WHY FERAL ERADICATION WON'T WORK

The following article was originally written as two separate articles concentrating on feral control in Australia. These have been expanded to refer to feral control in America and Britain with additional summaries of cat welfare/control in Canada, Singapore and Hong Kong and combined into a single source-work for cat workers. There is some overlap between the two sections. A few minor updates have been made, but the original information has been left intact as a snapshot of the situation in 1994/5.

|

Why Eradication Won't Work (1994/1995) |

Methods of Eradication |

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Cats Protection Paper on Mammal Society Survey Domestic Cats - Wildlife Enemy Number One or Convenient Scapegoats? |

This is the original unexpanded 1994/1995 article.

In parts of Australia and America there is talk of exterminating stray/feral cats to protect wildlife species from an 'introduced predator', 'non-native animal' or 'an invasive species'. Though wholesale extermination appeals to those who oversimplify the problem and view cats as the agents of wildlife depopulation, extermination just isn't that simple and is ultimately counter-productive.

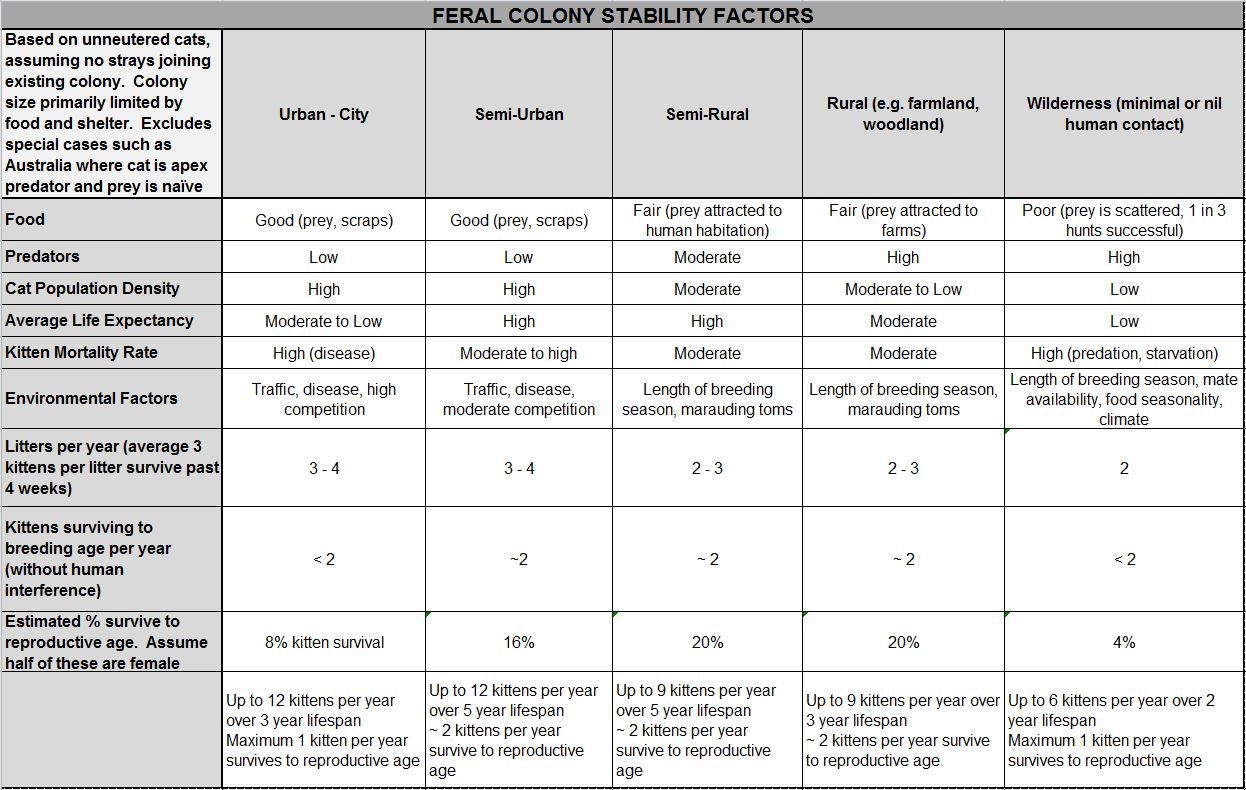

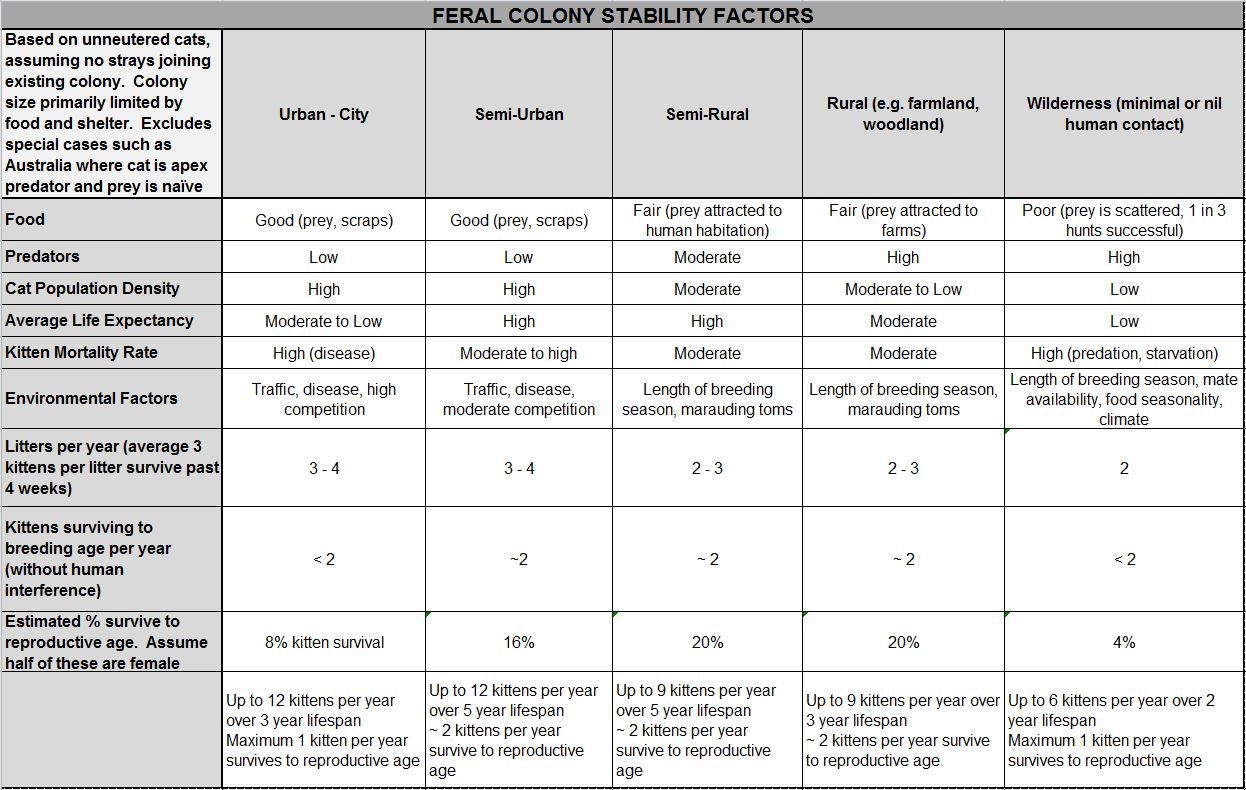

The extermination strategies are enthusiastically supported by those who view ferals as nuisance animals. However, extermination isn't simple or straightforward and is often counter-productive. No eradication method is 100% effective in eliminating cats from large areas and cats which evade the exterminators breed several times a year depending on climate and available food/shelter, quickly re-colonising the area. Cleared areas have under-utilized food sources which attract new cats from outside. The only way to keep an area cat-free is to remove food sources (edible refuse, prey species, handouts by cat-lovers), something which is often impossible or impractical.

Feral extermination has been tried - and failed - in other countries. No method is 100% effective in eliminating cats especially in large areas (such as the Australian continent). Cats which escape breed 2 to 4 times a year, averaging 4 kittens per litter, quickly re-occupying areas where there are food sources. The only way to keep an area cat-free is to eliminate the food sources e.g. edible refuse and all prey species (both native and naturalised). The aim of eradication is to allow wildlife numbers to recover. However, complete removal of cats will also lead to population booms in rabbits, rats, mice, pigeons and other pest species which compete with, or prey upon, desirable wildlife species.

In Australia, there is conflicting 'information' about damage done by cats. Some authorities say that cats are decimating wildlife. Others say that cats are scapegoats as over-clearing and overstocking of land in the late 1800s and the introduction of foxes for sport in 1910 has had a worse impact on wildlife numbers. Observation of hunting bush-cats suggests that they prefer rabbit or pigeon and the study conducted by Reark research for Petcare Information and Advisory Service indicated the cat's preference for hunting introduced species (rabbits, mice etc). Habitat destruction causes native wildlife to decline while the more adaptable cat readily exploits the man-made niches. If cats had done even a quarter of the damage claimed for the past 200 years, there would be no small native animals of any description left in Australia!

Methods used for eliminating strays/ferals around the world have included trapping, poisoning, shooting and viral agents. These are short-term solutions only and may be equally dangerous to wildlife.

In 1992, at a cattle station in the South Western Australian outback Professor J Pettigrew (University of Queensland) shot 175 ferals in a 10 sq km area. The army shot 400 more in 3 days yet a few weeks later they returned to shoot another 200. According to Professor Pettigrew cats were pouring into the vacuum created by the extermination program.

Morialta Reserve (Australia) reported that the cat population had actually grown since culling. The survivors had bred and their offspring were too crafty to be shot or trapped! Some Councils which have attempted feral extermination have simply created populations of fitter, craftier ferals. In contrast a C.A.T.S. (Cats Assistance To Sterilise) study found that the trap-neuter-return of cats in 84 colonies led to an overall reduction in cat numbers: unneutered cats were no longer attracted to colonies and no kittens were born to replace cats which died. The resident populations deterred other cats which would have swarmed into an area vacated by an extermination method.

The use of viral agents is ineffective in the long term. The deliberate myxomatosis epidemic in the UK caused a temporary drop in rabbit numbers and killed many pets. Inevitably, some rabbits survived. With less competition for food they bred quickly and passed their immunity on to their descendents. The result? A population more resistant to the virus! A virus cannot distinguish between ferals and pets. Some cats do not develop good immunity after vaccination, others are allergic to vaccines and cannot have booster shots while some owners, no matter how caring, cannot afford vaccinations as well as neutering, so pets would also be infected and die. It is naive to believe that a deliberate epidemic would have any long-term impact on the feral cat population.

Viruses can also mutate and cross from one species to another. A form of canine distemper has been blamed for seal deaths in the Northern Hemisphere. Canine distemper is also killing African lions. The Law of Perversity means that a cat-specific virus would probably pick this very sensitive time to mutate and decimate native animals.

Poisoning is very indiscriminate; the death of countless native animals from poison laid during a mouse plague showed that the impact of cats on wildlife is overshadowed by the impact of our own indiscriminate killing methods. Faddy eating habits can help cats avoid poisons while native animals succumb.

A recent Australian development is FTC2, a cat-specific toxin, which interferes with oxygen take-up and causes death through oxygen deprivation (suffocation). The chemical is claimed to be harmless to Australian native animals (it could not be used in countries where there are wild species of cat). The cat ingests a poison bait, becomes unconscious and then dies. It is claimed that cats which consume a sub-lethal dose will regain consciousness and suffer no lasting ill-effects. There is no information about a specific antidote for the poison should a pet cat ingest a lethal dose and it has been claimed that it will be used areas well away from pet cats (the vacuum effect applies). The Australian RSPCA have not opposed the use of FTC2 as it is proven to kill in a humane way.

Where a poisons are used, individual poison-resistance occurs due to continued low-dose exposure to a poison. In fast-breeding creatures, poison-resistant individuals occur through mutation. Often poison-resistant individuals already exist and simply take advantage of reduced competition for food and space. When they breed, they pass on the poison-resistant trait and resistant individuals eventually outnumber susceptible individuals (as with disease resistance e.g. myxomatosis). If FTC2-resistance is not allowed to develop then the use of species-specific poison offers a humane, medium term solution and may reduce numbers to a level manageable by other means.

Steel-jaw traps are very hit-and-miss as fur trappers already know. Non-target animals, including pets, rare or endangered animals, fall victim to traps and snares. This method can do more harm than the trappers' target animal. Box-trapping and euthanasia sounds humane and effective, but is tedious and consequently costly work. The only people with the patience to continually check traps tend to be cat workers whose love for cats endows them with the infinite devotion to duty needed for such a mammoth undertaking. Less conscientious trappers may simply leave trapped animals to die of dehydration or starvation to save effort or the cost of destruction. There will always be cats too cautious to be trapped.

Wholesale killing by any of these methods is inhumane; some of the cats killed would have been feeding kittens which face a slow death through starvation or by being eaten alive by ants, insect larvae, rodents or small carnivores (most aren't fussy about the prey being dead or alive, just so long as it doesn't fight back). All eradication methods have the same, well documented, outcome: the vacuum effect. 'New' cats flock to the vacated area to exploit whatever food source attracted the original inhabitants while survivors breed and their descendants are more cautious or more disease resistant.

Indiscriminate methods also result in the death of pet cats; collars are not always visible at shooting range and traps, poisons and biological agents cannot distinguish between pet cats and strays/ferals. There are people happy to kill pets and ferals indiscriminately (using 'wildlife protection' as a convenient excuse for existing sadistic tendencies), especially if they can gain kudos for each kill.

What about proposals for controlling pet cats? Judging from the effects of Britain's Dangerous Dogs Act (compulsory neutering and registration), compulsory registration would prove counter-productive. Some owners cannot afford registration fees or subsequent fines. They would keep unregistered cats which then have no legal access to vet care such as neutering. Cat legislation could lead to bureaucratic injustices and bully tactics by local Councils against citizens. In Australia, the Reark Survey concluded that compulsory neutering, registration and curfew are unenforceable. The cost would be prohibitive and the measures would cause worse animosity between cat lovers and Councils. It would only affect urban cats which pose less of a threat to native fauna for the simple reason that there is less native fauna in urban areas, but it would have little effect on stray/feral populations.

Note: C.A.T.S. is currently the only organisation in Australia involved in long term studies of the "Sterilise and Return to Home" (Trap-Neuter-Return) method of controlling feral colonies. Trap-neuter-return is the only long-term effective method of controlling feral populations.

FERAL ERADICATION - IMPOSSIBLE TO ACHIEVE

Does extermination of stray/feral cats really protect wildlife? There are those who genuinely believe that the only way to protect wildlife is to completely remove cats from the environment. Yet throughout the world extermination has been proved either impossible or counter-productive. No method is 100% effective in eliminating cats from areas such as parks and any suddenly under-utilised food supply attracts new cats into the area. Many eradication methods also kill the very animals anti-cat activists want to protect - completely counter-productive to their declared aims.

Throughout the world there are conflicting views on ferals. Some view them as beneficial animals, controlling vermin - many farms "employ" cats for this reason. From the days of ancient Egypt ferals have been "employed" to control vermin. Their presence may give pleasure to people who enjoy watching them, although some misguided "carers" disagree with neutering ferals because they enjoy seeing the kittens (90% of which die in their first year). Others view ferals as health hazards (spraying, unburied faeces), vectors for zoonotic diseases, general nuisance (caterwauling, raiding garbage), predators upon wildlife/gamebirds or simply as an inconvenience.

Although it is claimed that ferals decimate wildlife, there is a strong counter-argument that cats are scapegoats for human activities e.g. land clearance and habitat destruction. As humans need more space, land available for wildlife decreases. Built-up areas and artificial barriers prevent the migration of wildlife from an exhausted area to new territory. What native animals regularly and effectively prey upon rodents and rabbits which can do serious damage to both habitat and native wildlife numbers?

In Britain, ferals are viewed as a nuisance by gamekeepers afraid for their pheasant stocks and by some farmers. Gamekeepers are primarily concerned about keeping the population density of game birds such as pheasants unnaturally high to keep shooters happy since many pheasants are shot for sport not food. To protect stocks, gamekeepers kill native British wildlife (the domestic cat is not native to Britain) including weasels, crows, protected birds of prey such as Kites and protected mammals such as the native Scottish Wildcat. Domestic cats found in the wrong place have fallen foul of gamekeeper's guns.

While feral cats are welcome as vermin controllers on some farms, other farmers sometimes ask rabbit shooters on their land to shoot feral cats. One farmer even organised a "feral-shooting party". Pet cats living near such farms have gone missing or returned with shotgun injuries or trailing rabbit snares. One pet cat returned home 'almost cut in two' by a rabbit snare which had tightened just below its ribcage. Urban ferals are considered pests on hygiene or nuisance grounds.

In Australia, where the cat/wildlife debate is strongly polarized, cats are generally believed to have been introduced by European settlers, although Aboriginal peoples have claimed that cats were present prior to the settlers' arrival. The cat is a convenient target for hatred since it is an obvious hunter. Factors such as overclearing and overstocking of land, clearing of land for development and the deliberate introduction of other alien species are rarely considered. Studies indicate that the cats prefer to hunt introduced "pest" species (pigeons, rabbits, mice etc) and in Tasmania the feral cat co-exists with the marsupial "Native Cat".

In San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, US, ferals were blamed for the decline in the park's songbird population. A 1992 article in the San Francisco Chronicle blamed the cats, but citizens who fed both cats and birds, some for over 20 years, disputed this. The songbird decline coincided with a park landscaping programme which had removed undergrowth needed by the birds for food and habitat. Predators rarely overbreed to a point where the food supply is too depleted to support the predator population. The supply of prey (and food scraps) limits the number of predators in the area.

Many of the Golden Gate Park cats had been neutered. By removing them, Park authorities encouraged other cats to move in and begin their breeding cycle in the vacant ecological niche; a potential population explosion. Similar situations arose at Riverside Park, Virginia, US, where the cats were perceived as a threat to wildlife and the Gillis W Long Hansen's Disease Center, Louisiana, US, where they were considered a health hazard. In Louisiana the problem was complicated by the fact that patients enjoyed seeing the cats and ignored regulations forbidding them to feed the cats. At Riverside Park, cats were trapped and destroyed during the Spring breeding season despite public opposition. Trapped cats included lactating females. Dead and dying kittens were subsequently found in the park, yet the trapping programme was supported by some major humane societies despite the obvious and unnecessary suffering it was causing.

Marion Island, south-east of South Africa between Antarctica and South Africa, is a small inhospitable island (approx 20 km x 13 km [ 12 miles x 8 miles] = 30,000 hectares). In 1993, after a 16-year battle, more than 3000 feral cats have been eradicated from Marion Island. It is believed to be the first time that so many cats have been eliminated from an island of this size. It took 16 years of cost and effort to eradicate 2,500 (lower estimate) to 3,400 (higher estimate) cats from a small island where teh vacuum effect could not occur

In 1949, a group of scientists left the island, leaving behind 5 unneutered cats. By 1975 there were 2,200 - 2,500 cats on the island preying on ground-nesting seabirds. The population was increasing by an estimated 23% each year. By 1977, there were an estimated 3,400 cats. Deliberate infection with feline enteritis killed around 65% of the cats but the remaining 35% developed an immunity to the disease and continued to breed. By 1982, there may have been as few as 620 surviving cats, all immune to the virus and breeding further generations of immune cats.

Jack Russell Terrier dogs were used to flush out the remaining cats and between 1986 and 1989 further cats were exterminated by hunting. 897 cats were shot. It still required traps with poison baits to eliminate those cats which had eluded the dogs and guns. There appears to be no information on how many seabirds ate poisoned bait and died themselves. No cats have been seen since 1991 and in 1993, the programme was declared a success. Eradication programmes can only succeed in relatively small and geographically isolated areas. On the mainland, the area would quickly be flooded with cats moving into the vacated area.

In the English village of Boreham, residents wanted the feral population reduced drastically or eliminated completely. Despite regular trapping and removal by animal welfare groups and pest-control firms, the village's feral population always returned to its previous level. Ferals from neighbouring areas moved into the vacated area along with unneutered pets and strays. After 10 years of repeated trapping, Boreham's feral population was larger than ever. A few residents agreed to maintain stabilized neutered colonies and these repelled incomers from other areas, but wherever cats were removed completely, new breeding colonies quickly established themselves.

Elsewhere, a Post Office used poison against feral cats. The poison bait was also eaten by hedgehogs (beneficial insectivores) and various insectivorous birds. Similar programmes to control pigeons on farmland by using poison grain killed many protected birds of prey which ate poisoned pigeons. The poison also killed small carnivores (e.g. hedgehogs, weasels) and carrion-eaters which ate the carcasses of poisoned birds. Inoffensive seed-eating birds who viewed the dumped poison grain as manna from heaven also died. The use of poison caused long-term damage to some bird populations and pushed some already endangered species close to extinction.

The feral cat population on Ascension Island increased dramatically during the Falklands War, when the island became an important military base. The cats have been responsible for the extinction of several species of seabird, which they have hunted for food. In 1993, a cat culling programme removed about 400 cats, but ran into difficulties because limiting the cat population allowed rats to increase. The rats caused as much damage to seabird populations as the cats had done. There were suggestions of not merely controlling the population, but eradicating it altogether. Culling could affect owned domestic cats and eradication would allow the rat population to explode.

In 1994, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office asked the Royal Society for the Preservation of Birds (RSPB) to visit the island and report back, allowing a suitable strategy to be formulated. The RSPB is experienced in the matter of rats and cats, but many members are rabidly anti-cat and there were fears of a report biased against any form of cat ownership on the island. Ascension Island offers a small-scale version of the Australian cat problem - cat hunt both native animals and introduced ones (in this case, rats); removal of the cats allows the rats to breed unchecked and the damage to native animals continues; removing the rats means the cats must eat more native animals. Both introduced species must be managed in parallel.

In an areas as large as Australia or the United States, eradication is an impossibility. In 1992, at a cattle station in the South Western Australian outback, 175 ferals were shot in a 10 sq km area. The army shot 400 more in 3 days. A few weeks later they shot another 200. The original cats had been killed, but the food supply which had supported them remained. New cats poured into the vacated area to take advantage of the suddenly unexploited resource and the population density actually increased overall.

The vacuum effect which follows culling can result in the area becoming more densely populated with cats. In where the vacuum effect is impossible, a single breeding pair is all it takes to replenish the cat population - the availability of unexploited food resources increases the cats' breeding success.

The whole issue of eradication is an emotive one, not least because of the methods used against cats.

On Marion Island viral agents were only partially effective yet such a method was recently backed by South Australian MP Peter Lewis as a way of killing off Australian ferals in the same way that myxomatosis was used against rabbits (successful in the short term, disastrous in the long term). Poisoning is indiscriminate.

Steel-jaw/leg-hold traps are designed to hold an animal without killing it outright. Humane groups monitoring their use found that the traps maim the victim (shattered leg-bones, tissue damage). Such traps are not selective and also injure protected wild animals and valuable livestock, usually necessitating the destruction of the victim. I understand that a WIRES representative obtained photographs of native Australian animals caught in traps. Back-break traps which are intended to kill the victim cannot distinguish between the target animal and non-target animals animals which are attracted to the bait. Because back-break traps are designed for specific species, a non-target animal can suffer horrendous injury, but not be killed. Wire snares indiscriminately trap and strangle any suitable sized animal which blunders into it, including native wildlife. Those who seem unconcerned about the humane aspects of traps should consider the fact that using them is totally irresponsible from a wildlife protection point of view.

Box-trapping is humane if carried out by conscientious groups, but is open to abuse by those who are anti-cat. Lactating cats should be freed for humane reasons (unless the kittens are also collected), domestic pets should also be freed as should wild animals which become trapped (hedgehogs are particularly attracted to cat food and are heavy enough to spring the trap). Less conscientious trappers may simply leave trapped animals (regardless of species) to die of dehydration or starvation to save effort or euthanasia fees.

A number of years ago it was reported that feral cats were being trapped in part of Japan. Anyone finding a trap containing a cat was forbidden to release the animal or to provide food or water for the cat's comfort prior to collection and euthanasia. It was alleged that many cats were left to die of dehydration in the traps. Traps may be sprung by wild animals attracted to the bait so they must be checked and reset frequently.

Shooting is possible if carried out by a trained marksman. Untrained individuals may injure rather than kill and may misidentify prey. It is impossible to distinguish a feral from a wandering pet at a distance though shooting may be the only safe method if the cat is rabid. Another utterly distasteful method is clubbing. I have been told that feral cats and kittens are killed by clubbing on a certain private golf-course in Essex although hard evidence is impossible to obtain (brain damaged cats and kittens from that location have sometimes been found in nearby gardens and taken to rescue shelters).

One aspect of eradication rarely given a second thought by those who want colonies removed, is what happens to the trapped cats. Many members of the public seem to think that the cats are transported to some farmyard paradise and let loose. Some have even asked pest control operatives "how the trapped cats are doing" and are horrified to learn that the cats are not happily living out their days on Old MacDonald's farm, but were destroyed. There is the risk that the method of "en masse euthanasia" used when large numbers of cats are trapped are the least costly, fast-throughput methods, not the most humane ones.

The method of euthanizing large numbers of cats is a cause for concern to many people, who feel that the chosen method may be based on speed and cost, not on humane grounds. Mass extermination by decompression, as used in some American states and some oriental countries, causes distress. Chloroform (used in chloroform chambers) is an irritant and can cause a distressing "pre-anaesthetic excitement phase" while electrocution is inhumane as the cat's skin has a high electrical resistance. I have received letters from Australian cat-lovers and cat-workers distressed by the shooting of cats and kittens in crush machines at council depots. Even in animal-welfare-conscious Britain some rural people still prefer to drown excess cats by the sackful.

Many anti-cat lobbyists spare little thought for the distress caused by such "fast-throughput" methods. Such methods create antipathy among animal lovers. Many of those who feel that ferals numbers need to be reduced believe that it should be done humanely and selectively.

Eradication, by whatever method has been sanctioned, almost always leads to the vacuum effect, small islands excepted, or to populations of craftier, more disease-resistant cats. What is needed is a humane, long-term approach to feral control. Aside from those small island locations, eradication has always proved unsuccessful. With food available, the cats soon attain their former numbers so "eradication" is only a temporary fix. What is needed is a long-term approach to the problem of ferals.

In some places, ferals are fed by cat-lovers (who derive genuine enjoyment from caring for feral colonies) who cannot understand why "their" cats are viewed as a problem by other people. Residents opposed to a large colony of scavenging cats displaying all the antisocial problems associated with unneutered cats might be amenable to a smaller resident colony of neutered cats which are fed in specific areas and which do not spray, fight, caterwaul, midden or breed. Those opposed to seeing tatty, scrawny strays (on either aesthetic or welfare grounds) are often surprised to find that neutered ferals are healthier and have less impact on wildlife due to the cessation of breeding..

Those who, quite reasonably, won't tolerate a teeming mass of thirty unneutered cats might find a stable resident colony of twelve neutered cats acceptable. The chances of this sort of a compromise might be increased if it is explained that the cats are not going off to some rural idyll, but will most likely be put to sleep.

How can a colony be reduced in size? Most colonies will contain cats which are FeLV/FIV positive, ill, injured or suffering from the ravages of age. For these, euthanasia is the kindest option. Feral cats are not co-operative patients and resent being kept captive while they are treated. Some cat sanctuaries have large enclosures with sheds, chalets and enough space for such cats to live semi-free lives, but there are always more cats than there are spaces at such sanctuaries and sanctuaries offering adequately sized enclosures which aren't overcrowded are few and far between. Other cats in the colony may be tame strays which are homeable, there may be tameable kittens or even a local landowner who actually wants to acquire some neutered ferals. The healthiest cats are the ones which should be neutered and returned to site as these have the best long-term chance of a decent life.

In contrast to the problems in San Francisco, Virginia and Louisiana, ferals in Longwood Gardens, Pennsylvania, US, were trapped, neutered and released and provided with litterboxes and shelters. At the same time, efforts were made to preserve or increase bird habitats in the gardens. Despite the presence of the cats, the bird population, including ground-nesting species, has increased. The cats themselves are an added attraction with visitors.

In Australia, the neutering of cats in studied colonies led to an overall reduction in cat numbers since the resident cats deterred outsiders which would have swarmed into a vacated area and no kittens were born to swell numbers. The few cats which did join the managed colonies could be identified, trapped and neutered or rehomed if found to be tame.

Eradication methods, even if implemented in the most humane manner possible, cannot solve the feral cat problem. They are frequently unpopular with the public and at best they are only temporary fix. Trap-neuter-return programmes may be time-consuming and seem like a drop in the ocean, but offer the best hope of a long-term solution to the cat population problem, giving healthy ferals the chance of a decent life and freedom from the otherwise endless cycle of breeding while those which cannot be re-released should at least be given a humane and painless escape from their predicament.

CAT CONTROL IN OTHER COUNTRIES

Around the world different countries have developed various regulations and approaches to feline welfare and population control. By giving pet cats more value and by encouraging or mandating neutering, these countries aim to reduce the number of cats joining the feral population each year. In addition, the stray and feral problem needs to be tackled. The feral problem cannot be effectively tackled unless the pet overpopulation is addressed.

AUSTRALIA:

Until the 1990s cats had no legal status in Australia. The Australian RSPCA advocated controls such as limiting the number of cats per household, registration fees (dual price system with discounts for neutered cats), penalties for cats which injured wildlife, and protocols for impounded and unclaimed cats. In 1992 the Sherbrooke Council in Victoria introduced cat curfews, compulsory registration, identification and neutering. In 1996, the Domestic (Feral and Nuisance) Animals Act aimed to address problems of registration and identification, establish appropriate neutering programs and procedures to be used in trapping, impounding, housing and disposing of strays. Additional goals included education and encouraging responsible attitudes to pet ownership. After the Act was implemented, the RSPCA reported that the number of cats destroyed in Australia dropped by 5% per year. In 1999 the Companion Animals Act required all cats born after July 1 1999 to be microchipped. Today all animals sold by the RSPCA, Animal Welfare League and Cat Protection Society are microchipped . To encourage neutering, registration fees range from Aus$35 for neutered animals to Aus$100 for unneutered animals. Councils have the power to establish cat-free zones, impound strays and enforce a cat curfew if complaints are received from anyone angered by roaming or hunting cats.

Figures for the number of feral cats in Australia vary from 5 to 18 million. The National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) considered the use of poison baits or deliberately introduced diseases such as feline enteritis but these methods were met with great opposition. A cat-specific toxin has now been developed and is considered humane for use against feral cats in remote areas (where pet cats are not present). The strategies for dealing with unclaimed or un-microchipped cats vary between organizations. Cats taken to municipal pounds are usually put down immediately. The RSPCA waits 3 days.

There are moves in Australia towards subsidised neutering, compulsory registration and public education on responsible pet ownership as well as towards methods for culling feral cats in order to protect a fragile ecosystem already damaged by human interference.

NEW ZEALAND

Like Australia, New Zealand is an island (2 islands) onto which cats have been introduced by humans. There is concern about feline predation upon bird species and about the pet and feral cat population. City Councils help to fund local SPCAs to control the feral cat population. For example, Nelson City Council give NZ$8000 a year to the SPCA for the purpose of feral cat management.

Cat registration schemes have been proposed as a way of controlling the cat population. In 2002 Nelson City Council heard proposals for a cat registration scheme. It was rejected on grounds of cost. It costs the city NZ$250,000 per annum to run the dog registration scheme for 4000 (approx) dogs. With an estimated 11,000+ cats in the area, the cost of a comparable registration scheme was prohibitive. Instead, it residents would be urged to bell their cats and educated about the predation problem.

Anti-cat feeling exists in parts of New Zealand. In response to the rejected proposal for cat registration in the City, two Councillors advocated a "cat day" - a day on which locals go round shooting all the strays (in East Borneo there are "dog days" - a day-long open season on stray dogs). Another Councillor suggested that people could even be encouraged to eat cats, again based on the eating of dogs in other countries.

SINGAPORE:

In Singapore the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority is responsible for all matters relating to domestic animals. Previously the large stray cat problem in Singapore was controlled with culling but this proved to be inhumane, as well as ineffective and costly. In 1997 the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority implemented the Stray Cat Sterilisation Project whose key objectives include sterilisation and responsible cat management. The SPCA, Cat Welfare Society (CWS), veterinary clinics and volunteers trap, sterilise, identify and attempt to re-home stray cats from residential areas. There are also a number of concerned individuals and local non-profit organisations involved in rescuing and rehoming cats and working with feral colonies in their immediate area.

In 2003, feral cat work in Singapore was badly hit following the SARS outbreak. Incorrectly attributed to cats, SARS is a serious flu-like illness carried by Palm Civets, a type of mongoose sometimes erroneously called a Civet Cat. This was used as the rationale for rounding up and exterminating stray cats on Singapore for "hygiene reasons". Even controlled (neutered) feral colonies were not exempt from the deadly round-up. I am advised that tough anti-littering laws in Singapore also makes life difficult for feral cat carers. Although it is not against the law to feed stray cats, there are tough penalties for littering. Feral cat carers must therefore find ways to feed cats without falling foul of anti-litter laws.

UK:

The United Kingdom has a large unwanted cat problem with over a million stray/feral cats. It is up to small independent charities to raise funds for cat welfare, trapping, sterilisation, re-homing and care of cats in their area. There is no overall control of cats. The Feline Advisory Bureau published the Cat Rescue manual to provide advice on feral cat sterilisation schemes and shelter for rescued cats. There are several non-profit organisations who work primarily with feral cats e.g. Cat Action Trust. In recent years, a number of other societies, primarily The Mammal Society, have pursued very public anti-cat campaigns which rely heavily on statistics extrapolated from small, unrepresentative samples of cat and human populations. These poorly conducted surveys have received disproportionate attention from the popular press while more scientifically conducted studies have received little or no coverage. This has promoted antipathy towards pet and feral cats alike.

Under the UK law, feral cats belong to the land owner and may be shot, or trapped and destroyed in a humane manner though illegal methods are frequently used and there are a number of prosecutions each year when pet cats fall victim to illegal methods. There is a strong emphasis is put on trapping, neutering and returning ferals to produce stable managed colonies and avoid the vacuum effect. Britain also has an indigenous species of cat which is endangered through interbreeding with domestic cats. Urban stray and feral cats are considered a nuisance on health and hygiene grounds and may legally be removed and destroyed by pest control agencies. In some cases, licenses have been granted for the use of poison against feral cats.

An estimated 10% of cats are indoor-only pets, but this percentage is increasing, primarily to protect cats from outdoor risks such as traffic. Declawing is not permitted unless there are very exceptional grounds.

CANADA:

In Canada, the municipal government, the veterinary association, and various animal welfare organizations are responsible for cat management. Historically, cats were allowed to roam freely in cities, but due to the increasing cat population and increasing complaints, the Canadian Municipal government passed cat control bylaws. These require cats to be licensed, permanently identified, and kept indoors or allowed out on a leash (I have seen several leashed cats being walked in Quebec). Bylaws vary, but the following is an example. Cat owners must register their cats from 4 months of age; cats are required to be on a harness or a leash when outside their property. Failure to comply results in a fine or impoundment of the cat. There is a dual-price licensing system e.g. Can$15 (neutered) compared to Can$50 (unneutered). The fee for retrieving an impounded cat is halved if the cat is neutered.

The Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) offers professional advice about ethical issues and guidelines for cat management for example CVMA members believe that declawing makes cats more manageable and should be performed on domestic cats which are at risk of being denied a home or face euthanasia. This is in line with a move towards a primarily indoor lifestyle for cats.

The Canadian Federation of Humane Society (CFHS) is a non-profit organisation which provides shelter and husbandry services for stray cats across Canada. One of the registered members of this CFHS, the British Columbia SPCA, works with the Correctional Service of Canada to arrange inmates to care for abandoned cats, an arrangement beneficial for both the cats and the inamtes.

HONG KONG:

Cat management is of less concern in Hong Kong in comparison to the other countries mentioned. The Veterinary Surgeon Board, a sub-branch of the Hong Kong Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, is responsible for animal licensing and quarantine services. There are strict restrictions on animal trading and boarding from other countries, but little in respect to cat licensing and feline management guidelines.

Cats in Hong Kong roam freely on the street and are blamed for the spread of disease, including the deadly "chicken-flu" of 1998. There are individual non-profit organizations e.g. ShaTin Farm, which provide shelters and food for injured or abandoned cats from the city. There is also a veterinary clinic staffed by overseas vets (e.g. British, Australian) offering a much-needed service to responsible pet owners in Hong Kong.

FURTHER READING:

Feral Cats: Suggestions for Control, UFAW Publications.

Practical Guide to Working with Feral Cats, Anne Haughie, FAB Bulletin Autumn 1991, Vol 28, No 2.

Resiting Feral Cats, Anne Haughie, FAB Journal Winter 1992, Vol 29, No 4.