934 at the home of Monsieur Paul Raibaud. Among 5 perfect kittens was a curious one with long ears, large bright eyes and no fur or whiskers. M Raibaud took in the hairless kitten and it developed normally. At the time of the account in 1935, it was a grey-blue colour like that of slate. The skin was soft and supple. The teeth and claws were normal and the cat was active and healthy.

According to this paragraph from Schwangart's 1932 book "On Racial Constitution and Breeding of the Housecat" ("Zur Rassebildung und Rassezüchtung der Hauskatze") "Fig. 1 in the work SCHWANGART and GRAU (1931) showed a hairless cat with purely albino skin and noticeable symptoms of deterioration. (Its eyes were not albinotic). In this year's Paris International Show, I saw another specimen with vividly patched skin: pink and different tones of violet to blue, the areas clearly defined with sharp boundaries ("tile-like"), just as I saw in the furred specimens listed above. In contrast to the appearance of that albino-skinned specimen, this second animal had no external signs of deterioration in posture, shape or skin condition, except that its non-albinotic-looking eyes were hypersensitive to light. The dentition should be examined. (On the whole, this hairlessness is degenerative and is not desirable in breeding). As mentioned in the cited work, it is likely that the two animals were closely related." The cited work is SCHWANGART, F., and GRAU, H., 1931. — About malformations, especially hereditary tail deformities, in the domestic cat . — Journal for Animal breeding and.breeding Biology 22, pg. 203—249.

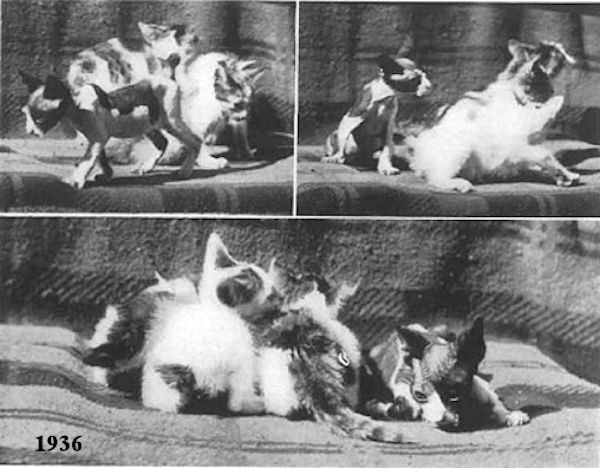

The letter From Henry Sternberceh of Wilmington, N. C. to The Journal of Heredity in 1936 titled 'A "Cat-Dog" From North Carolina Hairless Gene or "Maternal Impression"?'

Hairless Cat Or Cat-Dog: Three views of an abnormal kitten which appeared in a litter of four, only one of which was normal,—two of the others being short tailed. The genetic nature of this variation is unknown, but it has a striking resemblance to some of the genetic hairless forms in rabbits and mice.

Around the middle of August, 1936, a curious litter of kittens was born to a perfectly ordinary appearing pet cat, belonging to Mrs. Annie Mae Gannon, of Wilmington, N. C. Of the entire litter, only one of the kittens is perfectly normal in appearance - the other three being freaks. One of the cats has no tail at all; another has only a stub of a tail. But the extraordinary member of this feline family is the fourth—well, we can hardly call it a cat - so for want of a better name, we'll call it a "Nonesuch."

It is said that before the kittens were born, the mother cat was often engaged in fights by a mixed-breed dog in the neighbourhood, and on several occasions was badly frightened by the dog. This is about the only plausible explanation as to why the "nonesuch" is so unusual in appearance. In fact, this little animal - now about two months old – is about the queerest looking creature one could hope to set eyes upon. Its face is that of a black, white, and yellow spotted dog. Its ears are quite long and sharp pointed. It has the short whiskers of a puppy. The hind legs are amusingly bowed. It has a stub tail. What makes the nonesuch even more unusual appearing is the short smooth dog hair all over its cat-like body.

From the very moment of its birth, which was about twelve hours after the rest of the litter, the nonesuch was surprisingly independent in its actions. It was born with its eyes open, and was able to crawl a little - two characteristics quite unknown to new-born kittens. The nonesuch acts both like a cat and a dog. While it makes a noise like a cat, it sniffs its food like a dog. Nothing delights the nonesuch more than gnawing a bone in a very dog-like manner. When resting, little nonesuch places its paws straight out in front just as a dog would do. The little creature doesn't relish playing with the rest of its family, being entirely contented in stretching out and watching the others frolic about.

The Editor replied:

Geneticists would be more inclined to ascribe the appearance of the unusual animal described above to the action of a recessive mutation than to the ancient doctrine of maternal impressions. If the curious kitten does represent a mutation, it is one of no little genetic interest, as offering a further parallel between mutations in the cat and the rabbit. (See Keeler and Cobb, Journal of heredity 24 :181-184. May 1933). To judge from Mr. Sternberger's pictures and the description, "Nonesuch" must rather closely resemble the Rex rabbit. It was hoped that it might be possible to obtain "None-such" and test the matter genetically. Unfortunately his owner is reported to feel that this unusual creature should be so valuable for museum or sideshow purposes as rather to put it out of range of genetic experimentation. In a later letter from Mr. Sternberger we learn that all the other members of the litter have died, so that there seems little hope of being able to do more than record the occurrence of this odd form.

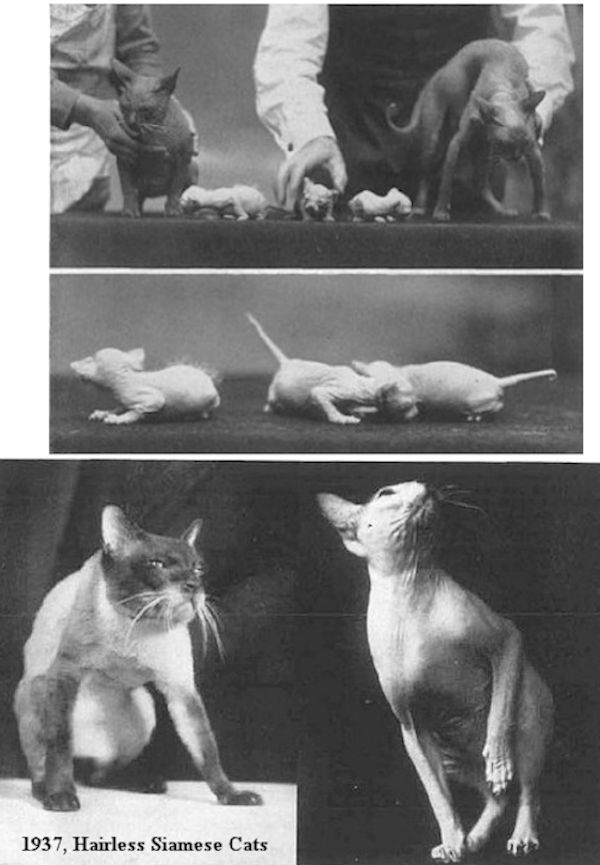

In 1938, Professor Etienne Letard (Professor at the National Veterinary School of Alfort (Seine) France) replied in the Journal of Heredity in a letter titled 'Hairless Siamese Cats'Hairless Siamese Kittens And Their Parents: Two views of hairless Siamese kittens twelve hours old, and their parents. All of them are hairless though one has a thin coat of short hairs. Note the fur distinctly visible on one of the kittens. This is especially thick on the ears and in the axes of the limbs. It disappears in a few days, being followed a short time later by another transitory coat. The two accounts of "Nonesuch", the alleged cat-dog hybrid in the Journal (March and September, 1937), have greatly interested the writer because he has had an opportunity to study a startingly similar variation in Siamese cats. The accompanying photographs show the appearance of the hairless cats, whose resemblance to "Nonesuch" is obvious. The origin and description of this hairless strain follows. A pair of Siamese cats, perfect in type with normal hair and coloring, produced from time to time one or two hairless kittens in a litter consisting otherwise of normal kittens. From these periodically appearing hairless individuals we have been able to create a strain of hairless cats, which we believe to be entirely pure.

"Carrier" And Naked Siamese Cats: On the left is a normally haired Siamese cat, which mated to a normal-haired male produced hairless offspring. She thus carries the recessive hairless gene. At right a mature hairless Siamese cat, the type of this recessive mutation. Note that the vibrissae ("whiskers") are normal. The whiskers of some hairless mammals are also affected. If one mates one of the two individuals who have produced this mutation, with other normal Siamese cats, a hairless kitten has never been produced. Only the mating of the two individuals in question produces the mutation. The crossing of a hairless animal with other normal individuals has never produced a hairless cat. We have mated two hairless cats, brother and sister; three hairless kittens were the result. With the exception of unforeseen circumstances which would have to be studied, the "hairless" can therefore be considered a type governed by the Mendelian law with hairlessness recessive to normal coat. Thus we find ourselves in possession of a strain, apparently already stable, which might be the origin of a distinct race, resuscitating the ancient race of so-called Mexican hairless cats, which is believed to be extinct.

It is imperative to mention that, though certain specimens are completely hairless, others have a slight down on their bodies. This down is subject to periodical changes, apparently closely connected with seasonal variations in temperature. Strange as k may seem, the young ones which grow into hairless cats are not so at birth, but have a growth of hair, less dense, however, than normal. A transitory pelage in young hairless rats has also been reported [Wilder, W., Et Al. A Hairless Mutation in the Rat. Journal of Heredity 23 :481- 484. 1932] The fact that the typical pattern of the Siamese cat is controlled in its development by temperature [1. Iljin, N. A. and V. N. Temperature Effects on the Color of the Siamese Cat Journal of Heredity 21 :309-318. 1930] may have a significance in this connection. This growth is most marked on the ventral surface and in the axils of the limbs. Between the tenth and fourteenth day after birth this juvenile hair has disappeared, and the "hairless skin" has become reality. The skin remains bald for several days and this is followed by another growth of hair. When the kitten has reached the age anywhere from eight to ten weeks it is covered with an abundant growth of hair which gradually disappears, until at the age of six months the final stage of adult nakedness has been reached; either the skin is completely hairless, or covered with a slight down, subject to seasonal changes.

The fact that this mutation was observed in animals which have always lived in Paris, proves again that it is not always in special environments that one has to search for visible variations, and emphasizes again the random nature of spontaneous changes in inherited characters which appear to be one of the basic mechanisms of organic evolution.

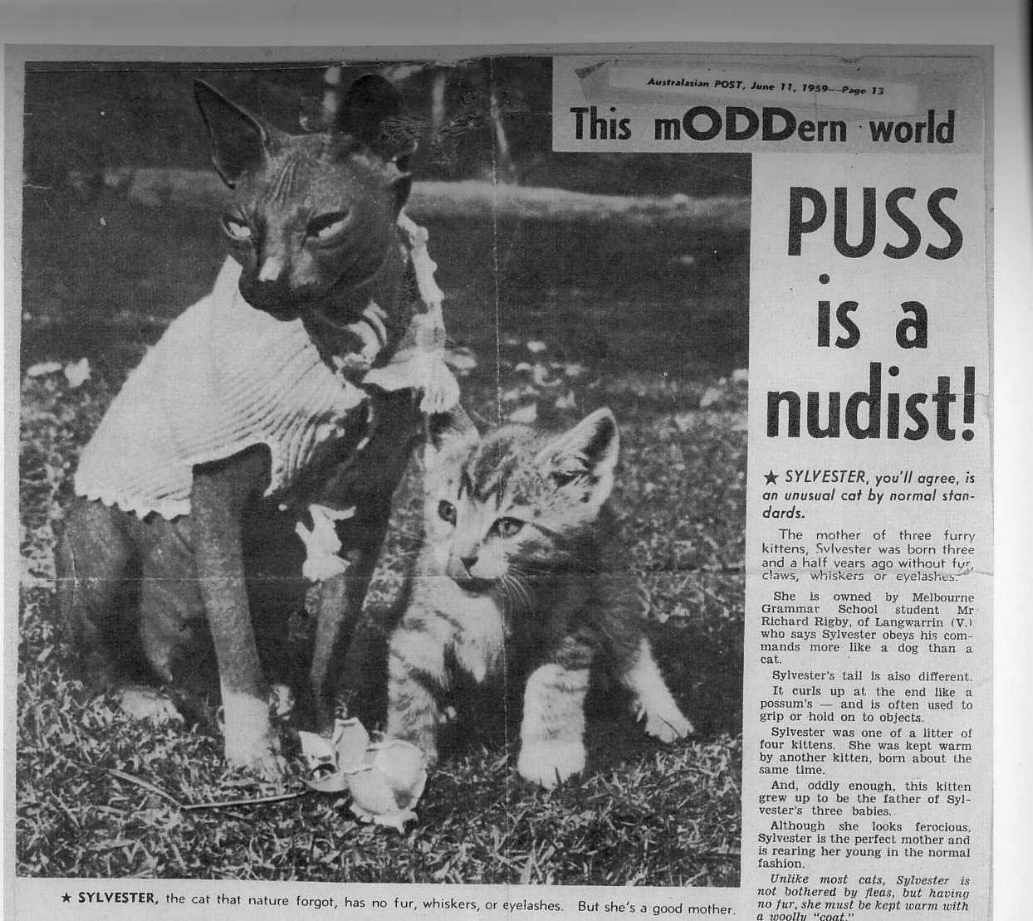

In June 1959, the Australian Post reported a hairless female cat called Sylvester. Sylvester was born in 1956 without fur, claws, whiskers or eyelashes. Her tail curled up at the end "like a possum's" and she curled it around objects. The cat (which appears to be a black with white locket and boots) was owned by Melbourne Grammar School student Richard Rigby of Langwarrin who reported Sylvester was dog-like in her ability to obey commands. Sylvester was one of four kittens in the litter and was kept warm by one of the other kittens. That other kitten, a male, was later mated to Sylvester and in 1959, Sylvester had 3 fully furred kittens. It was reported that Sylvester was not bothered by fleas and that she wore a woolly coat to keep her warm. The lack of claws suggests a general failure to produce keratin. Nothing further seems to have been heard of this mutation.

In his book “Just Cats” (1957), French cat-fancier Fernand Mery wrote “It is true that completely naked cats also exist: cats without fur, among which we have succeeded in determining a strange mutation linked to a recessive gene. Did the race of hairless cats actually exist in Mexico? Did it originate from the short-haired cats of Paraguay? This is not beyond the realms of possibility, as these hairless cats are not initially bare; they do not come into the world so, as Andre Sécat has pointed out. Initially they have a covering of down, which falls out after the first week. Afterwards there is another growth of down, which lasts for two months: time for the kittens to be weaned and sufficiently developed to survive. In its turn, this thin coat falls out during the next few weeks. When the cats have attained the age of six months, they are then, but then only, hairless cats, perfectly smooth-skinned. Are they beautiful? That is a different matter. But should you be tempted to possess one, it would be useless to look for it on the market. There are no hairless cats professionally bred. They are simply a curiosity of creation."

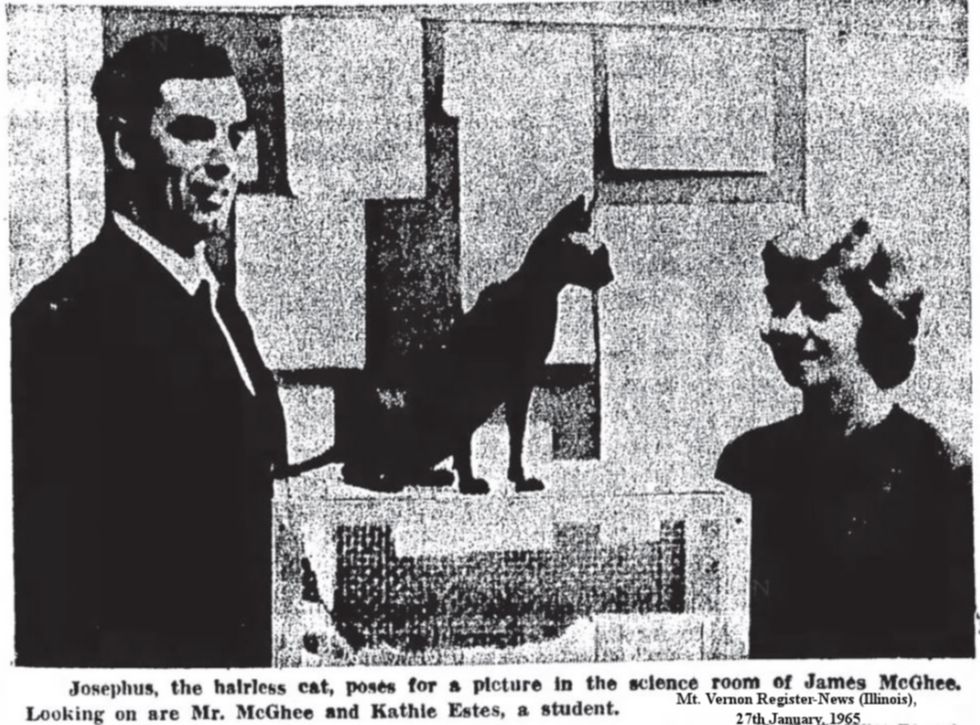

Another hairless cat to achieve local fame was Josephus, who was described in the Mt. Vernon Register-News (Illinois) on 27th January, 1965:

“Josephus, Ml. Vernon's one and only hairless cat, visited the science department of Mt. Vernon Township High School and Community College last Thursday. He spent the day in the general science room of James McGhee where most of the other science teachers came to make his acquaintance. Josephus, or Joe as he is called by his intimate friends, was born last July at West Frankfort. He was the only hairless kitten in the litter though one or two of his brothers and sisters were club-footed. At birth he was entirely devoid of hair and still is except for short whiskers and a little hair around his face. He is dark grey in color and tends to become lighter with age. He was almost black at birth.High school and college science teachers pronounce him a mutant. A mutant is the result of a mutation or sudden departure from its parents in one or more heritable characteristics caused by a change in a gene or a chromosome. The teachers wonder what kind of offspring would result if he were mated with an ordinary cat. Josephus is the pet of a Mt. Vernon family who acquired him last August when he was scrawny and frail and weighed only eight ounces. The family prefers to remain anonymous, because they do not wish to be annoyed by the merely curious. They are eager to cooperate with any persons with a truly scientific interest, but they cannot forget how the privacy of their home was invaded earlier last year by dozens of inconsiderate persons who came at all hours to see the cat. Josephus was disturbed too by the curious visitors who poked him in the ribs to arouse him when he was enjoying a little siesta. The family reports that the habits of Josephus differ from those of an ordinary cat. For Instance, he likes very much to play in shallow water, and when he is given more than he can eat, he makes great efforts to hide or cover up the left-over portion with a newspaper or anything else that is available. His: most cherished possession is a pheasant’s foot which he has had for a long time. He is rather shy, but if he likes and trusts a person he will make a show of affection by bringing the pheasant foot to him. As it might be expected, Josephus is cold natured. He often wears his sweater in the house and always seeks the warmest spots. Imagine a nudist crawling through deep snow drifts and you can visualize how winter traveling is for Josephus. What will happen when Josephus steps out into cat society? Will all the eligible and attractive young felines shy away in horror, or will they lionize him because he is different? Being hairless is fraught with problems and disadvantages, but it sets him apart from all others and gives him great renown. Let Olney keep her white squirrels; Mt. Vernon has a hairless cat”.

It was reported (in 1966, probably referring to the 1930s kittens) that Professor Étienne Letard of L'Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort in France had "resurrected" the breed of bald cats and it was noted that there were a few examples in Europe and America. The cats were reported as not born completely bald. The kittens had very light hairs which have scarcely thickened by the growth of a slight down during the first two months. After the kittens are weaned, this down falls away to leave them completely smooth. At the time, they are described as sensitive to cold, unaesthetic and not much admired by cat lovers and having only a technical interest. The report noted that the mutation had been fixed, but the breeding of bald cats was a flirtation for the specialist and did not have a great future.

An account of hairless Siamese appeared in a news report in 1966:

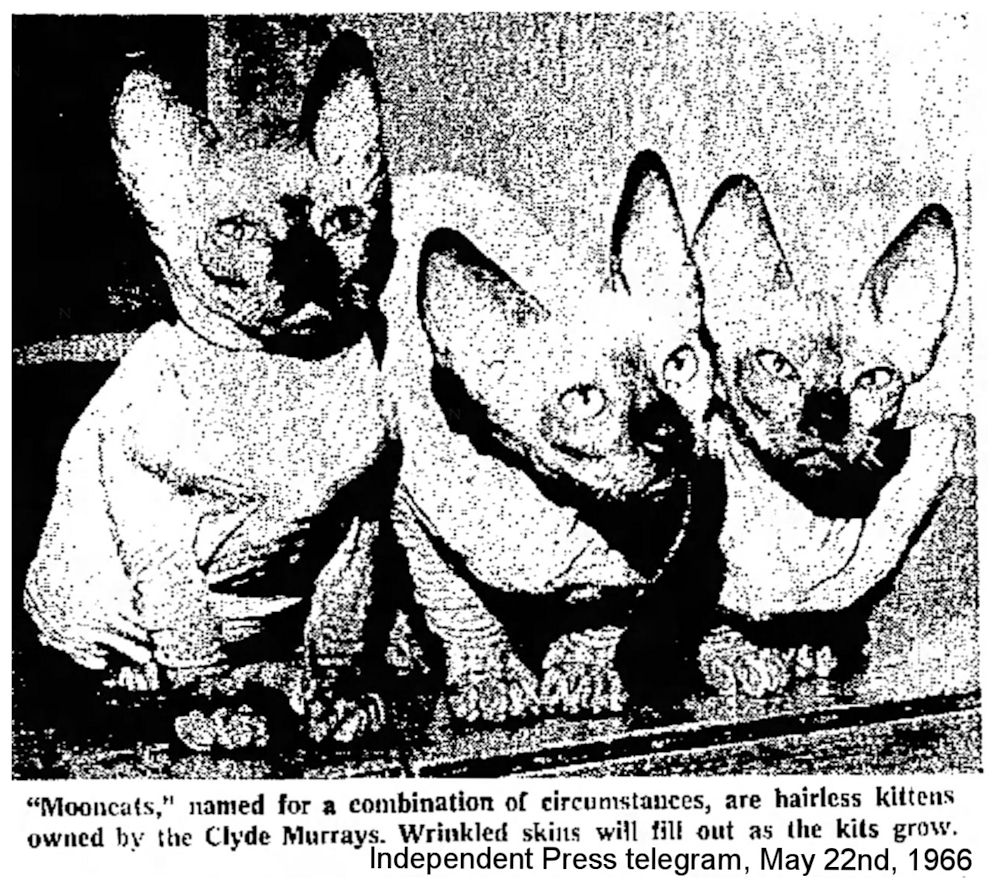

“Three Little Kittens Lost Their Mittens - and Fur Coats, Too. By Eleanor Avery Price, Independent Press Telegram, May 22nd, 1966. There are experimental breeders of cats who are fascinated with discovering and establishing something new in the way of felines. When the Rex cat first emerged in both Germany and England along about the same time, it was a cat covered with a fairly thick wavy coat. The cat’s build was somewhat like an ordinary shorthair. A picture of one of the early German Rex mutations appeared in the Journal of Genetics in 1956. It seems, however, that more was to come in the way of Rex mutations. A small slender cat with a slinky manner, big ears, and body somewhat similar to a Siamese cat appeared with a thin, very soft, wavy coat and almost no fur on the stomach. This cat, when shedding, is temporarily almost completely hairless. The first genotype was called Rex I, and the second Rex 2. They were brought to the attention of A. C. Jude who wrote articles in scientific and technical Journals on the behavior of genes in rabbits which produced various Rex coats. He had known that in 1920 a Rex coat appeared in rabbits of the breeding stock of a French peasant. After studying the Rex cats, he discussed them in his book, "Cat Genetics,” describing in detail the established action of cat genes. Rex cats have since appeared in the United States. And in recent months, a hairless Siamese appeared in this area. Obtained by Mr. and Mrs. Clyde Murray, Moonglow Cattery, Bellflower, the cat, a male, was named Silki. In time, he was bred to an ordinary Siamese, Suki. The litter of kittens is hairless and is pictured today with this article. The whiskers of the three little kittens, without so much as mittens, are stubby. The skin is wrinkled but will fill out just as does the skin of the Mexican xololtzcuintli dog. Otherwise, they are normal, playful and happy. The Murrays do not know if they have added Rex No. 3, an altogether hairless Rex, or if a completely new mutant gene has appeared. The hairless Siamese in body greatly resemble the Rex curly coated cats we see in cat shows. They have the whip tail, the big ears, the exotic head. There is possibly a great future for this fascinating oddity. Anyone with an allergic reaction to cat fur might find a hairless cat just the feline he or she can enjoy. And certainly some of the cat fancy will welcome a new character. Of course, no standards have been set, no breed name given the hairless Siamese except the humorous one (which might stick) given by Murray - Mooncats - because the felines are a bit weird and because the cattery now producing the rarity is named Moonglow. Murray says that it is rumored that at one time hairless cats existed in China and that it is also rumored that at one time there were cats in Mexico with just a bit of fur on the stomach and on the ridge of the back."

The modern Sphynx (Canadian Hairless) may be advertised as the hairless cat from the scrolls of antiquity, but it derives from Canadian cats of either the 1960s or 1970s. It has variously been known as the Moon Cat, Moonstone Cat or Canadian Hairless and may be spelled either Sphynx or Sphinx, though the former spelling is more common. The history of the Canadian Sphynx is not continuous as the original bloodline has been lost, but the breeding program was restored when more hairless kittens surfaced later. The later cats were probably related to the earlier discovery, but there is no traceability.

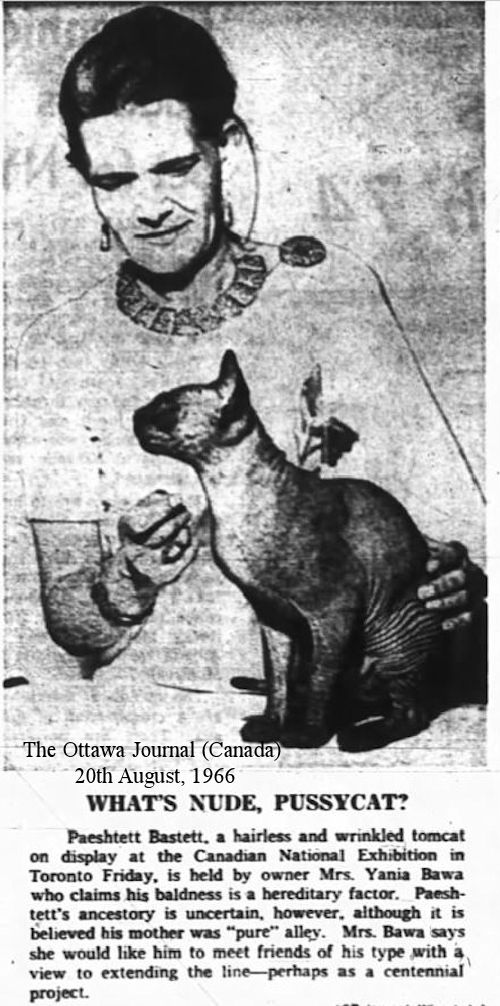

The Ottawa Journal (Canada) 20th August, 1966, under the title “WHAT’S NUDE, PUSSYCAT?” gives us this: Paeshtett Basiett, a hairless and wrinkled tomcat on display at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto Friday, is held by owner Mrs. Yania Bawa who claims his baldness is a hereditary factor. Paeshtett's ancestry is uncertain, however, although it is believed his mother was "pure"' alley. Mrs. Bawa says she would like him to meet friends of his type with a view to extending the line - perhaps as a centennial ’ project. [. . . ] Hairless cats for owners with allergies may soon be available, says Riyadh Bawa. owner of a hairless tomcat named Prune who is appearing at the Canadian National Exhibition this year. Bawa said in an interview today that chances are that Prune can make cat history by becoming "big daddy" to a new breed of hairless cats in the next five or six years. “Think what a boon that would be to cat levers with allergies.'' said the University of Toronto graduate student. “The cats must remain hairless for seven generations to be recognized as a breed.”

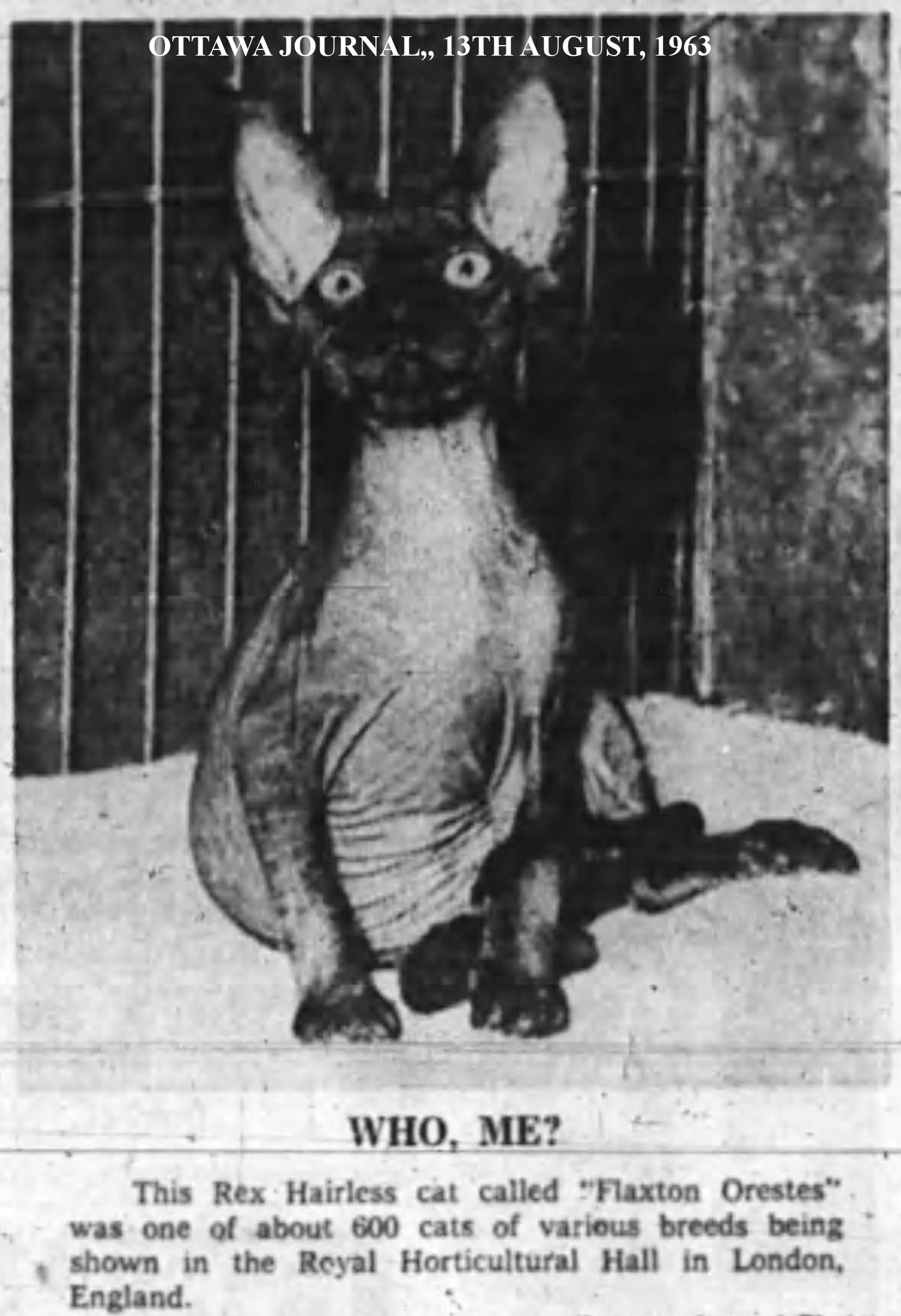

The Sphynx's recessive gene mutation appeared more than once in Toronto, Canada but the cats were most likely related. Hairless kittens were discovered in Toronto in 1963 and it was established that the trait was due to a recessive gene. They were bred, but the breeding experiment was discontinued in the late 1970s. Though a number of breeders were working with these cats, the breed was not eligible for registration and many small breeding programs were started up, only to vanish without trace a few years later. Inexperienced breeders produced unhealthy or poorly fertile cats, signs of inbreeding. In 1973, the Journal of Heredity ran a report on these hairless cats. In 1978, the last breeding pair of cats from that breeding program went to Holland. The cats were brother and sister and though the female produced a litter of kittens, she rejected them. They did not manage to produce any further kittens which suggests poor fertility/infertility due to severe inbreeding. What was needed, were further female Sphynxes to widen the gene pool.

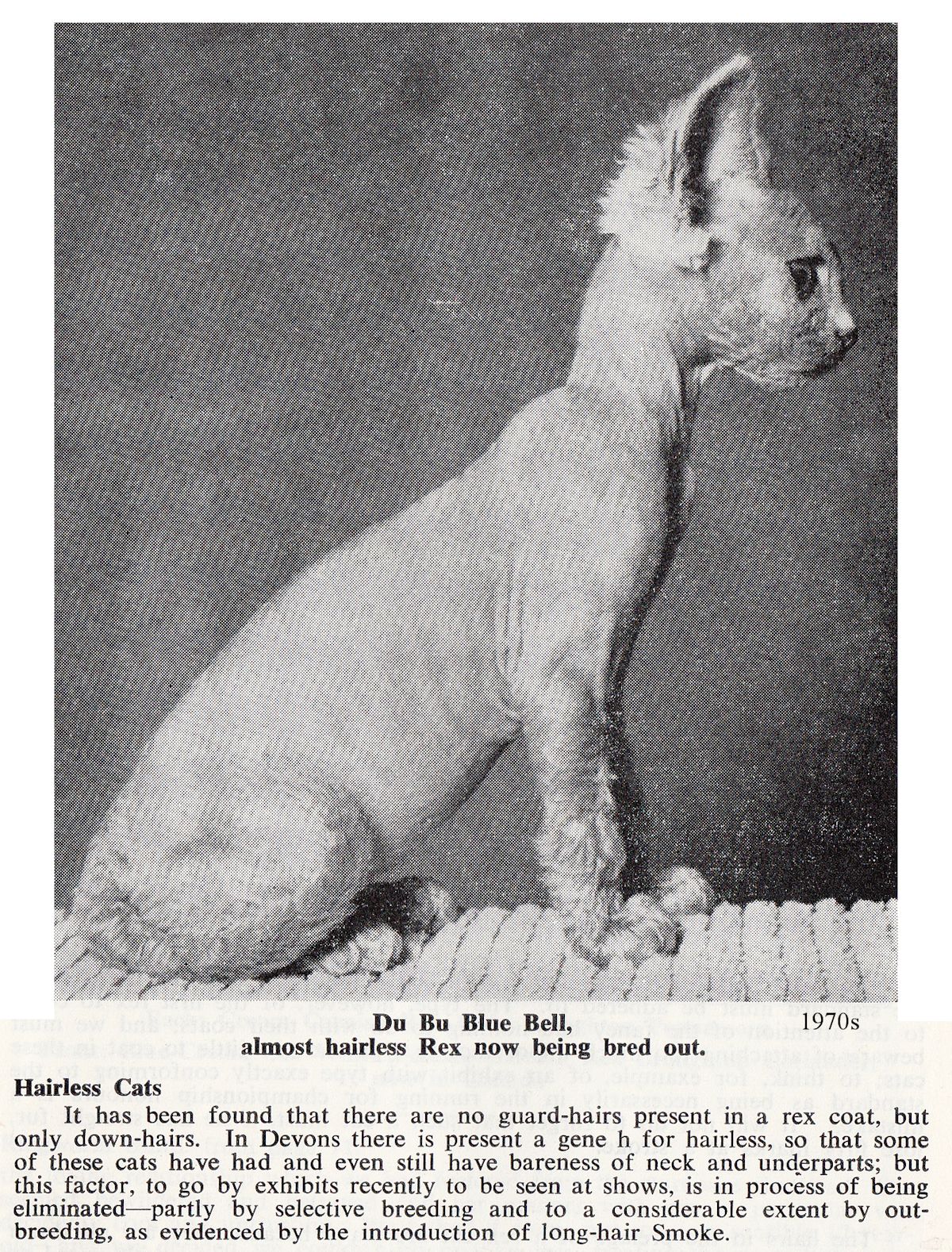

Coincidentally, also in 1978 (some reports erroneously state 1973, probably based on the report in the Journal of Heredity relating to the earlier hairless cats), a litter with hairless kittens was discovered among street cats in Toronto. The mother giving birth to two further hairless female kittens in separate litters in 1980. Since the gene for hairlessness is recessive, both the mother and the two sires must have carried the gene. It is likely that the parents of those kittens were unrecorded progeny from the earlier, failed, breeding program. The two 1980s females were sent to the Netherlands to the same person who held the last of the 1970s strain. He attempted to breed the two strains together. The male refused to accept either of the two new females and was neutered. It was discovered that one of the females was pregnant by that sire, but she lost the litter and with it the genes of the last authenticated Canadian Hairless of the earlier strain. The Sphynx breed was therefore developed using Devon Rex. Devon Rex sometimes occur with sparse fur and in 2010 DNA analysis found that Devon Rex and Sphynx are alleles of the same gene. Rather than being totally hairless, the modern Sphynx derived from Canadian cats and other genetically compatible spontaneously occurring hairless cats has a light peach-fuzz on the skin and sometimes fur on the tail-tip. Unlike the Mexican Hairless, it does not grow a ridge of fur during the colder seasons.

A further Canadian Sphynx appeared during the early years of the breed; this being a hairless male farm cat found in Western Canada. Though acquired by a Sphynx owner in Washington state, he does not appear to have contributed to the modern Sphynx line. Possibly he was genetically incompatible or otherwise unsuitable.

In 1970, two nude cats (later named Starkers and Baldy) were cared for at the Blue Cross Animal Hospital in London's Victoria district. The pair appeared in the Daily Mirror newspaper apparently in spite of its "no nudes" policy! In 1975 and 1976, Jezabelle, a tabby shorthair farm cat owned by Minnesota couple, Milt & Ethelyn Pearson, had given birth to two hairless female kittens - Epidermis (1975) and Dermis (1976). These were later used to expand the Sphynx gene pool. The Pearsons' farm cats bred freely and there were hairless kittens born in several litters, suggesting a mutation several generations earlier followed by a degree of inbreeding. A hairless male barn cat occurred in North Carolina, but there are no recorded offspring from this cat.

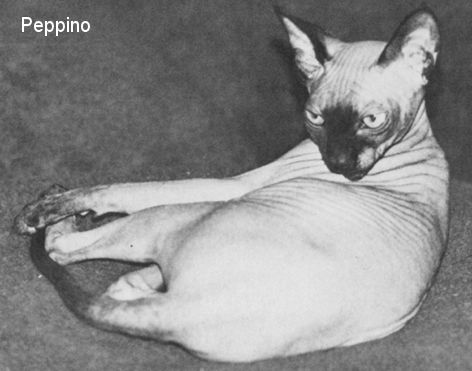

Peppino was a spontaneous hairless cat reported in 1982. She was born to a friendly pregnant stray cat that had four kittens - three black with white bibs and feet, but the fourth kitten was hairless and so much smaller than her littermates that it was initially assumed she was premature and unlikely to survive. Peppino survived, but being the runt needed human help. At two months old she grew some fuzz on her face, lower legs, feet and tail and looked like a small, grey Siamese, except that the grey was grey skin, not fur.

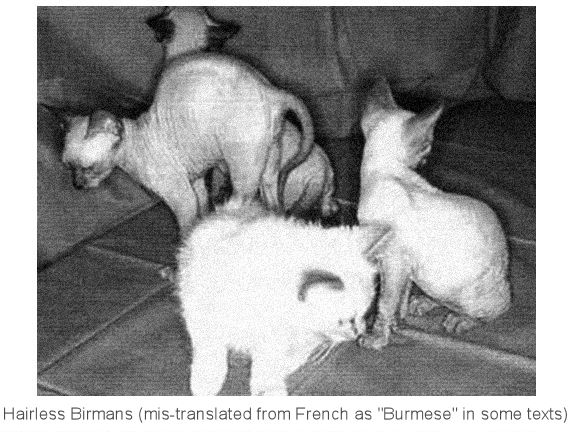

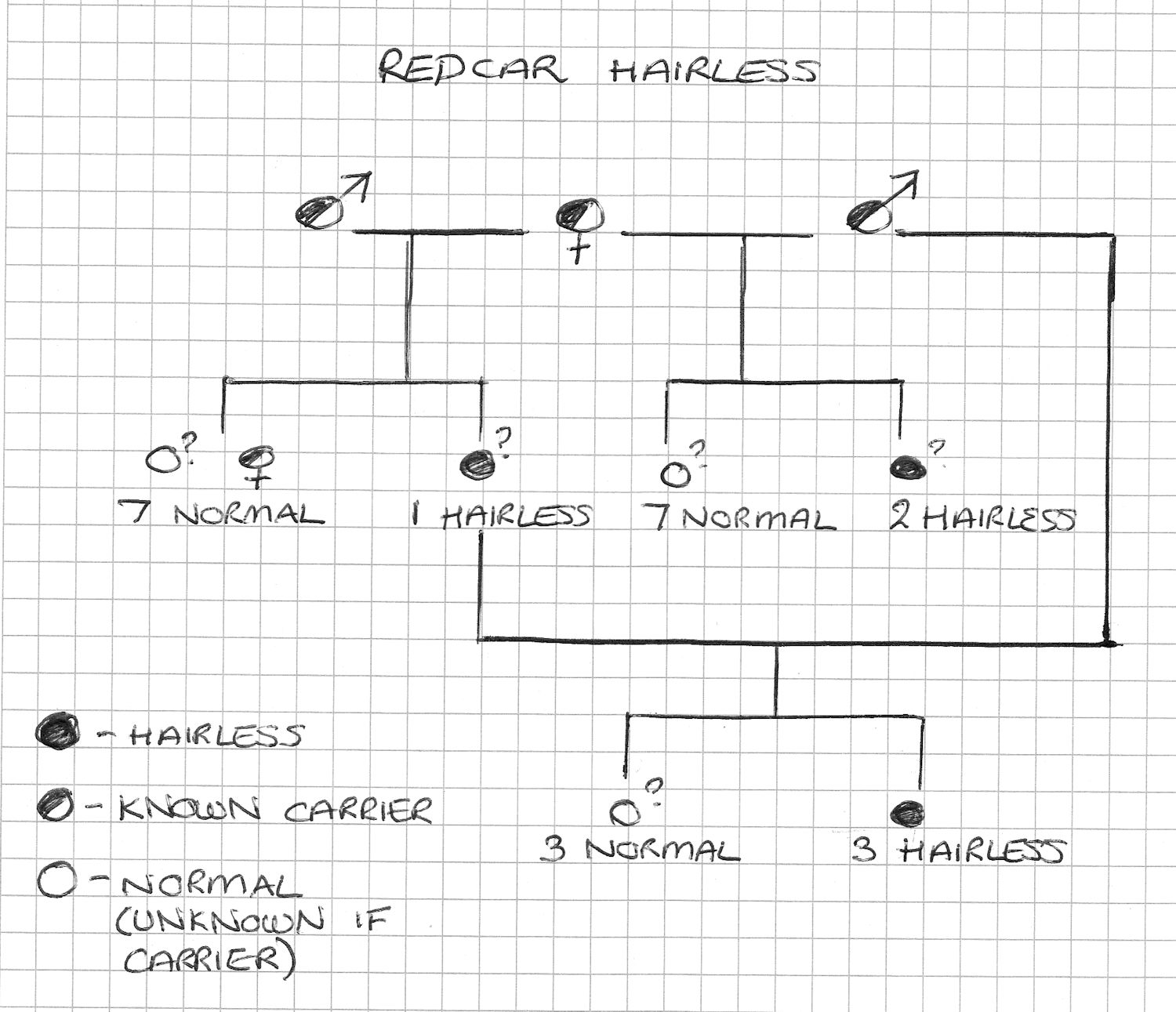

In 1984, the Journal of Heredity reported hairlessness in 10 Birman kittens born in England between 1978-1982. The hairless Birman kittens had short or absent whiskers and greasy skin. None survived beyond ten weeks of age, dying from various disease processes (possibly a metabolic or immune system disorder). This type of hairlessness was already associated with a lethal gene following a study in 1981. The hairless kittens were observed by a breeder in 1977 in Redcar, Cleveland, UK in litters of pedigree Birmans with no previous history of hairlessness in the pedigrees. The stud was somewhat inbred, but this was not unusual for the breed. The female was mated to 2 different, but related males. The first stud fathered 7 normal and 1 hairless kitten. The second stud fathered 7 normal and 2 hairless kittens. A normal-furred female from the first pairing was mated to the second male and produced 3 normal and 3 hairless kittens. The 17 normal and 6 hairless kittens was consistent with a recessive mutation. When mated to an unrelated Siamese male, the original female Birman produced normal kittens. The condition was lethal with death usually occurring before 2 weeks of age. Affected kittens never grow more than a fine coating of down. Based on the longest surviving cat (a male, died aged 3 months), the skin is soft at birth but steadily becomes thickened and wrinkled. The few whiskers present are short, thin and crinkled. In the kittens that died before 2 weeks, there was also a brownish secretion accumulating around the nostrils and eyes, and under the chin (believed to be a secondary bacterial infection). A male Redcar hairless that survived to 3 months had defective, easily split claws. It died suddenly of no obvious cause, but had suffered persistent diarrhoea since weaning. This male had been completely hairless from birth apart from a few short, bent whiskers.

In 1986 (unconfirmed date) a hairless cat turned up at a New York, USA animal show. The owner claimed to know of a hundred more in various locations around the world. In 1986 a hairless female was discovered in a colony of freely breeding domestic shorthairs in Bloomfield, New Jersey, but the owner apparently would not allow this cat or its normal haired offspring (which would carry the gene for hairlessness) to be used in the Sphynx breeding program. In 1993, a mother cat with three normal-coated kittens and one hairless kitten was rescued in Westchester County, New York. The kitten, known as Gracie, proved to have a different mutation. She produced normal coated offspring when mated with a Sphynx. In 1995 a hairless male kitten was born to two long-haired parents in Tennessee and was incorporated into the Sphynx genepool. A hairless male from the White Mountains of Arizona was added to the Sphynx gene pool (date unknown).

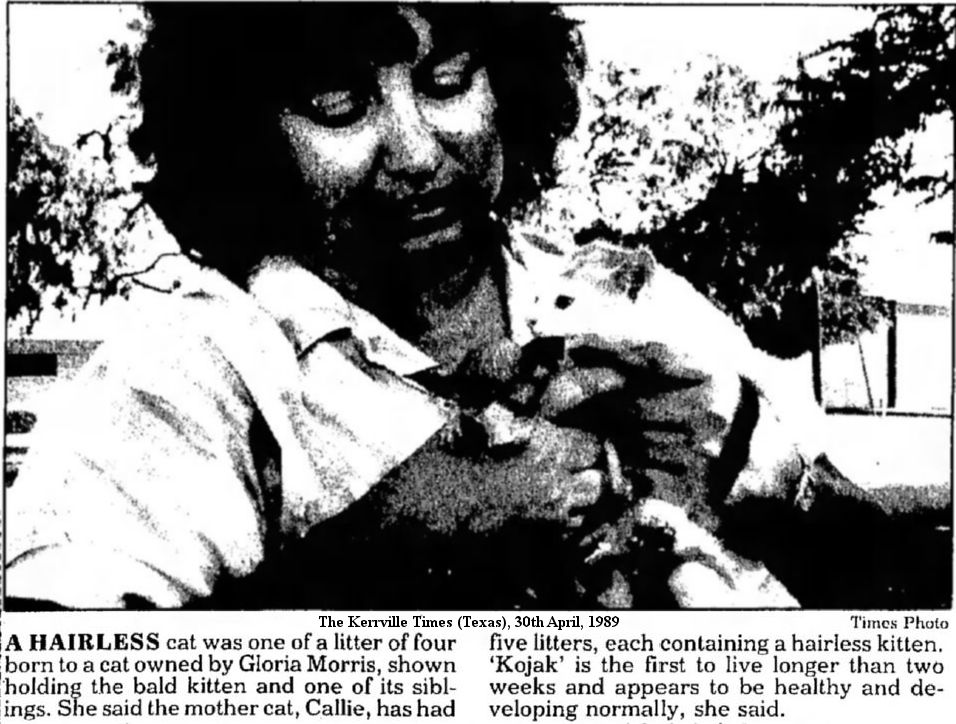

The Kerrville Times (Texas), 30th April, 1989 - A HAIRLESS cat was one of a litter of four born to a cat owned by Gloria Morris, shown holding the bald kitten and one of its siblings. She said the mother cat, Callie, has had five litters, each containing a hairless kitten. ‘Kojak’ is the first to live longer than two weeks and appears to be healthy and developing normally, she said.

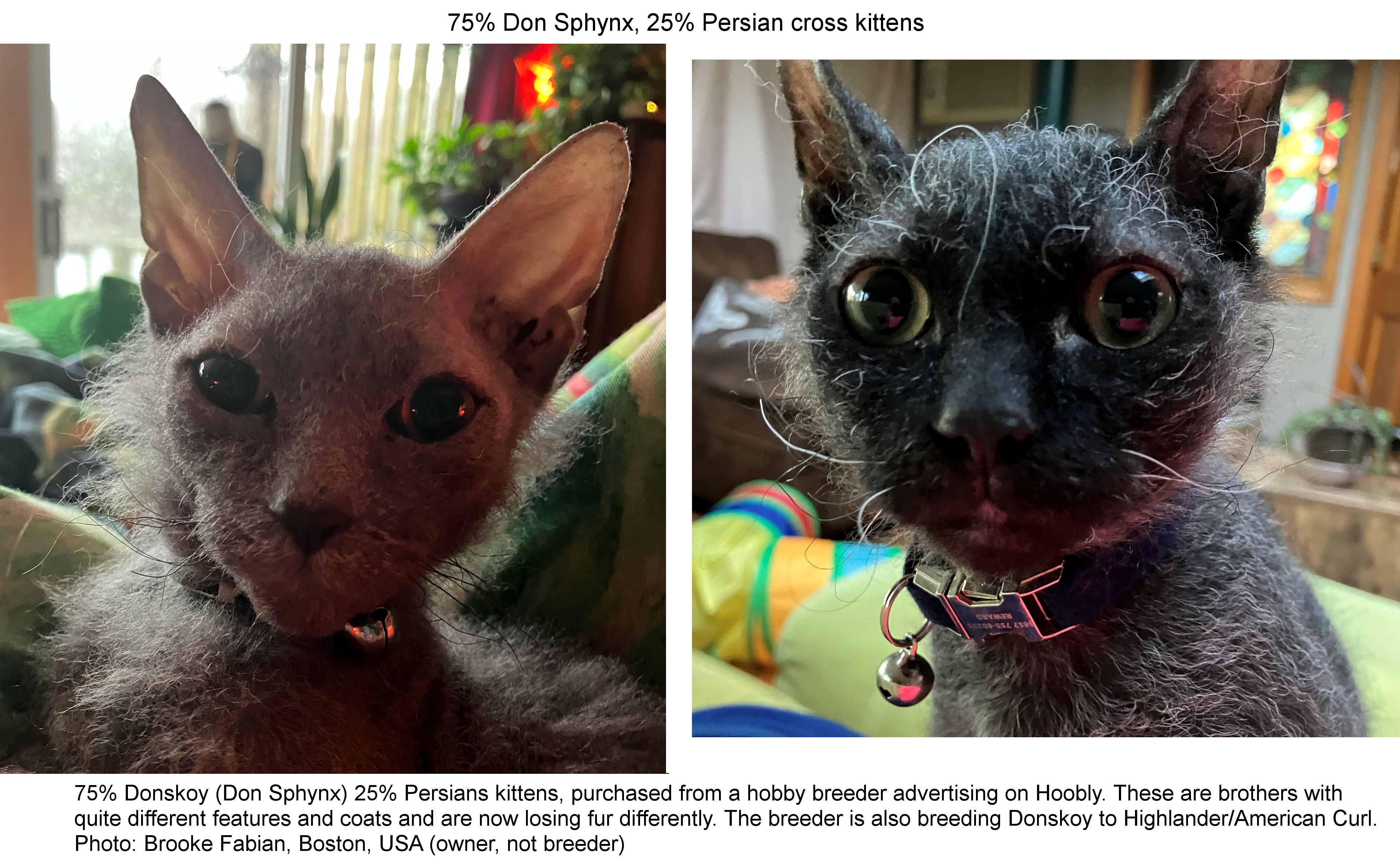

Hairlessness has also occurred in Persian cats, a breed known for its long fur. In Persians, hairlessness was considered shameful; the existence of hairless kittens was therefore a closely guarded secret among those working with the affecting breeding line so that carriers could be eliminated from the Persian breed. Mutating genes have no respect for which breed they turn up in! Below are shown 2 hairless Persian kittens and an unusually short-faced Sphynx for comparison; note the wrinkling of the SPhynx's skin around the eyes and muzzle compared to the less wrinkled blad Persian kittens.

In 2004, the Cheops was apparently derived from Canadian lines of the American Cornish Rex. It has a very fine coat, approximately 1/8" long over the head, neck, back and sides and a slightly longer coat on the chest and hips, however this residual coat lacks the waviness of the Cornish Rex. The tail may have a tuft at the tip.

The Elf breed was initiated in 2006 with the first full hairless, curl-eared Elf being born in 2008. It combines the Sphynx hairlessness with the American Curl's ear conformation. Permissible out-crosses include non-pedigree domestic shorthairs. They have a sturdy, athletic build, are sociable, intelligent, inquisitive and people centred. Half-Elf cats e.g. furred Elf variants result from outcrosses to diversify the gene pool. A short-legged version calledthe Dwelf also exists.

Throughout the world there are still reports of hairless kittens appearing in litters of feral cats and house cats. Hairless cats found in domestic cat litters may still be used in the Sphynx breeding programme to strengthen and expand the gene pool. Some of them are producing extremely hairless offspring, suggesting that several genes may be involved, not just a single simple mutation. Others, like the much more recent Peterbald (discussed later), prove incompatible with the Canadian Sphynx because they have a different mutation. In the USA, hairless cats have been found in North Carolina, Minnesota, Texas, Arkansas and Indiana. In Canada they have turned up in Toronto and in Western Canada (no precise location given). They have also occurred around the world although to date only the Canadian, Russian and Hawaiian mutations have given rise to distinct breeds.

RUSSIAN HAIRLESS CATS

for many years, the Canadian-bred Sphynx was unopposed as the sole hairless cat breed. This changed with the appearance of the Don Sphynx (Don Hairless, Russian Hairless, Don Bald Cat, Donskoy/Donsky) in 1987. Donskoy Sphynx originated in the small town of Rostov-on-Don in Russia. The foundation female of the Donskoy Sphynx and the related Peterbald was a blue tortoiseshell cat named Varya, who was rescued by Elena Kovalyova. At the time it was thought that hairless Varya had lost her fur through illness, but in pite of anti-fungal treatment the fur did not grow and Varya proved to be in good health. Around 1989, Varya was bred to a neighbouring tomcat and produced several hairless kittens. One of those kittens, a black female called Chita, went to Irina Nemykina's "Myth" cattery. Nemykina's records showed that the mutation was dominant. The hairless cats in the Myth aattery were bred to European Shorthairs and Domestic Shorthairs and these became the foundation cats of the Donskoy Sphynx breed.

Matings of the Donskoy cats with Oriental/Siamese in St.Petersburg and Moscow in 1993 created an oriental type of hairless cat known as the Peterbald. Though unpopular in Moscow, they were popular with St.Petersburg breeders. The first Peterbalds were born in January of 1994 from a mating between an Oriental tortoiseshell female called Radma von Jagerhof with a brown mackerel tabby Donskoy Sphynx male called Afinogen Myth. Afinogen Myth had a light bone structure and a wedge-shaped head, making him a good choice for breeding with Oriental cats. He was also mated with Russian Blues, producing Donskoy Sphynx. Some of the more elegant kittens from the Afinogen Myth x Russian Blue matings were incorporated into the Peterbald breeding programme and became foundation cats.

The Russian standard for the Donskoy Sphynx requires solid, medium size cats with a short, wedge shaped head, large ears, noticeable eyeballs and a flat forehead with numerous vertical wrinkles spreading in horizontal lines above the eyes. The whiskers range from thick and curly to snapped or absent. The toes are unusually long in appearance. The last 3 centimetres of the tail tip may be covered with soft, dense, close lying, slightly curly coat. The skin is describes as elastic and wrinkled on the head, neck, under the legs and in the groin. Young cats (under 2 years old) may have short fur on the muzzle, cheeks and at the base of the ears and in the winter, the whole body may be covered with a fine coat. Donskoy Sphynx kittens may be born with wavy rex coats and a bald spot on the head, but the required distinctive sign of a newborn Donskoy are curly whiskers.

The heterozygous offspring of matings between the Donskoy Sphynx and a furred outcross can be variable in appearance: some heterozygous offspring have a residual curly coat at birth and this varied from short velvet to unusually fine normal length hair. Generally there is a bald spot on the crown of the head. As the heterozygous kittens mature, the hair follicles died except for those at the points. These furred kittens shed their coats between 2 months and 2 years of age. Other heterozygous kittens have thick curly (rex) hair and remain coated throughout their life; these variants are known as "brush". The mutation also affected the conformation and most "brush" variants lack breed's characteristic short wedge face. In the second generation (i.e. shed x shed or shed x brush) a third type appeared: completely hairless at birth, wrinkle-skinned and often without whiskers. The hairless and velvet Donskoy Sphynx tend to grow more slowly than their furred siblings.

The relationship between these mutations from most dominant to most recessive is: Russian Hairless >> Normal Hair >> Sphynx >> Devon Rex. Test matings show that thee are predictable factors(modifiers) dictaitng the different coat types.

Hrbd (bald) - Russian Hairless Gene Dominant

- hi – mInimiser modifier for Improving hairlessness

- ha – mAximiser modifier for constraining/weakening hairlessness

Hr – normal haired

Combinations:

HrHr + hiha = normal haired (this could have any combination of modifiers because they only work on the Hairless-Bald gene)

HrbdHr + hihi = brush coat

HrbdHr + hiha = brush coat with some bald areas

HrbdHr + haha = brush coat that turns bald

HrbdHrbd + hihi = velour coat

HrbdHrbd + hiha = flocked coat

HrbdHrbd + haha = rubber bald – born bald and remains bald

The Donskoy Sphynx is now being seriously bred in the USA and its breeder suggested using it to found an experimental Hemingway Sphynx (or Dossow Cat) which would be a variety of hairless cat with extra toes.

In 2005, the Ukrainian Levkoy Cat, a fold-eared naked cat, was created using the Don Sphinx and Scottish Fold. The Ukrainian Levkoy is less extreme in body and face type than the Don Sphinx (the face is wider and ronder) and the ears do not fold tightly to the skull as in the Scottish Fold, but stand out from the head and fold closer to the tips. It also occurs in velour and pric-eared forms.

The Peterbald (St Petersburg Hairless) is another Sphynx-like Russian breed derived from the same female, but with an oriental-type body. It originated as cross between Don Sphynx and Oriental-type household pets in St Petersburg. Some matings of Don Sphynx to Oriental/Siamese occurred in St.Petersburg and in Moscow in 1993. The first true Peterbalds were born in January 1994 using a tortie oriental female and tabby Don Sphynx with some Oriental traits. The Don Sphynx was also bred with Russian Blues to produce more Don Sphynx, but some of these offspring were used in the Peterbald breeding program. Like the Don Sphynx, the Peterbald is now also bred in the USA. If a Peterbald (or Don Sphynx) is crossed with a Sphynx, normal-coated kittens result because the hairlessness is caused by different genes.

A rexed Peterbald Longhair was produced from a very early Russian import mated to an Oriental Longhair. Both Cornish and Devon Rexes were used with early Oriental Shorthairs and it’s likely that rexes, or Rex carriers, were used in Russia as part of the early Peterbald breeding program.

RECENT HAIRLESS CAT DEVELOPMENTS

Hairless cats still pop up out of nowhere due to mutation or hidden recessives inherited generations back. Many are treated as oddities and are neutered because the trait is seen as detrimental. Elsewhere, the new occurrences may either be used to expand the gene pool of an existing hairless breed (if found to be genetically compatible) or used to create a whole new breed (if genetically different).

In 2002, the Hawaiian Hairless (or Kohana Kat) was reported. These cats were claimed to be the only completely hairless cats, since they lacked hair follicles and had a skin texture like rubber. The Hawaiian Hairless originated from a feral litter in Hawaii, and were allegedly due to a gene that masked out the dominant gene for full-coatedness. Unlike the other hairless breeds where the mutation affects the function of the hair follicles, this mutation allegedly caused the complete absence of hair follicles. There were other, unconfirmed, reports that it was the result of mating a Donskoy Sphynx to a Canadian Sphynx and the interaction of the 2 different genes. In 2010 it was confirmed by DNA analysis that the Kohana Kat had the same hairlessness mutation as the Sphynx, with other effects being due to other genes in the mix, and it was not a new mutation, but was a variation of an existing mutation. By this time the Kohana Kat had all but died out due to reproductive problems and other health issues that may have been due to inbreeding.

DNA analysis in 2010 also found that Sphynx and Devon Rex are different mutations of the same gene. The relationship between these mutations from most dominant to most recessive is: Normal Hair >> Sphynx >> Devon Rex

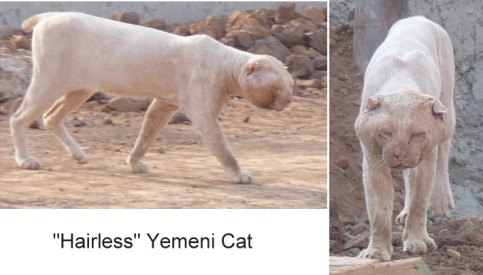

This is a hairless stray/feral domestic cat photographed in south-eastern Yemen where it was loitering on a building site and apparently chewing cable (a condition known as pica that is more common in Siamese/Burmese cats). It has a peach-fuzz of fur, with more fur on the extremities, suggesting a hairless mutation. The little colour visible (on the tail and near one ear) indicate it is ginger-and-white. The battle-scarred ears indicate a cat that has been in frequent fights; the puffiness of the face indicates a serious infection or tumours and the lack of fur/pale colour generally puts the cat at risk of skin cancer. The shortened tail could be a natural and relatively common bobtail mutation or the result of an injury. The puffiness around the eyes indicate further problems and the skin appears thickened which may be due to chronic mange or infection. All in all, the cat is in a sorry state.

HAIRLESS BIRMANS – A GENETIC STUDY

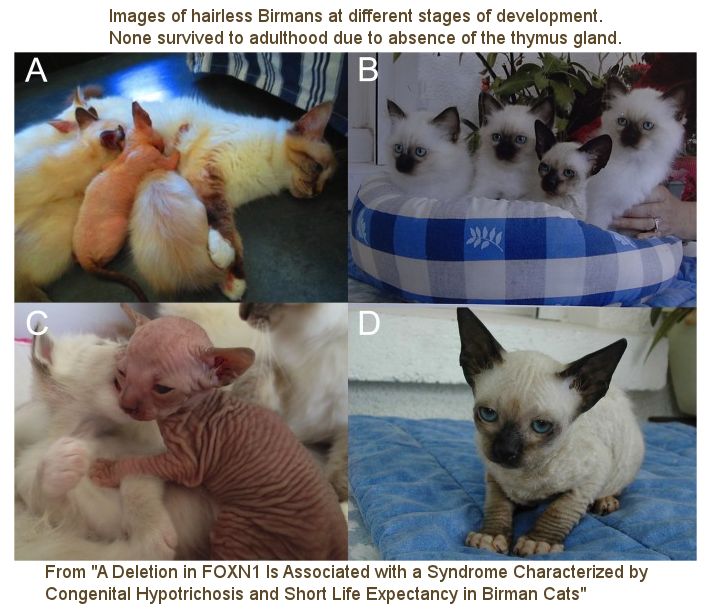

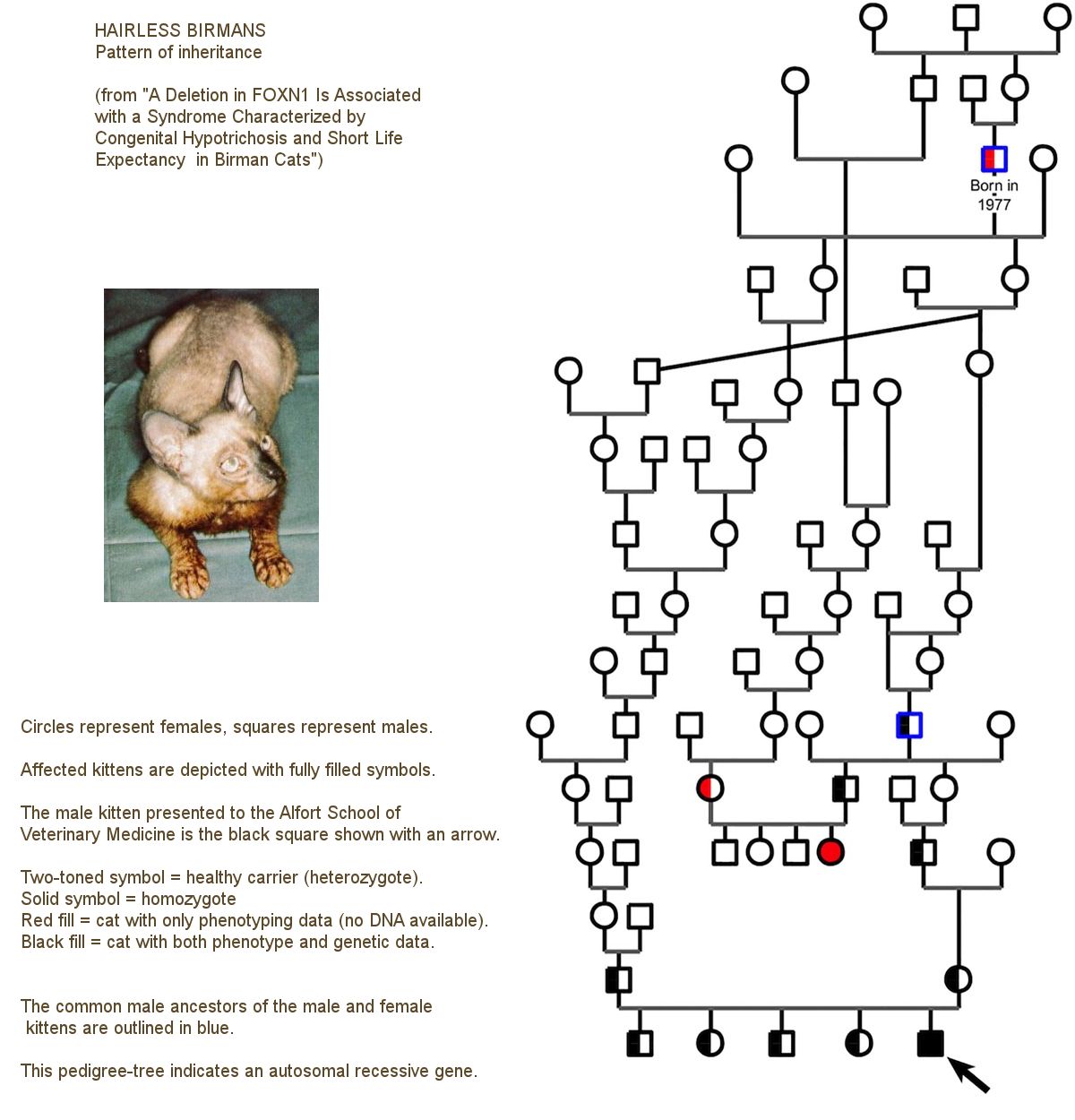

A summary of “A Deletion in FOXN1 Is Associated with a Syndrome Characterized by Congenital Hypotrichosis and Short Life Expectancy in Birman Cats” by Marie Abitbol, Philippe Bossé, Anne Thomas and Laurent Tiret)

Sphynx cats are homozygous for an autosomal recessive hairless allele (hr or Canadian hairless) of the KRT71 (keratin 71) gene. Donskoy and Peterbald breeds carry a semi-dominant hairless mutation, not yet identified. A deferred lethal gene has now been identified in Birman cats.

An autosomal recessive syndrome characterized by congenital hypotrichosis and short life expectancy has been identified in the Birman cat breed. The percentage of healthy carriers in surveyed Birmans in France was estimated to be 3.2%. The mutation truncates a protein needed for normal hair and for thymus gland epithelial development. . A similar syndrome had been reported in hairless mice about 50 years earlier. The FOXN1 protein of cats and mice is very similar. A DNA test is available to help owners identify carriers of this lethal gene.

In Birmans congenital hypotrichosis associated with reduced lifespan was described during the 1980s, with hairless kittens born to two purebred Birmans in France and the UK. The 13 reported hairless kittens died (or were euthanized) within 8 months. Many exhibited respiratory or digestive infections (resulting in chronic diarrhoea), or for unexplained medical reasons.

[Supplementary Information: In 1978, Peter Hendy-Ibbs described a hairless kitten, with 3 furred siblings, in British Birmans. The stud was somewhat inbred , which was not unusual for the breed. 9 hairless Birmans kittens were born from the same lineage in the following 4 years, bringing the number of hairless kittens to 10 out of 25 kittens. A study in 1981 found that it was a lethal recessive mutation. In 1984, the Journal of Heredity carried a report on the 10 hairless Birman kittens born in Redcar, Cleveland, England between 1978-1982. None survived beyond 10 weeks old, most dying before 2 weeks old. The mother was mated to 2 related males. Stud A fathered 7 normal and 1 hairless kitten. Stud B fathered 7 normal and 2 hairless kittens. A normal-furred female from Stud A was mated to Stud B and produced 3 normal and 3 hairless kittens. The ratio of 17 normal and 6 hairless kittens was consistent with a recessive gene. They never grow more than a fine coating of down on the upper parts. Based on a male that died at 3 months (the oldest survivor), the skin was soft at birth but became thickened and wrinkled. The few whiskers present were short, thin and crinkled. The claws were defective and easily split. In the kittens that died before 2 weeks, there was a brownish secretion around the nostrils and eyes, and under the chin, possibly due to bacterial infection. They also developed a strong smell and needed regular washing.

In 1986 in France and then in 1994 in Switzerland, further hairless Birmans were born and were studied at the Alfort School of Veterinary Medicine, France. ]

Post mortem examination of 9 hairless Birman kittens born to two normal parents in Switzerland revealed the thymus was absent, and there was lymphocyte depletion in the spleen and lymph nodes. The pedigrees indicated an autosomal recessive inheritance for this syndrome that combines congenital hypotrichosis and thymic aplasia (thymus fails to form).

In 2013, a male kitten was presented to the Genetic Consultation at the Alfort School of Veterinary Medicine, France. He was the only hairless kitten in a litter of five born to two normal Birman parents. A cheek swab was taken for DNA study. This male died at home at four months of age, from severe diarrhoea, probably due to infection. His pedigree revealed that his mother was related to a Birman male known to have sired a hairless female in 2004. That female was euthanized at seven months due to repeated skin infections, but no tissue or DNA samples were taken. Both kittens were born hairless and developed sparse, shortened and fragile fur. Their skin was wrinkled and greasy-looking. Initially, they were as active as their littermates and grew normally. The kittens shared a common ancestor born in 1977, and now known to have produced several hairless kittens.

DNA swabs found that the male kitten’s sire, dam, maternal grandfather and four normal littermates all carried the mutation. The father and paternal grandfather of the female (born in 2004) were heterozygotes for the mutation. A wider study of 215 non-Birman pedigree cats found no cat carrying the mutation. Out of 126 French Birman cats, excluding first-degree relatives, 3.2% apparently normal cats carried the mutation.

Birman cats were developed in France at the beginning of the 20th century by crossing “gloved Siamese cats” with Persian cats. It was recognised as a breed (which limited further outcrossing) in 1925. DNA samples from 16 Siamese/Oriental short/longhaired and 29 Persian/Exotic cats found none with the mutation. The authors were not aware of any hairless Persian cats [it has been seen in a Persian litter, but not studied]. Hairlessness has been documented in the Siamese breed, but was not associated with reduced lifespan and the hairless Siamese cats were able to breed. This indicates a different mutation from the one found in Birmans. The two affected kittens and the nine healthy carriers from the family being studied, plus additional hairless Birman kittens, were all related to a Birman stud born in 1977. This means that the Birman FOXN1 mutation occurred in the Birman gene pool between the 1920's and before 1977.

Two hundred and sixty four cats from 16 breeds were included in the French study. Cheek swabs were taken from these between February 2010 to March 2014 and included individuals from the following breeds: 49 Birman (including the presented male and 9 of his relatives), 29 Persian, 21 Chartreux), 20 Sphynx, 20 British shorthair and longhair, 20 Norwegian Forest, 16 Siamese/Oriental shorthair and longhair, 15 Maine Coon, 15 Abyssinian/Somali, 14 Ragdoll, 13 Bengal, 11 Domestic shorthair/longhair, 10 Devon Rex, 6 Siberian, 4 Russian/Nebelung, and 1 Bombay.

The researchers were unaware of any hairlessness in the Persian (I am aware of at least one case, but this is anecdotal). Hairlessness has been reported in the Siamese, but was not associated with reduced lifespan and the affected cats were able to breed. All affected Birman kittens were related to a Birman male born in 1977, therefore the Birman FOXN1 mutation arose after the creation of the breed in the 1920's and before 1977.

Cheek swab DNA samples from 87 additional Birman cats, previously collected for DNA identification purposes, were used as controls. All cats were client-owned cats so there were no invasive procedures. However, the downside of this study is that the cats are considered a suitable animal model for experimentation, replacing pigs. It seems unlikely that Birman breeders of affected would release animals for experimentation. Their shortened lifespan is also a problem.

FUTURE HAIRLESS?

Potentially, any of the hairless breeds could be crossed with any other breed of cat to produce hairless cats with bobtails, no tails, extra toes, different ear shapes, different body conformations (e.g. the stocky conformation of the Persian) and other combinations of physical traits. Whether these are desirable is another matter entirely and many experimental cross-breedings are not pursued as breeds. In 2006, TICA's Genetics Committee proposed to clamp down on the trend of mix-and-match breeding.

HAIRLESS CATS IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING