THE GREAT AUSTRALIAN CAT PREDICAMENT

This article is a sequel to

The Great Australian Cat Dilemma and contains additional information and a far greater level of detail on feral cats, their habits and control. Additional information on the success of various feral cat control methods can be found in Why Feral Eradication Won't Work. I am indebted to a number of personal correspondents who have contributed their personal experiences and local information.

No-one is quite certain how many cats there are in Australia. The area is too large for a comprehensive head count and estimates vary wildly because some areas have more cats than others. Some estimates say there are 3 million pet cats and 5.6 million feral cats in Australia. A 1992 survey estimated 12 million feral cats and 18 million domestic cats (see also Declining Cat Ownership In Australia) . Without knowing how many cats there are, it is impossible to know how much, or how little, damage they do. What is certain though, is that in recent years these have given cause for concern over wildlife issues and the Australian Cat Issue has been discussed as a Parliamentary issue, and feral control and eradication programs have been funded and cat ownership curtailed or controlled by legislation.

Australia has 26 or more naturalized introduced (exotic) mammal species. "Wild" populations descended from domestic animals are called feral animals. Many introduced species are termed introduced pests, due to their impact on native species and the environment. The impact of these introduced species is of increasing concern. Some of the worst damage has been done by introduced species not termed pests: humans and livestock. Animals which did not evolve in the Australian environment do not fit into the natural ecosystem. Many native species evolved without the presence of major predators, so efficient introduced predators have had a significant effect on native creatures. Populations of introduced animals attain high numbers through lack of natural control influences and plenty of available prey.

A feral cat is defined as one which is not dependent on humans for shelter or food (except as a scavenger and opportunist). Cats exist in various states of domestication and dependence on humans. There is a continuum between feral and pet: semi-domesticated (semi-feral) cats, farm cats, urban ferals which are partly dependent on humans, stray cats which are unowned but not feral, roaming domestic cats, fully confined domestic cats. For convenience, cats are generally divided into two categories: unowned (tame strays + wild ferals) and owned (identifiable pets). Feral cats are considered a pest species because of their deleterious effect on native species. However feral cats, and cats in general, are also used as scapegoats for human activities which have had drastic effects on wildlife.

In this article, reference is necessarily made to feral cats in other countries (primarily the UK and USA) where the lifestyle and behavior of ferals has been more closely studied.

INTRODUCTION OF CATS INTO AUSTRALIA

The accepted view is that cats were introduced to Australia 200 years ago by European settlers. Cats first arrived with 17th Century Dutch shipwrecks and with Macassan traders. Cats were already present in parts of Australia not reached by Europeans during the early settlement of the continent. The cat was already known to Aborigines before European settlers arrived. Fossil records, distribution factors and DNA analysis of feral cats indicate that cats first appeared in Australia about 500 years ago. Aboriginals regard the cat as a traditional and significant food source. Some even have the Cat as a totem spirit and there is a "Cat Dreaming". European settlers facilitated the spread of cats and by the 1850s feral cat colonies were well established in the wild.

In "The Book of the Cat" (1903) edited by Frances Simpson, contributor H C Brooke wrote "There are, of course, no cats indigenous to Australia. An American writer gives it as his opinion that a certain strain of Australian cats is derived from imported Siamese cats. A specimen we possessed last year, which was born on a ship during the passage from Australia, and which exactly resembled its dam, certainly had every appearance of being of Eastern origin. It had the marten-shaped head, and a triple kink in the tail; its voice also resembled that of the Siamese. In colour it was grey with dark spots."

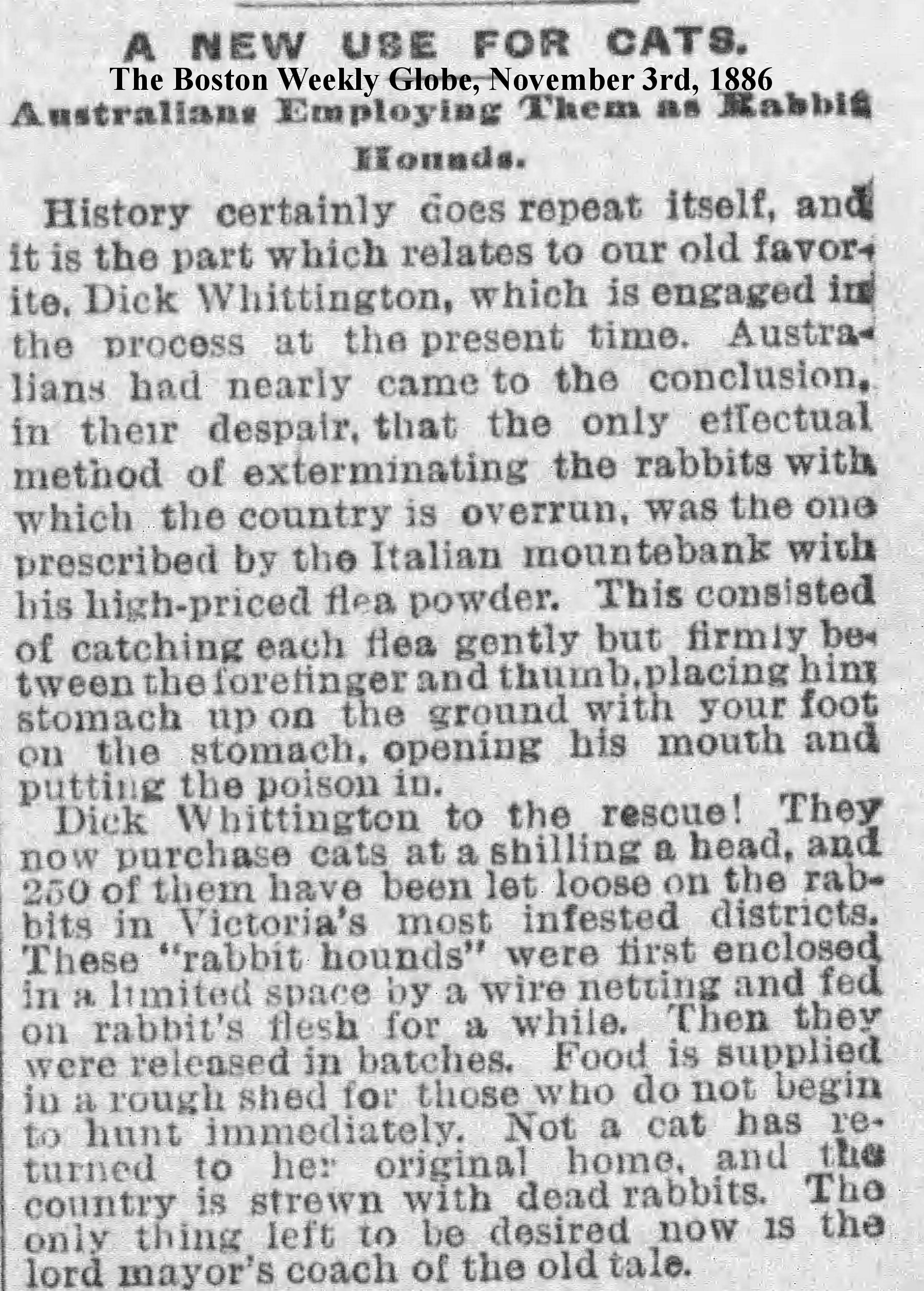

In the 1890s, feral cats were already widespread and (a something that current governments would prefer to forget) further cats were deliberately released into the wild to control introduced rabbits, but without any consideration for what the cats would do when the rabbits were gone - or the fact taht cats would find much easier prey among the naive native fauna. 200 cats were released between Eyre Patch and Mt Ragged in 1899 to control rabbits. 20 cats in breeding condition were released on Carnac Island in 1890-91 for the same reason. A further 30 were to have been released 12 months later, but, in 1892 it was reported that they had destroyed the rabbits. In 1901, 160 cats had been released in rabbit infested country. These are just a few examples. By 1903 there were reports that feral cats were becoming as great a plague as the dingo (semi-wild dog). By 1921 feral cats were declared vermin. In less than 25 years they had gone from being deliberately released beneficial predators to being vermin in their own right, indicating the foolhardiness of meddling with an ecosystem.

Cat populations thrived around rivers, creeks and the watering points at cattle stations. As the huge cattle stations were split into smaller properties, the number of watering points and homesteads increased. The workers took along cats as ratters. Left more or less to their own devices, the working cats bred and went feral, expanding into unoccupied territory.

Feral cats are found in most habitats across mainland Australia, Tasmania and on offshore islands. The Australian feral population is not significantly reduced by seasonal weather changes. Australian ferals are found in remote areas (bush cats), while British/American ferals generally remain closer to human populations in search of shelter and food, especially in winter. Cats are intelligent and adaptable to many environments. Australian feral cats are found in coastal dunes, arid deserts, heath, scrub, woodland and temperate forest (and on the fringes of tropical forests), alpine snowfields, suburban and urban areas and rubbish dumps. The only real barrier to their success is cold combined with wet as become chilled. They can survive in dry conditions because they are predominantly crepuscular (dusk/dawn hunters) or nocturnal and get most of their moisture from their prey, reducing their dependence on free-standing drinking water.

Feral cats are normally considered to be solitary, pairing up at breeding time, but studies around the world indicate that they are solitary only in low density situations. In higher density populations (close to a reliable food source), they form colonies and exhibit behaviors normally associated with lions: communal kitten rearing, usurper tom cats killing kittens to bring females back in oestrus. There are observed instances of communal hunting behavior. In feral cat populations, food supply and climatic conditions provide natural biological limitations to its expansion.

Cats usually have 2-3 litters a year, but can breed up to 5 times per year (e.g replacing lost litters) and average 4 kittens per litter. Due to starvation and disease, few young survive to the weaning stage at 8-12 weeks of age. Surviving offspring become fully independent at 5-7 months, but may remain with the colony. Sexual maturity is affected by the bodyweight and seasonal influences - this is a biological adaptation to ensure reproductive success. Males are mature at 10-14 months (at 3.2 kg) but some 5 month old males have sired litters. Females generally become sexually mature at 6-12 months old (at 2.5 kg), but some can breed as young as 5 months.

Up to 90% of kittens/cats fail to survive their first year. This high mortality rate of young cats was once believed to make it difficult for a population to recover after culling, despite the cats' high reproductive capacity. This supposition is erroneous since after culling there is more territory/food/prey available per surviving cat hence more young cats survive. Only when the cats reach a threshold population does the mortality rate play a significant part in reducing reproductive success. Little is known of the lifespan of Australian feral cats. Ferals up to the age of 7-8 years of age have been recorded, but 4-5 years is more usual. This is comparable with studies in other countries.

Feral cats generally eat small mammals such as rabbits and rodents, although they also eat birds, reptiles, amphibians and insects and will scavenge from carcasses (e.g. roadkill) and rubbish dumps. Cats will also eat placental material e.g. from birthing ewes. In pastoral regions in Australia, young rabbits make up the majority of their diet, but in areas where rabbits are scarce, feral cats seek alternative prey including native animals.

IMPACT OF FERAL CATS ON ISLAND POPULATIONS

Island fauna and isolated mainland colonies are vulnerable to cats in general. Cats have been recorded on a number of off-shore islands: the Monte Bello group in 1912, Pelsart Island in 1913, Dirk Hartog Island in 1917 (attempts were made to remove them in 1976 to aid the re-establishment of the banded hare wallaby), Bernier Island in 1906-07 (though they had apparently vanished by 1959, probably through disease or malnutrition), North Island in 1960 (having been introduced after 1945), Rottnest Island and Garden Island. Some were introduced for rat and rabbit control, others were taken to the islands as pets and some were introduced to control native species perceived as pests by settlers.

Feral cat colonies have caused the extinction of a subspecies of the Red-fronted Parakeet on Macquarie Island and contributed to the extinction of the Tammar Wallaby on Flinders' Island. On St Francis Island, cats exterminated the brush-tailed bettong between 1859-1900, and are may have caused the extinction of the spectacled hare-wallaby and golden bandicoot from Hemit Island. Cats may also have suppressed re-establishment of Cape Barren geese on Reveby Island. Island-living cats suffer sue to their restricted diet; in a survey of cats living on an island off the coast of Los Angeles, USA, 22.5% showed liver damage due to inadequate diet.

In the early 1990s on Magnetic Island, Australia there was reportedly a huge cat problem. The island's Ranger box-trapped and killed around 100 cats each year. Mass poisoning was not an option because of the risk to wildlife and to owned cats.

Islands are usually small and isolated, hence impact of cats is greater and more obvious than it is on the larger mainland, particularly if cats are the only predator present on the island. Island animals are not replaced by incomers from neighbouring areas. The effect of humans, rats and mice on island species should not be disregarded. On mainland Australia, dingoes, foxes and feral dogs are also active predators. There are no foxes or dingoes in Tasmania yet there is little evidence to suggest that feral cats have had a major impact on the native wildlife there.

The removal of cats in 2000 caused "catastrophic" damage to the ecology of sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island between 2000 and 2007 according to an Australian Antarctic Division report in the Journal of Applied Ecology. Rabbit numbers have soared and they have caused so much damage to the island's flora that the changes can be seen from space and decades of conservation efforts have been compromised. The cats were removed in order to protect breeding penguins, but the subsequent increase in rabbits, rats and mice now threatens the penguins' habitat and chicks. Cats previously kept a check on rabbits (introduced for food in 1878) but were eradicated because they were also eating seabirds. With no cats to predate upon them, the numbers have risen to around 100,000 despite the use of myxomatosis in the 1960s. Their destruction of plant cover has made penguins more vulnerable to predation. The scientists behind the research say conservation agencies must "learn lessons" from the episode - in this case, the subsequent effects of removing a predator were not fully investigated. In the case of Macquarie Island, the Australian government plans to eradicate the rabbits, rats and mice (all previously controlled by cats) from the island using poisoned bait at a cost of Aus$24m (US$17m, UKŁ11m).

IMPACT OF FERAL CATS ON THE MAINLAND

Island cases are well studied, but the impact of feral cats on the Australian mainland is harder to quantify. Many factors affect native wildlife: Aside from cats, there are many factors are killing off Australian native wildlife: introduced herbivores (e.g. rabbits, sheep) compete with native animals for food and shelter; roadkill, habitat loss through clearing, grazing animals and urban sprawl; pollution; feral and domestic dogs, feral pigs (which are omnivorous and opportunist), feral goats, foxes, introduced birds e.g. crows which either compete with native birds or prey on small native species, traffic, over-clearing and overstocking of land (kangaroos are already culled because the land cannot support them and the introduced grazers), introduced goats, sheep, cattle and wild horses erode the land with their hard hooves). Additional pressure is put on wildlife by the development of land for housing/industry including the destruction of migration routes which once allowed animals to move from an exhausted area to a new one, deforestation, pesticides (rodenticide used to combat a mouse plague killed many native animals), poison (both deliberate baits and accidental spillages), traps and snares laid for cats but which kill and maim native fauna, humans who shoot anything that moves without positively identifying their prey. The list seems endless.

There are instances where feral cats have directly threatened endangered species. In 1990/91, feral cats reportedly killed many of the captive bred Rufous Hare-wallabies released in the Tanami Desert region; reintroduced individuals are more vulnerable than wild-bred individuals. Cats are considered a major cause of death in the only mainland population of the endangered Eastern Barred Bandicoot in Victoria, while a single feral cat was impacting an isolated colony of Rock Wallabies in tropical Queensland. Once again the cats were impacting isolated populations; such populations are effectively islands and therefore vulnerable.

In suburban environments, cat predation is a less important factor than the creation of a barren and hostile habitat through urban development. Far from being wildlife oases, gardens and parks are islands. Island populations are vulnerable to predators in the short term but vulnerable to inbreeding in the longer term. In suburban green areas and remnant habitats, cat predation may cause localized extinctions; but removal of cats allows an increase in introduced pests which compete with native species. That the cats are keeping other introduced pests in check is only discovered after the cats are removed and the native species continue to decline.

Very little is understood about the interactions of cats, foxes, native predators, native prey and introduced prey, except that these interactions are extremely complex.

Since the 1980s, anti-cat lobbyists have raised a hue and cry about the supposedly voracious alien predator spreading out of control across Australia: not a plague of land-hungry, habitat-destroying humans, but a plague of killer house cats and deadly, over-sized feral cats. However, feral cats are often hungry, contradicting their image as wanton killers-for-sport. Stray cats have multiplied throughout Australia, apparently driving indigenous species to extinction in their wake. With no natural enemies to keep them in check, feral cats are killing small native creatures whose evolution has not equipped them to deal with introduced carnivores in addition to the rapidly changing landscape.

FERAL CATS AS CARRIERS AND CONTROLLERS OF DISEASE

The Australian ecosystem is fragile and has been greatly disrupted by numerous introduced creatures including toads which are poisonous to all predators excepting one type of snake. Other introduced carnivores are foxes and dogs. Feral horses, goats and pigs cause erosion. Rabbits and farm livestock (cattle, sheep) compete for grazing. Since the 1800s, mankind has been the most destructive introduced species; clearing the native flora to make way for farms, roads, housing and industrial developments, killing native predators such as the thylacine to protect introduced sheep. Mankind is too far down that road to reverse, or possibly even to halt, the damage. Feral cat numbers are almost certainly declining along with native animal populations as a result of continuing loss of habitat and livelihood for both native and introduced species. Introduced species, which have lived alongside man for longer, simply decline at a slower rate.

Cats can have beneficial impacts on wildlife by stabilising numbers of rabbits and introduced rodents. They also have adverse impacts through predation on native species and through the transmission of diseases. Feral colonies may serve as reservoirs for certain diseases, including those transmissible to other species. They carry infectious diseases such as toxoplasmosis, sarcosporidiosis, bartonellosis (Cat Scratch Disease) and ringworm which are transmissible to native animals, domestic livestock and humans. However, cats control populations of rats which are recognized human health hazards.

Sarcosporidiosis causes significant economic losses to livestock producers in southern Australia because of condemnation of infected carcasses. Cats are necessary hosts in the life cycle of the disease organism, therefore feral cat control is considered the only means of reducing the occurrence of this disease. However, livestock competes with native animals, and causes land erosion/over-grazing. Arguments for the destruction of feral cats on the grounds of reducing sarcosporidosis are based on economic rather than conservation grounds.

Toxoplasmosis can cause damage to the central nervous system, blindness, respiratory problems and general debilitation in wildlife. It can threaten small native animals such as bandicoots. In humans, it can also cause mild debilitation, miscarriage in pregnant women and congenital birth defects (see Zoonoses article). Toxoplasmosis is also found in, and transmitted to humans by, sheep, undercooked meat and contaminated soil on vegetables/when gardening. It is potentially transmitted from cat to sheep and can cause ewes to miscarry (sheep compete with native grazing species and have led to habitat destruction through land clearance for farming). The threat to humans is minimal since good hygiene prevents its transmission and an initial infection gives immunity to re-infection. Most cats shed the Toxoplasmosis organism only once (initial infection) and remain immune thereafter.

In other countries feral cats may carry rabies but are not major vectors of disease since rabid cats do not exhibit the furious (biting) form of rabies and generally shun contact.

Cats also prevent the spread of some disease. They control rodents which are proven reservoirs for, and carriers of, disease. Due to superstition, cats were killed wholesale in 14th century Europe. A thriving cat population might have prevented the Black Death which killed a third of the human population of Europe (25 million people in 5 years). No longer held in check by cats, the rat population exploded and came into ever closer proximity to humans in search of food. Plague was transmitted via the rat flea which quickly spread the disease among rats in the high-density population. The plague bacillus is present in Australia and is a notifiable disease.

Rats also carry Weils Disease (Leptospirosis) which was first recognised in Queensland in 1934. Weils Disease, a notifiable disease, is potentially fatal and now in all parts of Australia. Rats also carry a variety of bacterial infections and can cause other damage to native wildlife (killing nestlings), property and livestock (killing chicks, breaking eggs). The rat and mouse population is already increasing in urban areas and has the potential to reach plague proportions.

COMPETITION WITH, AND PREDATION UPON, WILDLIFE

Urban cats come into contact with native animals whose habitat has already been disrupted. Even if cats are removed, those native animals continue to decline as they compete with each other and with introduced creatures for limited food supplies and remaining space in a hostile man-made environment. Being isolated from other populations, urban populations of native animals become inbred and susceptible to disease. Many are effectively island populations, trapped in parks and gardens.

In remnant habitats, introduced predators contribute to the reduction/extinction of less abundant species or those which present the easiest targets. Predators also prey on introduced pests such as mice, pigeons and rabbits which compete with native creatures. Removal of introduced predators leads to an increase in those pests as well as any increase in native creatures. The more adaptable pest species out-breed and out-compete native species. In an environment where around 60% of native species are predators, if a species cannot cope with predation , it is no longer a viable species. To make it viable the other threats, not simply the predators (native or introduced), must be removed. Those "other threats" are humans, livestock, habitat destruction and so on and so forth. Yet humans continue to crowd out native species and show no signs of removing themselves or their livestock from the continent.

Native fauna and flora on the Barkly Tableland declined alarmingly after human settlement. A third of mammal species became extinct and others declined dramatically. This created a situation where any predator had the potential to wipe out entire colonies of native animals or to prevent recovery and dispersal of native species. The major predator in the area is the feral cat. There are thousands of feral cats preying on a wide range of prey species. In the late 1800s, 1000 cats were set free to control rabbits. Dingo poisoning programs allowed the cat populatin to increase since dingoes compete with, and prey on, cats. The Aboriginals who used to hunt the cats for food have largely moved to missions and cattle stations. The removal of these natural population controls creates a situation where the only remaining limiting factor is the availability of prey.

In the past, assumptions about feral cat impact on wildlife have largely been based on suspicion, supposition and superstition. While the effects of cats on islands is well documented, the true impact of introduced predators in the remote bush is poorly understood. They prey on introduced rabbits as well as native animals. The population of prey in the outback is less dense so the effects of predation on native species is more pronounced. If the predators are removed, creatures such as rabbits can outbreed native creatures and devastate the fragile ecosystem before the native creatures have time to recover. Research indicates that cat predation on rabbits is extremely important in ecological terms and wholesale removal of cats could be far more dangerous than their presence, perhaps at a reduced level, in the Australian environment.

Since cats prefer rabbits, cats are rarely found in deep forest. Preserving old growth forest is one way of protecting native wildlife from cat predation and competition, and it also combats the growing land salinity problem. Land continues to be cleared for farming and building. Farmland is hostile to native species but ideal for rabbits and for the feral cats and foxes which prey on them. Buildings are hostile to native species, but attract mice, rats, sparrows and pigeons and hence the cats and urban foxes which prey on them. Ironically humans spend time and effort investigating ways of reducing the cat population in order to preserve native species, but every other human act seems geared to turning Australia into a cat-friendly habitat, in fact into an ideal habitat for introduced species in general. In the long term, the only species which will survive outside of reserves and zoos are those which can adapt to living in habitats shaped by man. The only animals adapted to such man-made habitats are those man brought with him, who have a long head start over the native animals.

Where rabbits are common they form the staple diet of cats: 54% - 94% depending on season. House mice are consumed when available. Smaller native animals are eaten in numbers proportional to their size to make up the diet. In areas where rabbits are absent, the cat must switch to alternative native species. In one study, after a crash in the rabbit population, cats and foxes were removed in one area but left in another. In the predator-free area, rabbit numbers increased 8 fold in 12 months. In the other area the rabbits only doubled. By keeping introduced prey numbers low and stable, boom and bust cycles which cause predators to switch prey are prevented, reducing predation on native animals. It has been virtually impossible to assess the impact of cats alone because they take the same prey as foxes and removal programs target both predators.

On Macquarie Island, the eradication of cats in 2000 allowed the rabbit population to soar to around 100,000 in 2008 (it had been reduced by 10,000 by myxomatosis in the 1960s), devastating the ecology and making penguins more vulnerable to predation. Rats and mice also increased dramatically, threatening the chicks. The removal of a predator has allowed other introduced pest species to thrive and cause huge damage.

The problem with predation surveys is that most collect data from statistically small samples in a single area whose geography and demographics are not representative of the whole state, let alone the whole country. The statistics are multiplied up with no adjustments being made to take account of regional differences. The results are what one would expect of a child's attempts at statistics and cannot be taken seriously. The recent Mammal Society survey of cat predation in Britain is a case in point, as was an oft-quoted earlier survey conducted in Oxfordshire. Many, if not most, Australian surveys fall into this category - localized, small sample, no adjustments when extrapolating. The discredited. but still quoted, Paton survey (cat predation data gathered from ornithologists!) is a case in point. Many surveys take the worst case scenario and present the extrapolated figures as the average rather than as the extreme example (perpetuating anti-cat sentiments). Only the Reark Survey into Metropolitan Cats seems to have collected and analysed (rather than simply extrapolating) data from a large sample in several areas.

Figures about cat predation on wildlife vary wildly and are inconclusive as cats take whatever prey is abundant. A NSW Parks and Wildlife study of 62 species of endangered mammals, birds and snakes made no mention of any of those species being endangered by introduced predators. A 1991 Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service reported that of 87 bandicoots examined, no adults had been killed by cats, but 40% of juveniles had been killed by cats. In Eltham, Victoria, an area where 80% of people owned cats or dogs, a wildlife rehabilitation expert of 30 years standing indicated that less than 0.5% of injuries to wildlife were caused by cats. A survey of injured wildlife admitted to shelters indicated 11% of admissions were due to cat attack. In one Melbourne wildlife shelter during 15 months, 272 injured native mammals were attributed to cat attacks; 242 being ringtail possums (the local abundant prey species). 25% percent of sugar glider corpses received at one shelter were reported to be due to cat attacks. Anti-cat campaigners proclaim that throughout the world at least 30 species of birds became extinct because of cats; this is far less than have become extinct because of humans (including dodos, solitaires, great auks, flightless moas). Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service reported that, of 513 threats to native birds, cats probably threaten only 3, but might be contribute to an additional 29 of these threats. Most studies conclude that cats seldom eat birds because of the additional overhead in catching them (town cats catch more birds because people - including cat owners - feed birds, attracting them into the garden and making them vulnerable to cat attack)

A 1991 seminar concluded that cats represent a significant threat to Australian wildlife, preying upon over 100 species of native birds, 50 mammals, 50 reptiles, and numerous frogs and invertebrates. There was especial concern about cats in newly urbanized areas preying on rare legless lizards - as if urbanization alone wasn't enough of a threat to the lizards. Cats kill prey up to their own body size (adult rabbits being about the upper limit) and conservationists fear that most of Australia's endangered and vulnerable mammals, birds and reptiles are in this size category. Smaller prey must be taken in larger numbers to make up the number of calories required by the cat. Smaller prey usually have higher reproductive rates; cats and mice/cats and rabbits have existed in a kind of arms race throughout Europe and Asia. If it is an arms race, then Australian marsupials haven't yet gotten off of the starting blocks.

Also in 1991 it was estimated that in one district of Hobart in Tasmania 65,000 native animals were caught by domestic and semi-domestic cats over 3 months. When these kinds of predation figures are extrapolated for the overall feline population of Australia they indicate that hundreds of millions of native animals are killed by cats each year. Those figures are valid only for those regional conditions; they are from a relatively small sample of cats with a high margin for error when extrapolated. It was also estimated that the approx 1 million domestic cats in Melbourne alone could be taking between 30 - 50 million prey items a year. Both sets of figures should be put into perspective using the far more comprehensive Reark Survey into the metropolitan cat, especially as 50% of pet cats do not hunt at all! Of hunting cats, nearly 40% caught rats and mice only, 24% caught introduced birds and only 4% of domestic cats caught native birds (the birds are attracted into gardens by feeding).

It was not until 1994 that the number of fauna caught was more accurately estimated when the Petcare Information & Advisory Service (PIAS) survey found that in 1993-1994 each metropolitan domestic cat caught an average of 4.76 prey. This works out at approximately 2.193 million native mammals, reptiles, amphibians and birds caught by 1.397 metropolitan domestic cats in the year studies.

In spite of conflicting data, it is said that the average domestic cat is kills an average of 25 native animals per year. This means Australia's 3 million pet cats kill 75 million native animals per year. Feral cats each require 300gms of flesh daily. If feral cats ate only native animals, each feral cat would need 70 native animals a week, 3,600 a year to survive (the average prey size was not stated). This could mean 12,000 million native animals killed each year by feral cats. A few cats specialise in hunting certain species, but this is atypical as most cats consume a varied diet. Ferals do not subsist entirely on native species in areas where rabbits and mice are abundant hence the figures are a worse case scenario, not an average.

Predatory behavior in pet cats is not reduced by feeding since cats hunt through instinct, even when not hungry. Hungry cats rarely play with prey as they cannot afford to let a meal escape. Collar bells on pet cats have only limited effect since cats are stealthy stalkers or ambushers and by the time the bell sounds, the cat is already making the final pounce.

In ACT, regular cage trapping confirmed a diet of human food scraps, native birds, reptiles, house mice, fish and vegetation. Elsewhere a study of scats from 48 cats showed that they preyed mainly on ringtail possum. Some cats were reported to bring in a series of the same species in a short time, suggesting that preying on a colony could cause local extinctions. This is atypical since cats generally prefer a wide a range of different prey and are unlikely to prey on any one species to the point of endangerment or extinction. Cats are opportunistic feeders, preying on the commonest and most available species rather than rare or endangered species; the cat bringing in the same species time after time would have done so because it was the commonest prey in the cat's territory. Cats will scavenge fresh carrion, including that of species they would not tackle as prey.

One researcher estimated that each cat killed at least one animal per night, totalling some 50 million victims a year. One cat in the Tanami desert in central Australia had been found to have eaten, in a single night, a marsupial mouse, a native rodent, a bird, two lizards and the front half of a large goanna (a large lizard). The researcher failed to mention that the goanna was probably scavenged. Two cats were autopsied from the Weipa region and found to have eaten skinks, a monitor, geckoes, spiders and birds. A feral cat on an island off Western Australian had eaten no fewer than nine introduced mice by 10 o'clock at night. Others point out that mice are introduced pests and the cat's predation on introduced, rather than native, species is to be applauded. Cats were, after all, once prized for their rodent-killing abilities.

Cats have co-existed with various native species for around 200 years (as long as 500 years in some parts), causing only localized extinctions. If during those 200 (or 500) years they had done even a quarter of the damage they are supposed to be doing to native wildlife, there would be no small native animals of any kind left in Australia today. The ecological balance has changed and is still changing, but mankind does not like the look of the new balance. If cats were removed from the Australian environment, what would happen? It's not the rosy image that anti-cat campaigners seem to believe in. Over 200 (or 500) years, the Australian ecosystem has been adapting to the presence of cats in a ruthless weeding out of less adaptable species.

Many species exist in reduced populations through human activity. Without humans, a new balance might be reached. Mankind cannot, or will not, change its living habits - land-hungry, resource-hungry, polluting, population continually increasing. Mankind is the most damaging species around. The removal of predators allows mankind to do more damage in their place.

What would happen to native species whose native predators have been reduced or become extinct? What would happen to native species whose populations have been unnaturally advantaged by human colonization and whose populations are partly regulated by cats? Those species are now at least partially dependent on the cat for population regulation and natural selection; otherwise they prey species would become overpopulated, full of weak and sickly individuals and might eat itself out of house and home. Though a native species might increase its population rapidly (if foxes and dingoes were also removed and introduced competitors eliminated), it would compete with other native species forced into ever-smaller habitats by human activity.

What about native species on whom cat predation is minimal but who compete with introduced animals such as rabbits, rats and mice? If introduced predators are removed, the introduced species have a higher reproductive rate, are more adaptable and would swiftly out-compete native species or cause habitat damage as has been seen on Macquarie Island. Marsupials only survived in Australia because it was isolated from other lands where placentals were present. In South America, placentals out-competed marsupials in prehistoric times. Australian wildlife, unfortunately, catching up. In effect, Australian wildlife is an island population trapped in prehistory. In nature less efficient species are replaced by more viable species through predation and competition. Humans have precipitated events which occurred naturally elsewhere in prehistoric times. The effects cannot be undone, only slowed.

It may well have been better if cats had never been introduced to Australia in the first place. Hindsight is an exact science. However, the global ecosystem is a system in constant flux, with or without the influence of modern industrialised humans. Even if it is possible to remove cats - or other introduced animals - from the Australian ecosystem, it risks doing far more harm than good at this late stage.

TRADITIONAL METHODS OF CONTROL

Traditional control methods include shooting, trapping, baiting (poisoning) and barrier fencing. Trapping is difficult and labour intensive as feral cats tend to be trap shy and. Cats are by nature cautious eaters and do not take baits as readily as do rats, dingoes or foxes. 1080 poison (used against dingoes) also kills cats, but is highly indiscriminate and kills many native species which scavenge the baits. Feral cats may be poisoned with manufactured 1080 Feral Cat Baits (4 g baits containing 6 mg of 1080); the use of Feral Cat Baits is restricted and each application needs the permission of the Agriculture Protection Board.

An unidentified bush-worker from north Queensland from 1944 to 1970 noted that there were massive and frequent strychnine-poisoning programmes against dingoes (wild dogs), but that the cat wasn't regarded as a pest. Random baiting over 20 - 30 miles with strychnine and later with 1080 took relatively few cats, but accounted for huge numbers of birds of prey. For every few dingoes killed, the poison-laced baits killed hundreds of predatory birds were killed, as were goannas (large lizards), feral cats, scavenging omnivores, both native or introduced, and also echidnas which ate ants attracting to the baits and ingested poison along with the ants.

Concealed baits covered with bark, grass or placed inside a fallen hollow log killed fewer birds and more cats. A rabbit trap with fish oil decoy and strychnine pads on the trap's jaws would kill a trapped cat in two to five minutes (probably much longer) because the cat tore at the strychnine pads and was poisoned. The bush-worker claimed to have killed over 500 cats over 40 years in the bush. When he found a litter of feral kittens, he removed one from the nest and coated its scruff with strychnine, then clubbed to death the other kittens. The mother was poisoned when she moved the surviving kitten. The kitten then starved.

In order to selectively poison cats and exclude birds from the poison bait, the bush-worker developed a specialised baiting device. Built of fibreglass, it relied on the cat to paw out a poisoned bait. This was developed in near secrecy because of the cat lobby which he regarded as misguided but vocal and whom he claimed had to be re-educated. Boiled and smoked liver baits and smoked oily fish set with gelatine were found to be effective. Rather gruesomely, he tested baits on a subject cat kept at home. This was often starved so that it could be tested with different baits.

Live-trapping is only effective in urban areas where the cats are attracted to rubbish dumps etc. Live-trapping requires considerable time and effort and non-target animals should be released. Outside of urban areas, traps are often not checked regularly resulting in the deaths of trapped animals including native animals. Trapped feral cats are difficult to handle and usually while still in the trap. There has been research into improving baits and traps to control feral cats, including visual lures (e.g. feathers) and scented attractants (e.g. tuna oil). A program by the NSW. National Parks and Wildlife service is set to take off to trap feral cats with a sonic trap which gives out cat calls and is scented with cat faeces and urine to further lure and trap the cat. The sonic trap has apparently been 100% successful in elimination of feral cats on an island off the Western Australian coast, however no data was provided on the relative success rates of sonic and non-sonic traps.

Shooting is an opportunistic method, but is ineffective for population reduction in rural situations since cats from neighbouring areas quickly recolonize. Night shooting using a spot light and a high powered rifle (shotgun at short range) can be effective in localized areas. The army have been used to clear areas of feral cats by shooting, but the areas were quickly recolonized from neighbouring areas. Surviving cats were reported to be even more elusive.

Feral cats have been eradicated from some offshore islands using traditional control methods, but eradication of ferals from the mainland is impossible. Due to the well-known vacuum effect, an area cleared of cats is seen as available territory and an unexploited food source and is rapidly recolonized by an influx of cats from neighbouring areas. Barrier fencing is necessary to keep an area feral-free. If the cats are not excluded from the cleared area, then over sustained periods of lethal control (e.g. every 6 months) the offspring of the remaining cats, and the incoming cats, will be smarter and faster than previous generations. Lethal control is what cats naturally do to prey species, taking the weakest, slowest and sickest. It is called survival of the fittest. In places where feral cats are a problem for native wildlife, sustained lethal control may worsen the problem. The only long-term effective measure is fertility control.

On the borders of national parks close to suburbia, cat eradication involves poisoning feral and pet domestic cats with aspirin or paracetemol in a bowl of milk. The dead cats are usually found close to the bowl. Antifreeze in milk is also used. None of these substances are humane and they cause unnecessary suffering; they may also be eaten by the very native species anti-cat crusaders claim to be protecting. Although local residents may be warned of the poisoning (though poisoned baits are also laid without warning by individuals), dozens of pet cats are killed. It is not natural for adult cats to drink milk unless they have become habituated to being given milk. Poisoned milk is therefore more likely to kill pet cats (who are habituated to drinking milk) than kill feral cats (not accustomed to drinking milk after weaning); while it kills cats, it does not address the feral cat problem.

Barrier fencing is the most effective traditional control method against a number of introduced species including cats, foxes and rabbits. Unfortunately the high cost makes it useful only for small areas of land and wildlife reserves. The fences need regular maintenance to repair any holes; native wombats are notorious for damaging barrier fencing and rabbits quickly exploit any breaches in the fence. The fences should also go several feet down into the soil because rabbits are burrowing animals and rabbits reaching the inside of an enclosure would have no predators. Fencing is also a barrier against native species trying to move onto, or off of, the enclosed area. Enclosed areas lead to genetically isolated populations (artificial islands) which become inbred and highly susceptible to disease if left unmanaged.

Biological control agents, as well as toxins and pesticides, are also being investigated. A biological control agent would need to be humane and virulent. Domestic cats would also need to be protected from any agent that was released e.g. by vaccine which must be made available to pet owners at no cost otherwise lower income owners are discriminated against. Orally administered contraceptive vaccine has been developed in the USA, but is not yet available outside of laboratory trials. Once again there is the problem of getting the cat to eat the bait. This is humane and acceptable to most people, but anti-cat factions argue why bother - if you can get a cat to eat a contraceptive bait, you might as well get it to eat a lethal bait.

It is believed that biological control agents are needed to control cat numbers in arid regions and wet-dry tropics and for long term management of the feral cat problem. Five feline viruses are potentially useful. However vaccines are not available for all the diseases, endangering pet cats. Development of resistance will occur in the long term and some of the diseases are unsuitable as they cause long unpleasant illnesses. There is also the danger that viruses may jump the species barrier and devastate native species.

It has often been suggested (by politicians rather than biologists) that cat flu be introduced into the feral cat population as a means of control. Cat flu is caused by one of two viruses: feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus (also called feline rhinotracheitis virus). These viruses are endemic in most feral cat populations; cat flu is one cause of kitten mortality. Consequently, many feral cats already have antibodies to these viruses and would be immune to the virus if it was deliberately introduced. Most healthy, well nourished adult cats recover from cat flu. Transmission rates of the cat flu viruses are low apart from in high-density populations. The virus would cause more damage to urban ferals and urban domestic cats than to rural cats. The use of a feline virus such as cat flu or Feline Leukaemia (a slower killer) is opposed by health authorities. It would lead to a situation akin to myxomatosis in rabbits; an initial dropping off in numbers followed by an increase of disease resistant animals.

Scientist are attempting to develop a biological contraceptive for foxes. This involves using a modified virus to immunise foxes against their own sperm or eggs and effectively sterilising them. If successful this type of biological sterilisation may be a humane means of control which is suitable for adapting to cats. However it would also affect pet cats and fancy cat breeding programs. In cats, biological contraception appears to have been overtaken by the development of the FTC2 feline-specific toxin which kills in an apparently humane manner.

In America, there is a significant amount of research into contraceptive vaccines. Scientists there have developed genetically engineered bacteria that can be used as an oral contraceptive (immunocontraceptive) in cats. The vaccine uses a strain of that does not cause disease. The contraceptive vaccine is still in the very early stages and must first be tested on laboratory cats.

The contraceptive vaccine causes the body's immune system to produce antibodies which block interaction of the egg and sperm and prevent conception. This vaccine can be placed in feral cat bait. The correct dosage hasn't yet been worked out and the side-effects are not known. Also, it isn't known whether the cats must be revaccinated regularly or whether a single dose causes lifelong sterility. If the cats' immune response is triggered by a sufficiently high dose, the sterility should be irreversible. An area would have to be baited several times to ensure that all cats were rendered sterile. A small number will eat an amount too small to be effective or may not eat the bait at all hence the need for regular baiting.

The vaccine is intended for female cats, to block conception, but baits will also be eaten by male cats. Though the males will produce antibodies these should not cause adverse reactions with his own tissues. The vaccine will be cat-specific so other scavengers who eat the bait will not be affected. This is essential if the oral vaccine is to be used in areas where there are endangered species. If successful in producing lifelong sterility without harmful side-effects, it could also be used as an easily administered alternative to surgical neutering of pet cats.

This is not the only development. A vet at the University of Georgia, USA, has developed an injected sterilization drug, based on similar research. It is being tested on dogs at present. In adition, the Winn Feline Foundation, USA has given an to a team at the University of Florida for researching non-surgical alternatives to neutering feral cats. SpayVac ™ has already been proven to reduce fertility in Barbary sheep, rabbits, and some seals species, and may prove effective in sterilizing feral cats. These would not be feasible solutions to the massive population of outback ferals, but might be suitable for managed urban colonies if the effects of vaccination are permanent and if vaccination is cheaper than surgery.

A substance called mibolerone might be an alternative to surgical spaying. Mibolerone is chemically similar to Mifepristone (an ingredient in RU-486). It is an androgen (male hormone) steroid which blocks the production of progesterone (female hormone needed to sustain pregnancy). It is not cost-effective due to formulation and the quantity currently manufactured. At one stage there were plans in the US for a birth control dog food and the concept could be applied to both feral and domestic cats.

In foxes, another serious introduced pest in Australia, the use of sterile decoys has been suggested as a method of population control. It was proposed to remove the ovaries of vixens (rendering them sterile) and to put those vixens permanently on heat using an oestrogen implant. The super-sexy foxes, nicknamed "red-hot mommas" would attract every male fox for miles around and disrupt the mating season. The theory was that males attracted to them would be too busy to mate with fertile females, thus reducing the birth-rate. The effect of being permanently on heat would take its toll on the vixens, probably causing womb infections.

Could this also work with cats? It is unlikely to even dent the feline reproduction rate because of their very promiscuous mating habits. Male cats compete over females and, even if super-sexy sterile females were present, the toms would still mate with several other females in the area. If vasectomised tomcats were used instead of sterile females, the females still mate with a number of males and would still bear the normal complement of kittens.

Victoria's Institute of Animal Science vertebrate pest research head, Clive Marks referred to foxes as Australia's potential environmental disaster of this century.

Researchers from the Victorian Institute for Animal Science have developed a humane cat-specific chemical toxin called FTC2. Until FTC2, there had been little success in developing biological or chemical control agents to deal with feral cats without also affecting native species which scavenged the poisoned baits. Wider trials are required, but there are encouraging signs that the toxin would be suitable for use against feral cats throughout the country.

FTC2 interferes with oxygen take-up and causes death through oxygen deprivation (i.e. suffocation). The chemical is claimed to be harmless to Australian native animals. Such a toxin is unsuitable for use in countries where there are wild species of cat or free roaming pets. The cat eats poison bait, becomes unconscious and then dies. It is claimed that cats which consume a sub-lethal dose will regain consciousness and recover fully. There is no information about a specific antidote for the poison should a pet cat ingest a lethal dose and it has been claimed that it will be used areas well away from pet cats (the vacuum effect applies). The cumulative effect of several sub-lethal doses was not indicated nor the time between ingestion of the poison and death.

The Australian RSPCA and several other cat-friendly organizations have not opposed the use of FTC2 as it is proven to kill in a humane way; however others have expressed reservations about its misuse or to malicious individuals obtaining and using FTC2 on neighbours' pets. Misuse is not inconceivable; in the UK, a single cat-hater poisoned a large number of pet cats with cyanide laced sardinesIn Australia there are reports of 1080 poison being misused despite tight controls. FTC2 must therefore be tightly controlled.

Where conventional poisons are used, individual poison-resistance or poison-tolerance occurs due to continued low-dose exposure to a poison (a case in point is nicotine tolerance in human beings). In fast-breeding creatures, poison-resistant individuals occur through mutation. Often poison-resistant individuals already exist and simply take advantage of reduced competition for food and space. When they breed, they pass on the poison-resistant trait and resistant individuals eventually outnumber susceptible individuals (as with disease resistance e.g. myxomatosis). If FTC2-resistance does not, or cannot, develop then the use of species-specific poison offers a humane, medium term solution and may reduce numbers to a level manageable by other means. In remote areas, the effectiveness of FTC2 in controlling bush cats has yet to be demonstrated.

Feral colonies often occur near rubbish dumps and to dumpsters behind restaurants where they scavenge food scraps and hunt mice, rats and native animals attracted to the dumps. Studies of rubbish dump colonies have been conducted in several countries including Australia.

The feral populations at the studied dumps were estimated by live trapping and tagging and studying how many tagged cats were later recaptured. The cat populations were found to be lower than previous studies predicted. Euthanasia of all cats trapped was used to investigate population recovery. The population took approximately 6 months to recover to 70% of its original size. Cat population turnover was related to births, deaths, immigration and emigration. Ferals from neighbouring areas and, to a lesser extent, stray or abandoned domestic cats are attracted to rubbish dumps due to the ready supply of food. Unneutered cats of both sexes may be attracted to colonies where mates may be found.

Most of the rubbish dump cats were diseased. Common illnesses were Upper Respiratory Tract Infections (viral), dental/gum disease and FIV (especially in adult males which often had secondary infections). FeLV was not detected, suggesting that the disease is not yet widespread among Australia's free-ranging cats. There was a high incidence of chronic disease, but this did not affect the rate of reproduction.

Cats on rubbish dumps can be beneficial because they control rat and mouse populations. They are also considered a problem because of interaction with neighbouring feral populations and as reservoirs of disease for domestic cats, wildlife, livestock and humans. Studies suggested that the problem can be reduced to a negligible level by six monthly culling. Rats and mice would also have to be controlled if the cat population was reduced or removed.

An alternative method used in Britain and America is colony management (TNR: Trap, Neuter, Release). Diseased cats are euthanized, tame cats (strays) are homed and the remaining healthy ferals are neutered and returned to site. The cats continue to control the rodent population but the cat population can only increase by immigration of new cats into the area (many would be repelled since cats a territorial and neutered cats do not seek mates). Such a colony would decrease due to natural deaths while any colonising newcomers are trapped and either euthanized or neutered according to their condition and the current colony size.

There are several well known groups across the commonwealth and the country that are in the business of Trap-Neuter-Return to form a smaller, stable feral population which does not increase through breeding and which repels incoming cats. Given the problems of rats, mice and rabbits populations exploding if cats are removed wholesale, this approach is feasible under certain circumstances. Some biologists consider this approach to be a double edged sword since on one hand, TNR ensures that the cats they have caught will not create any future litters of unhealthy kittens that will have to prey on small wild animals. On the other hand they are returning a predator into the environment. TNR is only feasible in wildlife-poor urban areas since it is too time and labour intensive for the more remote and generally uninhabited areas.

CALLS FOR ERADICATION - A POLITICAL ISSUE

Control of feral and domestic cats is a regular political item, most often around the time of local or national elections.

Sir: Our Federal Government would have to be the most generous in our history! Recently, it gave a handsome $47,074 to the West Australian Cat Welfare Society to create five jobs for five unemployed people. The jobs? Catching stray cats at a whopping $9,414.80 each for 26 weeks, or $362.11 each per week. [. . .] No wonder the PM (Call me Bob) is so popular. If I could get handouts like these, I would vote for him too. - Dan O’Donnell, Stafford Heights (Qld). (Letters. The Sydney Morning Herald, 8th June, 1984)

In September 1992 NSW Parliament's North Sydney member Phillip Smiles called on environment ministers, local government ministers and agriculture ministers to develop legislation to halt the spread of feral cats. Smiles alleged that up to 40,000 wild cats were roaming wild in NSW's parks and bushland and that this was an environmental disaster since feral cats required 300 grams of flesh each day to survive, equalling 3600 small animals each year. He told Parliament that the cats were literally roaming around in dozens around Sydney's parks and bushland. In fact cats do not form packs, unlike dogs, but a group of cats may be attracted into an area by a single food source e.g. rubbish.

Smiles said that feral cats look similar to domestic cats but are thinner and more ferocious. He wanted legislation to be introduced to give dog catchers and rangers the power to catch and destroy feral cats, saying that currently, if they did find them there was nothing they could do. In actuality feral cats are considered vermin and are culled throughout Australia so it was erroneous to say that rangers could do nothing about them. The main problem is not usually legislation, but lack of funding! Since stray cats were alleged to contribute to the feral population in urban areas, Smiles also called for increased control over domestic cats including registration, neutering and confinement of domestic cats to lessen the chance of them becoming feral.

In 1996 Australian MP Richard Evans called for all cats, both domestic and feral to be eradicated because they prey on wildlife. This caused protest from animal rights groups and pet lovers in Australia and around the world. Evans wanted Australia to be feline-free by 2030 (some authorities reported 2020) and he called for a fatal virus to be unleashed on killer wild cats which roam the outback massacring birds, native marsupials and other animals. He portrayed those cats as monstrous creatures, quite unlike the pet cat. He also called for a law requiring pet cats to be neutered so they could not breed and would eventually die out. Until then, a cat registry and cat curfews should be put in place. People would not be allowed to acquire new cats . About one-third of Australian households own one or more cats.

"I am calling for the total eradication of cats in Australia," he proclaimed, putting the issue on the national agenda. He added that while cats may be playful and affectionate at home, they are voracious killing machines outdoors. Evans blamed cats for the extinction of at least nine native Australian species. Several species are already extinct or extinct in the wild: the pig-footed bandicoot, brush-tailed bettong, rufous hare-wallaby and a dozen other birds and marsupial species unique to Australia. According to environmentalists, scores of other species are endangered, including woylies, boodies, numbats and potoroos.

He ignored the politically unpalatable fact mankind is far more guilty of causing extinction. Scores of creatures have fallen victim to mankind's voraciousness for land and resources Despite the human impact, Evans claimed that "Cats are responsible for 39 species being either extinct, locally extinct, or near extinct in Australia." He claimed that domestic cats each kill an estimated 25 native animals a year, and wild cats kill as many as 1,000 a year, according to the National Parks and Wildlife Service. In fact these figures were political hype and not borne out by other studies. In other words, he used statistics like a drunk uses a lamp-post - for support, not illumination.

Though Evans admitted that a cat-free continent may be beyond reach, he gained wide support with his proposal to kill all cats by the year 2020 (or 2030) by neutering pets and spreading fatal feline viruses in the wild. The virus proposal recalls an attempt earlier in the 20th century to eliminate introduced rabbits using the myxomatosis virus (white blindness). Widespread alarm and some accidents were caused as thousands of dying rabbits staggered onto highways. The rabbit population recovered and is descended from myxomatosis-immune individuals. In the long term, a cat virus will have the same effect. With the persuasive argument that the survival of native fauna is at stake, a hatred of cats swept Australia, fuelled by environmental extremists and causing many cat owners to confine pets indoors to avoid cat-killing vigilantes.

The Australian RSPCA agreed that cats should be controlled, but called total eradication "outrageous and unnecessary" (according to some Australian cat lovers "The RSPCA here are only interested in publicity for themselves, not in helping the cat situation"). Nancy Iredale of the Cat Protection Society called Evans' proposals laughable and found it hard to believe that people were taking him seriously. He would be opposed by humane societies since cats gave so much pleasure to people. The Cat Protection Society also protested. Humane societies stated that responsible pet ownership and government regulation would solve the problem better than mass killings, which only create a temporary dip in cat population. Leo Oosterweghel, director of the Royal Melbourne Zoological Gardens, agreed that cats must go, but was concerned that the demonizing of cats was leading to a rise in cruelty toward them. He reported that in Queensland, people were getting out golf clubs and clubbing cats; it had became a sport.

However, other wildlife experts backed Evans' plan. Conservationists had been warning for years about feline colonization, but only now was their cause taken up, albeit as a nationwide alarm being met with anguished opposition from cat lovers. Andrew Leys of the NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service supported Evan's plan but could not see it happening in practice. He felt that the practical solution was to manage the population rather than eradicate it.

The RSPCA warned that as a result of the anti-cat message, 75% of Australians viewed cats as the devil incarnate. One Sydney journalist told a visitor to do Australia a favor and kill a cat: "What do you want? Do you want cats or do you want koalas?" Unfortunately, the anti-cat message is being taught to children. Children are impressionable and are being encouraged to hate and even to hurt cats rather learning about responsible ownership, neutering, microchipping/tattooing, curfews and confinement. This schoolroom propaganda is guaranteed to breed a generation of anti-cat adults.

In the tropical Northern Territory, annual flooding flushes feral cats up into the branches of trees. Park rangers go out in boats at night and shoot them by the thousands. They flash their floodlights down the rivers and the eyes of the cats reflect the light, by aiming at the eyes the rangers are guaranteed a quick, clean kill. Rather than extolling this as a humane method (much like lamping of foxes in Britain which uses the same principle of reflected light) Evans enthused that the cats eyes light up like Christmas Trees. His enthusiasm is suggestive of an unbalanced mind, something remarked upon by my private correspondents.

The Australian Veterinary Association strongly condemned Evans' suggestion. Their animal welfare spokesperson, Dr Jonica Newby, said such Evans' proposals would simply result in denying the third of Australians who own cats the companionship and health benefits that cat ownership brings, but would have no overall affect on the feral cat population:

"The inference is that domestic cats are one short step away from becoming feral cats - which is not the case. Studies show that the impact of domestic cats on endangered native wildlife is minimal - the endangered species rarely come into contact with domestic cats, which live mainly in the cities," she said, "Feral cats have a life cycle largely independent of the domestic cat population. Far from being a recent phenomena, many scientists believe that feral cats have been here for up to 400 years as a result of contact from our near neighbours. The idea that you can eradicate feral cats simply be eliminating the domestic cat population is unrealistic. Mr Evans would be better served contacting the Australian National Conservation Agency, which is looking at less disruptive and destructive way to manage feral cat populations."

Dr Newby said the level of responsible cat ownership in Australia was one of the best in the world with one of the highest levels of neutering of domestic cats (91%) and about half of these cats being kept inside at night. She said, "Education of domestic cat owners and controlled management of the feral cat population is the key to controlling the impact of cats on native wildlife."

TOTAL ERADICATION - A NAÏVE DREAM

Total eradication has been attempted in other parts of the world, but in areas as large as the Australian continent it is a vain hope. My article Why Feral Eradication Won't Work explains why. Evans' statement that he wanted to completely eradicate cats - domestic and feral - from Australia and the outlying islands shows ignorance of studies worldwide.

Anyone involved in feral control knows that it is impossible to trap, poison or shoot 100% of cats. Survivors become more cautious and continue to breed. Their food supply is more abundant due to less competition from other cats. Deliberate introduction of disease creates naturally immune cats which repopulate the area. Even with poisons, a few individuals will be naturally immune and will breed. Some take sub-lethal doses and recover; they learn to avoid the particular odour or taste associated with baits and their kittens will learn from observing the mother avoiding the baits.

As mentioned much earlier in this article, there is an almost endless list of factors which adversely affect native wildlife. Habitat loss is probably the most devastating factor as it forces animals into smaller and smaller areas which are rapidly exhausted and brings the animals into conflict with humans including farmers. Though the cat isn't innocent, it is a convenient a scapegoat for diminishing wildlife due to a host of factors including the vast amount of damage caused by the land needs and carelessness of introduced human beings. One zoologist reported that if cats had done even a quarter of the damage claimed over the last 200 years there would be no small native fauna of any description left in Australia!

Evans, an eradicationist, claimed that people would not be made to destroy existing pets but that no more cats could be bred and no further cats kept as pets once an existing pet had died. Yet there were reports of cats being stolen and destroyed as 'strays' not to mention pets which were deliberately killed by cat-haters encouraged by reports of cats being the sole reason for wildlife diminishing. At the same time, Australian quarantine restrictions were being reviewed and if reduced would make it easier to import pets.

There is also the naive belief that once the cats are eradicated, the original Australian fauna and ecosystem will re-establish themselves. The introductions of rats, mice, European birds, farm livestock and species such as foxes, rabbits and toads, coupled with the extinction of native predators and destruction of habitat, means that the elimination of a single "pest" species will not miraculously restore the old order. The damage that has been done cannot be undone and the true culprit is humans and their ways, though no-one seems about to clamp down on human reproduction.

A apparently mainstay of the anti-cat crusade is John Walmsley, a conservationist who publicizes his cause by wearing a cat skin on his head like a coonskin cap, its small flat face looking out over his forehead. Walmsley, of Earth Sanctuaries Limited, has claimed that the only good cat is a flat cat (or dead cat) and has shown off the decorative cat-skin friezes on his walls. He has publicly boasted of the number of cats he has shot and of when he killed his first cat, but he has also contradicted these claims and stated that he has never actively killed cats. I find it impossible to trust a person who makes contradictory claims depending on who is listening and the likely reception his words will have. However he is dangerously persuasive in inciting others, who may rely solely on his words and not on balanced studies and unbiased information, to kill cats.

"The biggest problem with wildlife we have in Australia is domestic cats," he said. Walmsley wants people to love Australia's indigenous animals as much as they love cats, and has been trying - without great success - to persuade Australians to adopt a variety of marsupials as pets. "The bandicoot makes an absolutely delightful pet," he said. "It is the marsupial rat, I suppose. You can house-train them and they'll eat the mice in your house. The quoll makes a wonderful pet. It filled the niche of the cat before the cat came to Australia. The quoll will eat your mice and you can put it out at night. The most wonderful pet of all is the platypus. They are charming, absolutely delightful. I don't know why Australians don't have platypuses as pets." He didn't mention the fact that they have nasty poison spines on their legs!

Promoting the adoption of native species as pets is dangerous. It leads to animals being taken from the wild, often by killing the mother. It leads to unscrupulous breeders and to owners who, having tired of their pet, dump it back in its "native habitat" despite the fact that it was captive bred and will not survive in the wild, or that they are dumping it in an unsuitable habitat for its species. Taking animals from the wild reduces the gene pool and causes the wild species to decline further through inbreeding. If Walmsley's argument is followed to its natural conclusion, much of Australia's native wildlife will be living indoors in unsuitable alien environments!

The cat problem needs to be put in perspective with the human problem, but comments made by Earth Sanctuaries Limited in 1995 demonstrated a refusal to acknowledge the impact of human activities in declining wildlife, "It has now been proven beyond all doubt that cats are the number 1 problem in regard to Australia's loss of wildlife. Australia is, as you are obviously not aware, losing mammal species faster than the rest of the world combined. There are no areas where traffic accounts for more wildlife than cats. Earth Sanctuaries have never carried out programmes against cats other than removing them from our areas. In fact our method of creating feral-proof areas means that we do not need to destroy cats as do other conservation areas. It is well known that the cat came to Australia 500 years ago. It is also well known that it did not penetrate Australia until it got help from European settlers. There are no organisations in Australia controlling cats by humane methods as you state. There are organisations claiming that cats should be controlled by humane methods. There is a big difference."

The statement either ignored, or demonstrated ignorance of, TNR schemes in operation in some Australian communities as well as ignoring surveys by WIRES. It has not been demonstrated that cats are the number one problem with regard to Australian wildlife; it has been demonstrated beyond doubt that humans are the number one problem. Having run out of arguments and with no undisputed statistics to support his claims, the statement included a personal attack, "You are obviously in need of someone to hate and you obviously do not care who. The total cause for this [wildlife] loss is cats. You obviously hate wildlife. You obviously have a curious interest in cats. I feel sorry for you."

Personal attacks in the absence of valid data are generally indicative of obsessional personalities unwilling to consider any valid discussions which contradict their personal worldview. In fact, it is that sort of comment which is used for inciting anti-cat feeling by telling people that liking cats automatically means a hatred of wildlife and that an interest in cats is wrong or misguided. Such comments are particularly well-designed to placate those who don't want to hear that humans are partly, if not mostly, to blame for declining wildlife. It is not surprising that the anti-cat movement consider him an inspiration to their cause.

It is easier, and politically useful, to deny that humans are a cause and to focus narrowly on one of the other causes (one whose removal doesn't have apparent adverse effects on economic concerns), blaming one contributory factor as being the single cause of the problem. Resorting to personal attacks undermines the argument by demonstrating uncertainty about the validity of one's other arguments.

In The New Scientist of May 21, 1994, Ian Anderson published a piece titled "Should the Cat Take the Rap?" which discussed the issues surrounding cats and wildlife in Australia. It mentioned David Paton, a professor credited with triggering much of the anti-cat sentiment nationwide and subsequent measures against cats. Anderson's article noted that Paton's cat predation surveys generally included only people who belonged to bird-watching societies, and that he had extrapolated this biased data to make sweeping estimations of wildlife predation nationwide. Paton then published his severely flawed and unrepresentative interpretations with much fanfare. Thus began a new era of scapegoating of the cat in all its forms - feral, stray and pet.

John Egerton at the University of Sydney was quoted as saying Paton's work was biased and that building national campaigns on such a basis is wrong. Paton himself admitted that some of his studies were not controlled, but felt that his overall conclusions were sound despite using data from existing anti-cat households rather than from a mix of households. Other scientists were reported as saying that humans' destruction of habitats and other introduced animals (feral and livestock) are much more to blame for dwindling numbers of Australian native animal species than is any single predator species. But Paton had already captured the public's attention and re-ignited a simmering anti-cat feeling.

The New Scientist article said that in many instances, government and public had taken up a battle against cats. Car bumper stickers made fun of killing cats and a private wildlife sanctuary sells "Davey Crockett" style hats made of cat skins. Some state and local governments imposed night curfews on cats, limits on numbers of pet cats, or even knee-jerk bans on cats as pets. Western Queensland was using Army marksmen to shoot feral cats and at the time of the article, a federal wildlife office was investigating the possibility of releasing biological agents (viruses) against a number of introduced species; either to sterilize the animals or to kill them.

The article concluded that cats do indeed prey on many species, but the extent to which they threaten the country's wildlife is unclear. Many articles about declines in birds or other animals blame humans' laissez-faire attitude throughout history. In more recent times, more people are aware of wildlife declines and many want to take action, but problems occur when the actions are poorly researched or people jump onto bandwagons. The end results are, just like before, destruction of parts of nature tipping it further and further out of balance.

In March 2002, Victoria's Institute of Animal Science vertebrate pest research head, Clive Marks said that foxes "could be the environmental disaster of this century". Foxes were introduced into Australia to provide sport.

Many people do not see cats as having any "native" rights on the grounds that cats are not a "natural" or desirable part of an ecosystem because in many cases the cats were introduced by humans. However, what about the introduction of other species throughout history? If removal or destruction of introduced species were the answer, then how far back should conservationists go in restoring an area's authenticity? For example, cats have lived in Britain at least from the time of the Romans. To restore the authentic British ecosystem would mean major re-forestation, elimination of several species now regarded as native (including certain deer, plants and trees) and reintroduction of wolves, beavers and aurochs. Even rabbits are an introduced species in Britain, taken there by the Normans who valued them as a foodstuff. How far back should Australians go in restoring the ecosystem? Are there reliable records of the original state of the continent? Are they willing to tear down towns and factories, remove livestock and replant trees? Of course not; people want a simple fix and a convenient scapegoat. There are no simple fixes in life and when the scapegoat has gone, the problem is still there.