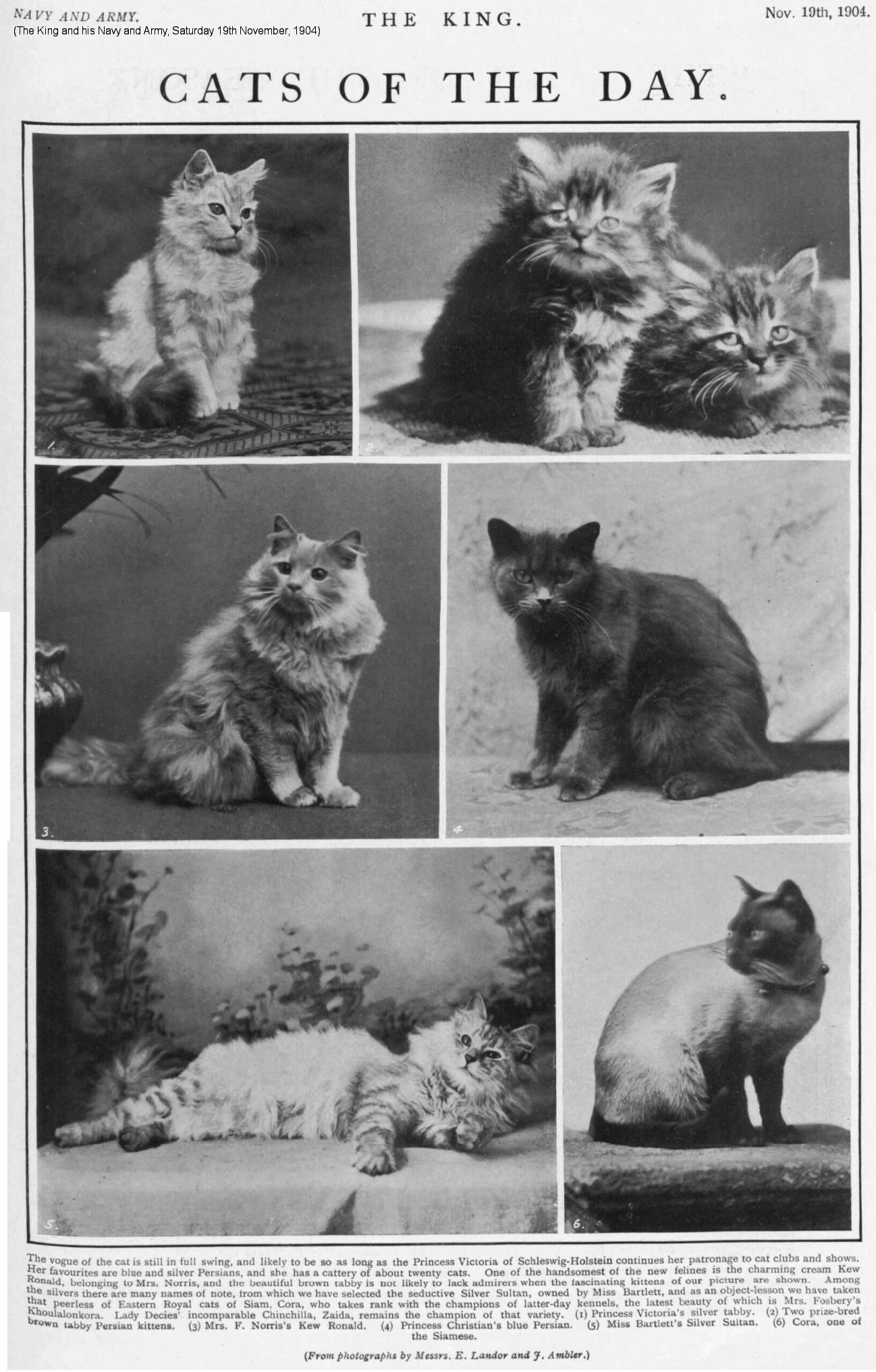

CATS AND CAT CARE RETROSPECTIVE: 1900s - 1930s: BREEDS AND VARIETIES:LONGHAIRS, BRITISH SHORTHAIRS, MANX AND DIVERSE BREEDS IN BRIEF

This article is part of a series looking about cats and cat care in Britain from the late 1800s through to the 1970s. It is interesting to note how attitudes have changed, as well as how our knowledge has increased.

The following brief survey of the feline world was written by LOUIS WAIN, probably in the early 1900’s and was later reprinted in “Our Cats” after being found as a magazine cutting.

SIAM sends us a regal animal in the Siamese Royal Cat; it has a brown face, legs and tail, a cream-coloured body, and mauve or blue eyes. The Siamese take great care of their cats, for it is believed that the souls of the departed are transmitted into the bodies of animals, and the cat is a favourite of their creed; consequently the cats are highly cultivated and intelligent, and can think out ways and means to attain an end.

The Sand-coloured cat, with a whole-coloured coat like the rabbit, which we know as the Abyssinian or Bunny Cat, is a strong African type. On the Gold Coast it comes down from the inland country with its cars all bitten and torn away in its fights with rivals. It has been acclimatized in England, and Devonshire and Cornwall have both established a new and distinct tribe out of its parentage. The Manx cat is nearly allied to it, and a hundred years ago the tailless cat was called the Cornwall cat, not the Manx. I have not yet seen a Bunny Long-haired.

White Cats I might call musical cats, for it is quite characteristic of the albinoes that noises rarely startle them out of their simpering, loving moods. The scraping of a violin, which will scare an ordinary cat out of its senses, or the thumping of a piano, which would terrorize even strong-nerved cats, would only incite a white cat to a happier mood. Certainly all white cats are somewhat deaf, or lack acute quality of senses; but this failing rather softens the feline nature than becomes dominant as a weakness.

The nearest to perfection perhaps, and yet at the same time extremely soft and finely made, is the Blue Cat, rare in England as an English cat, but common in most other countries, and called in America the Maltese Cat— for fashion’s sake probably, since it is too widely distributed there to be localized as of foreign origin. It is out in the mining districts and agricultural quarters, right away from the beaten tracks of humanity, where the most wonderful breeds of cats develop in America. Caravan showmen have told me that at one time it was quite a business for them to carry cats into this wilderness, and sell them to rough, hardy miners, who dealt out death to each other without hesitation in a quarrel, but who softened to the appeal of an animal which reminded them of homelier times.

One man told me that upon one occasion he sold eight cats at an isolated mining township in Colorado, and some six days’ journey farther on he was caught up by a man on horseback from the township, who had ridden hard to overtake the menagerie caravan, with the news that one of the cats had climbed a monster pine-tree, and that all the other cats had followed in his wake; food and drink had been placed in plenty at the foot of the tree, but that the cats had been starving, frightened out of their senses, for three days. Despite all attempts to reach them they had only climbed higher and higher out of reach into the uppermost and most dangerous branches of the pine.

The showman hastened with his guide across country to the township, only to find that in the interval one bright specimen of a man belonging to the village had suggested felling the tree, and so rescuing the cats from the pangs of absolute starvation should they survive the ordeal. A dynamite cartridge had been used to blast the roots of the pine, and a rope attached to its trunk had done the rest and brought the monster tree to earth, only, however, at the expense of all the cats, for not one survived the tremendous fall and shaking. A sad and tearful procession followed the remains of the cats to their hastily dug grave, and thereafter a bull mastiff took the place of the cats in the township, an animal more in character with the lives of its inhabitants.

Analogous to this case of travelling menageries, we have the great variety of Blues, Silvers, and Whites which are characteristic of Russia. There is a vast tableland of many thousands of miles in extent, intersected by caravan routes to all the old countries of the ancients, and it is not astonishing to hear of attempts being made to steal the wonderful cats of Persia, China and Northern India, as well as those of the many dependant and independent tribes which bound the Russian kingdom. But it is a remarkable fact that none but the Blues can live in the attenuated atmosphere of the higher mountainous districts through which they are taken before arriving in Russian territory.

It is no uncommon thing to find a wonderful complexity of Blue cats shading to silver and white in most Russian villages, or Blue cats of remarkable beauty, but with a dash of tabby-marking running through their coats. Their life, too, is lived at two extremes. In the short Russian summer they roam the woodlands, pestered by a hundred poisonous insects; in the winter they are imprisoned within the four walls of a snow-covered cottage, and are bound-down prisoners to domesticity till the thaw sets in again.

Many of the beautiful furs which come to us from Russian are really the skins of these cats, the preparation of which for market has grown into a large and thriving industry. The country about Kronstadt, in the Southern Carpathian Mountains of Austria, is famous for its finely developed animals; and here, too, has grown up a colony of sable-coloured cats, said to be of Turkish origin, where the pariahs take the place of cats.

The following guide to the recognised breeds dates from around 1938 and is from the USA; it omits the Abyssinian:

"All cats that are popularly kept as pets fall into two groups, short-haired cats and long-haired. The domestic cats of the United States-the common cats of our homes and high- cats ways-are short haired. Two distinctive varieties, the Manx and the Siamese, are also short haired. The long-haired type includes the Persians. There are fourteen recognized colours, or combinations of colours, for long-haired cats, and the same number for shorthaired cats. Among the domestic short-hairs, and among the Persians, a particular colour will often give a name to a cat, such as: tortoise-shell cats, chinchilla cats, calico cats, silver tabbies, smokes, Maltese (often called "blues"), etc. So a difference in name may not mean a difference in race; the same breed of cats has several names. Only the Siamese has its own individual colour standard.

DOMESTIC CAT: Despite the fact that this cat's breeding may be a complete mystery, the common domestic cat must meet as many standards as the Persians when entering the cat shows. This speaks rather well for domestic pussies, since large numbers of them reach fame by the show route. But more important than possible show rating is the domestic cat's value as a friend and workman. Adversity has given this cat much strength and endurance, and a tough constitution. Probably originating in stock descended from the nearly deified cats of Egypt, the domestic cat today is often a fellow who works for a living. Whether on farm or shipboard, in the United States Treasury or in your own home, this is the cat that plagues the rats and mice the world over. Well cared for in your home it will be as courteous and presentable as any cat with an impressive pedigree.

MANX: This is the short-haired cat without a tail that has become almost as well known in porcelain and bronze as it is in its own lush fur. Good resident of the Isle of Man for many years, the Manx cat has now become so rare it cannot be exported from the Isle. The Manx is an amiable, intelligent cat, one much sought as a companion. However, it is unusual to see one in a home, even in Europe. The Manx never had a tail. Writers have prepared many tales to explain this fact, but it continues to be a mystery. When it runs, the Manx has a gait more like a rabbit than a cat. The Manx is an ideal pet for persons who want a decidedly individual cat.

SIAMESE: Picturesque, formal, this handsome cat is an all weather aristocrat. It is the chosen temple and palace cat of the ruling Siamese class, and takes its name from Siam. The face, ears, feet, and tail are usually a warm seal brown, while the body is a pale fawn colour shading off to cream on the chest. There are blue Siamese, but you won't see one in a blue moon. Perhaps it has been the cat's association with royalty that has inspired in the Siamese a tendency to be demanding and to require more personal attention than other breeds. Basically the Siamese is a competent cat. Sometimes it is a bit vocal, but it has a warm temperament and is as capable of bestowing affection on a human being as any other good variety of cat. Until a few years ago the Siamese was rare in this country; now it has a large following and is seen regularly at cat shows.

PERSIANS: The Persian is the most widely owned variety of "show cat" in the United States. In its present form the Persian represents a cross between the Angora and the Persian of an earlier day. However, since most of the Angora characteristics were dropped in favour of what the Persian had to contribute to the cross in the first place, the name Persian can be honestly continued for this variety. Properly kept, a Persian is a gorgeous pet. Any thought that these luxurious cats are lazy or difficult to keep healthy may be disregarded. The Persian has a sturdy constitution. His one hazard is his long coat of hair which, combined with his habit of self-grooming, may bring about the formation of hair balls in his stomach. Regular care of the Persian's coat will eliminate this danger […]may not make good mousers because this cat takes such Persian pride in its appearance that it will not risk getting dirty in the pursuit of a mouse. "

|

|

|

Other, less common, breeds existed. The Khmer was a French breed recorded since the 1920s and reportedly brought to Paris from Indochina by 2 French servicemen. It appears to have died out in the 1930s although cats known in France as Khmers were described as late as 1966. In some respects (including the story of its origin) it resembled a Birman and in others it resembled a colourpoint Persian.

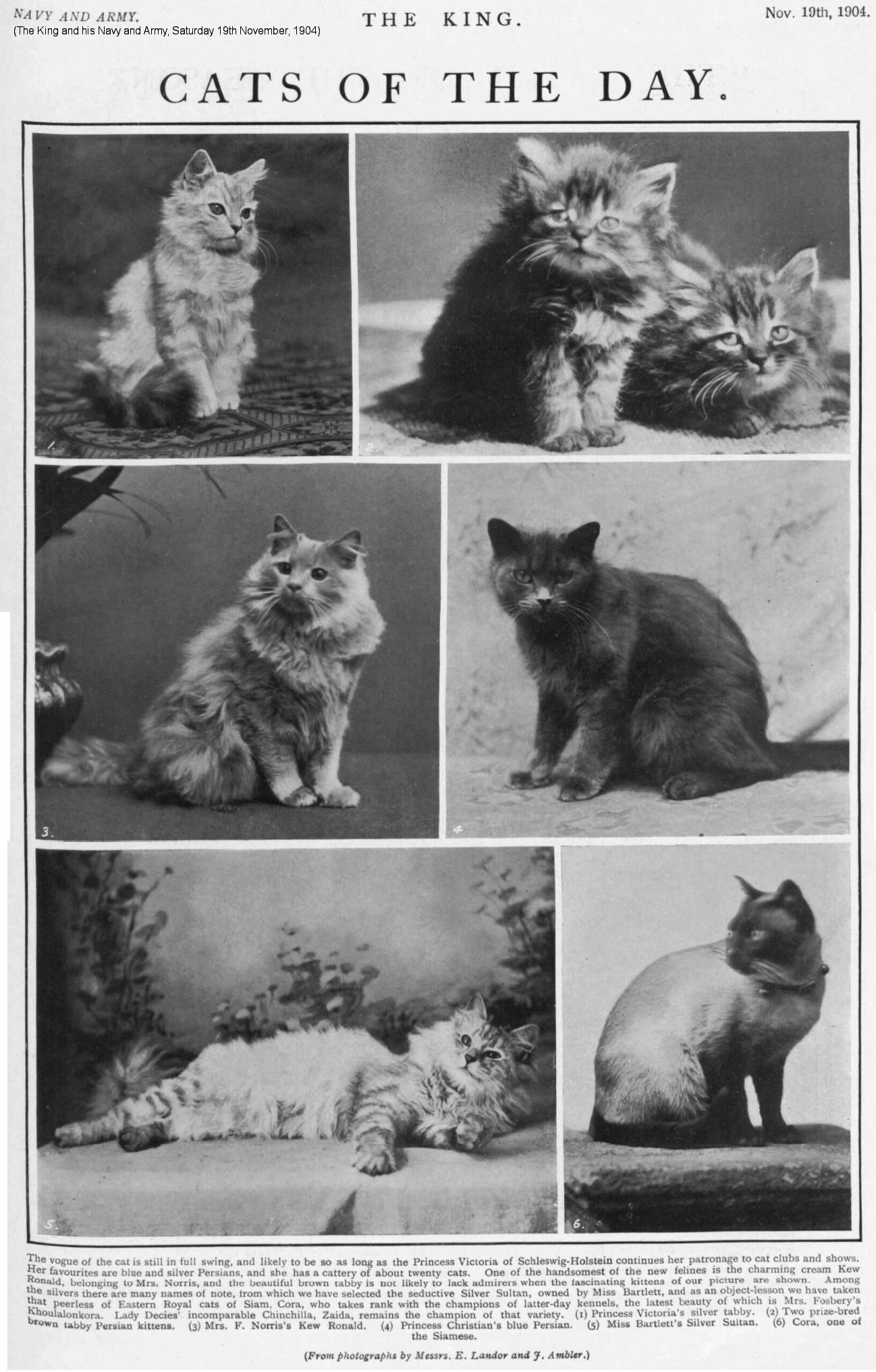

Below is a plate from the "Book of Knowledge" (1935). It refers to "Blue Sapphire" and "Dark Sapphire" as breeds of cat - these appear to be the Blue Persian and the Black Persian.

Persians and Angoras

Persian and Angora Cats were described in “Animal Life and the World of Nature” (1902–1903): "There is no doubt that the Persian cat is the most delicate variety to keep. Perhaps it is that they suffer from good treatment, but whatever be the reason, it is an undoubted fact that they are very liable to attacks of enteric trouble, and those who take a fancy to keeping Persian cats must therefore make up their minds to diet them on sound lines. To begin with it is very undesirable to feed Persians on sweets and dainties; a little raw meat, fish (which must be perfectly fresh), milk, and brown bread which has been made palatable for them by being soaked with gravy - these may be regarded as the staple courses. Of the several varieties of the Persian cat the two commonest are the tabby and the blue. There is a white variety (sometimes called the Angora), and there are various other colours, but on the whole it will be found that the best to keep is one of the quieter colours. They need constant attention to their coats in the way of grooming; but if a comb and soft brush be used regularly and the cat be not allowed to get the hair into a matted condition, this attention need not occupy many minutes a day."

In 1926, Cat Gossip editor H C Brooke noted that at a cat show in Lille there were classes for "Short-hair Persians" (chats persans a poil ras) as well as the normal Long-hair classes. Brooke wondered how "Short-hair Persians" were distinguished from ordinary Short-hairs. In those days, the Persian had not yet become the flat-faced creature we see today and might have been termed a "British Longhair". It later turned out that they were Blue Shorthairs. Due to a misunderstanding, "Persian" was believed to mean a blue-grey cat when cat shows started up in mainland Europe.

Self Brown Shorthair

This snippet on a self brown shorthair is from "Cat Gossip," 29 February 1928: Considering its rarity, we can only regard it as a sad example of the apathy displayed by fanciers to S.H., that the very interesting self-brown exhibited by Miss Harpur at Kentish Town attracted so little attention. We were, unfortunately, unable to see it, though we had heard about it long before, but from all accounts it must be a very interesting and curious cat, and we wish it were our property!

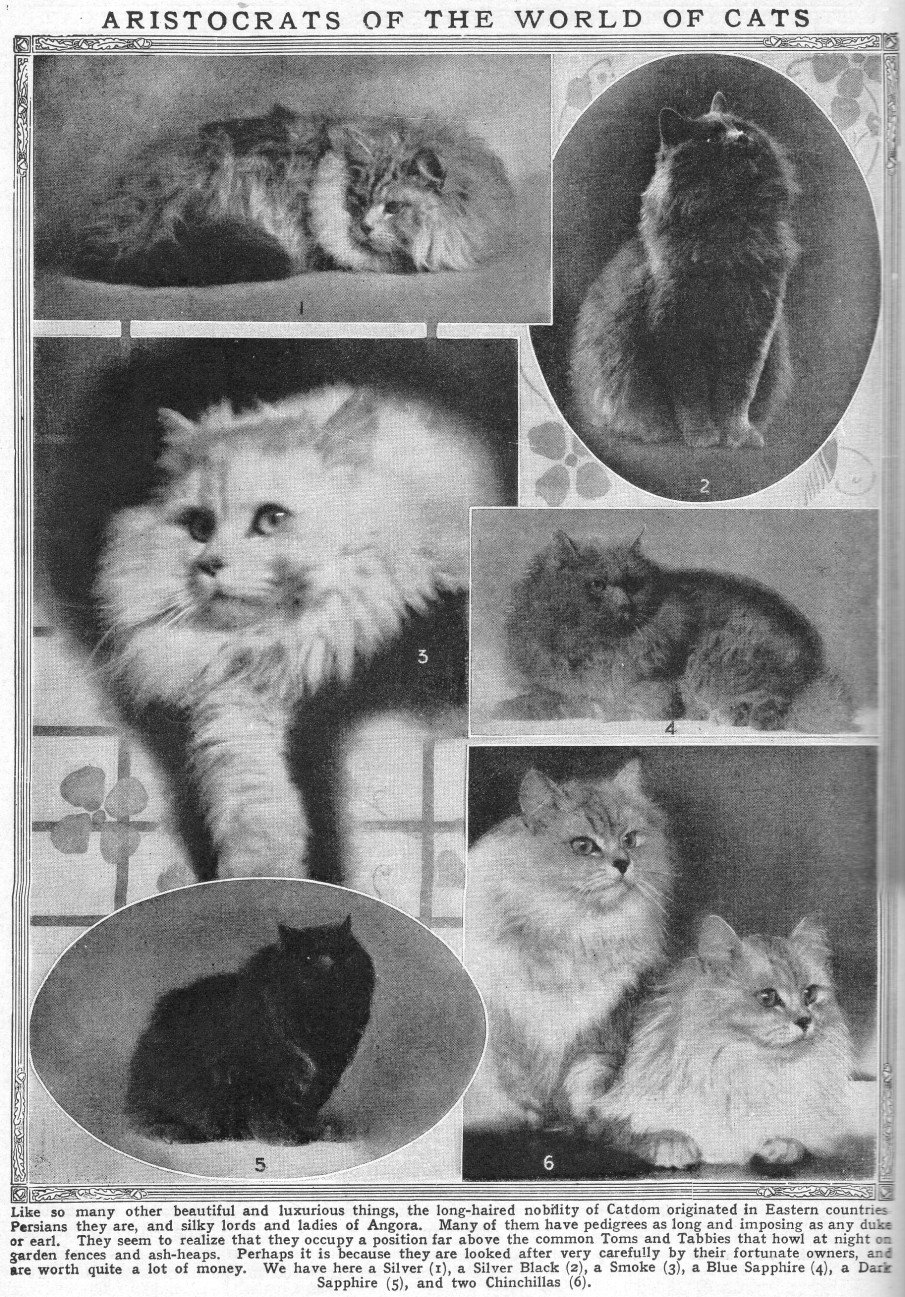

Polydactyle

In the 1920s, there was interest in establishing the “Polydactyle” as a breed. “Cat Gossip,” 22nd May 1929 reports “We have received a most interesting letter from Miss Oldfield Howey, who has for a long time been seeking for information concerning the origin of polydactyle cats. She has recently met a lady who tells her that they are Siberian, and were imported by the Government during the War to fight the rats in the docks, as their large, powerful feet and extra claws were supposed to give them a great advantage over the ordinary British cats, and they were said to be more sporting. The type is a very dominant one, and, once introduced, is difficult to breed out again. Miss Howey has herself proved this to be true, since without any artificial selection it has continually reproduced itself in her cats, since it first appeared in the litter of an adopted stray — not herself polydactyle. Miss Howey’s informant is the owner of a shorthair male, with eight claws on the front feet, obtained from Liverpool docks, and this cat treads heavily, not noiselessly like an English cat, and is a fine ratter. Miss Howey is still thirsting for more details about Polydactyle cats, and hopes that some reader of “Cat Gossip” may be able to tell me whether they were originally long or shorthair, and whether they have any special characteristics as well as the extra claws. Alost of the Polydactyle kittens in her cattery are born with drop ears, and retain them sometimes for weeks, though they eventually take the ordinary form.”

The response from the magazine’s former editor appeared in the same issue: “Mr. H. C. Brooke writes us: “The information given Miss Oldfield Howey as to their origin is erroneous. I doubt if any Government, however foolish, however desirous of squandering the taxpayers’ money, would perpetrate the absurdity of bringing cats from Siberia to a cat-infested country Even if each such cat caught daily three more rats than an ordinary cat, would the purchase be worthwhile? But even assuming, for the sake of argument, that this was done, the origin of these cats would by no means be accounted for. They exist and have existed in all countries. Thirty odd years ago I showed a Manx with all four feet bearing each four extra digits. It is a ‘freak,’ and undoubtedly reproduces itself with some pertinacity. Let us be content with that, and not strive, as has been done, to make out that it is a ‘provision of Nature,' etc., etc., to enable them to take their prey more easily. Were this the case ‘Nature’ would seem rather foolish not to thus ‘improve’ some wild felines, whose existence depends entirely on their power of ‘grabbing.' As a matter of fact, in very many Polydactyles the extra digits are practically useless.

Far more interesting is the fact mentioned by Miss Howey as to the dropped ear. Apparently another freak, which if it only persisted with age would explain to us the legend (?) of the Chinese Drop-Fared Cat, the puzzle of two centuries. No doubt many properties in various animals were originally such ‘freaks’ ; probably the first canine which dropped its ears out of the normal upright position of the canine ear, was so regarded. Polydactylism occurs in the human race, both on feet and hands, but I’ve never heard it suggested this was a provision of ‘Nature’ to enable the human being the better to do this, that, or the other. Such human polydactylism is heritable, as in the cat, but no one has found it so beneficial that they have striven to found a polydactylous strain of humans. The cat, probably owing to its extreme sensibility, seems very prone to ‘freak’ formations.”

I couldn't find any imagesof the proposed breed from the 1920s or 1930s, but I did find one from the 1960s.

Manx

This item “Tailless Cats” is from the Hamilton Advertiser (19th December 1914): It seems probable that the tailless Manx cats came from Cornwall. The managed to survive longer as a distinct breed in the Isle of Man than in Cornwall, the predominance of the common-tailed cat being, of course, aided in the latter district by the fact that, although remote, it is part of the mainland of England, whereas new cats could be carried to the Isle of Man only by sea. The Manx cat which first attracted modern attention was a very different animals from the variously-coloured specimens which now take prizes at cat shows. It was always of the colour of a hare and had fur like a hare. Like a hare, too, it always moved its hind legs together. Its chief food was crabs caught on the beach; and when transported inland from the sea coasts it very seldom, if ever, survived long. No cat of this kind has been seen for many years in the Isle of Man, though there are plenty of tailless cats, its crossed descendants, to be purchased there – Otago “Witness.”

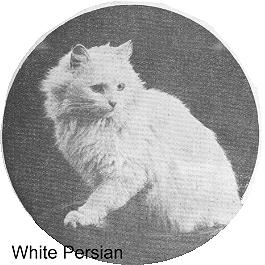

WHITE PERSIANS From a 1914 news article

A LOVELY CAT (Hampshire Independent, 1st August 1914) by Ernest Roberts. I have been asked to say something about the white Persian cat. All must admit that when seen in the condition in which we expect to find it at a good cat show this is a lovely animal. Unfortunately, it is not easy to keep it in this attractive condition, especially in towns; and this, no doubt, accounts for its comparative scarcity, though considerable number of the variety have been imported, and much better specimens are exhibited than was formerly the case.

It is an extraordinary fact that kittens of this variety are commonly born with eyes of odd colours, one being blue and the other either yellow or less commonly green. In the East odd-eyed cats are valued; but this is not the case with us. The colour that is desired is blue, of a deep sapphire tint. Eyes that are both yellow not infrequently occur, but these now stand no chance at shows. Kittens that are going to have blue eyes throughout life can be distinguished by the brightness of the blue colour when the eyes first open, a shade of grey indicating the likelihood of a change of colour. The colour of the eyes is not directly inherited as one would expect, and kittens by odd-eyed parents, of which only one has blues eyes, may be expected all to have blue eyes. It would, however, be risky to use a yellow-eyed parent for breeding unless in all other points it were so exceptionally good as to make it particularly worth breeding from.

A cat of this variety may be a beautiful specimen, but it must be in perfect condition to win at a show. Washing long-haired cats is risky, especially in the autumn and winter, when most cat shows are held, besides coarsening the coat somewhat. The usual method of cleaning it is by means of a shampoo powder, which, though quite harmless, brings the fur into a clean and beautiful condition when thoroughly rubbed in and brushed out. After taking this trouble, it is advisable to make sure that the pen in which the cat is to be exhibited is perfectly clean. It is, unfortunately, quite true that white cats with blue eyes are more often than not stone-deaf; and the reason for this is believed to be somehow connected with the absence of pigment in the inner ears.

BLUE PERSIANS - DIVERSE NEWS REPORTS 1912 - 1914

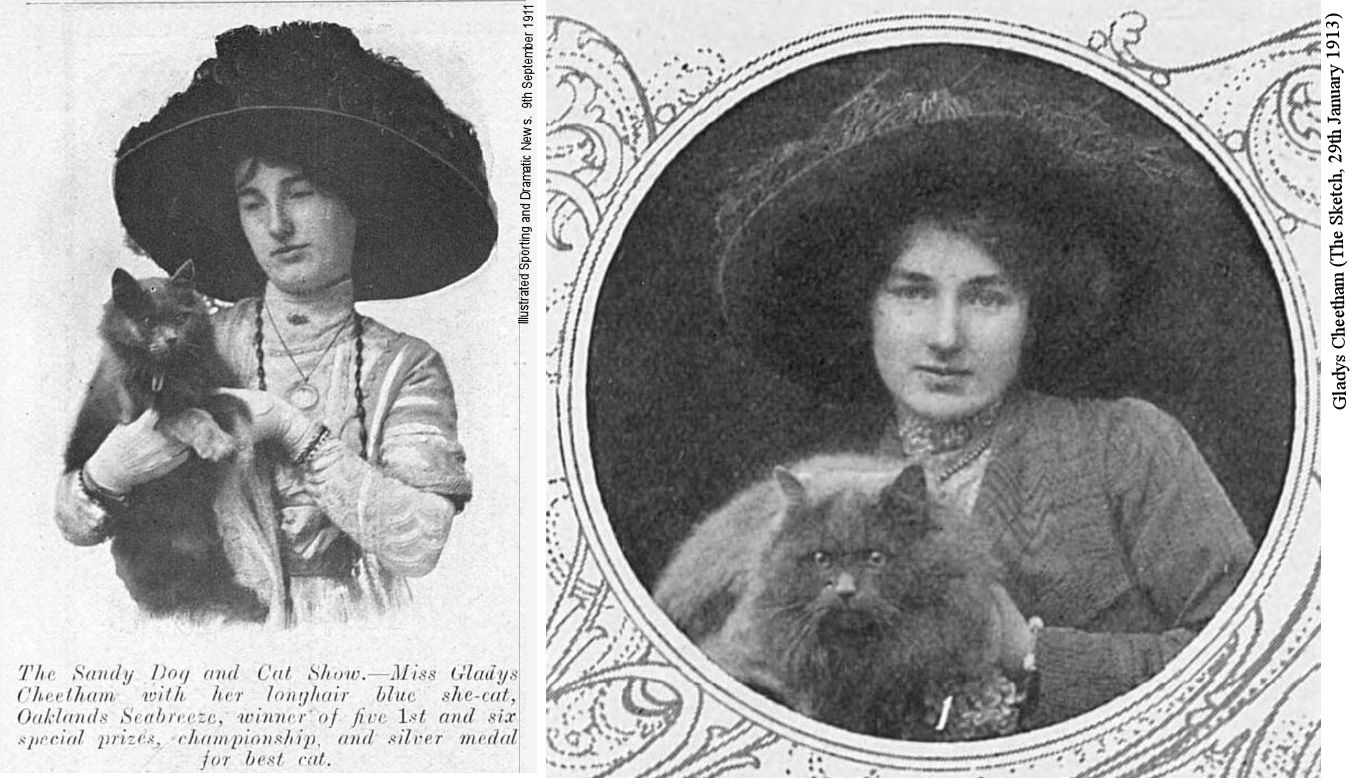

One of the most successful breeders of blue Persians was Miss Gladys Cheetham whose show successes were reported not only in “Fur & Feather” but in the national and global press. Comments about her cats gives a good idea of how far the Persian had progressed from its Angora roots to a round-headed, round-eyed, cobby-bodied cat.

What is called a King-Championship was awarded at the animal show of the Southern Counties Cat Club at the Royal Horticultural Hall, London, on January 11 [1912]. The winning cat, which happened this year to be a "queen," is reckoned the finest cat in Great Britain. The long-haired blue, Oaklands Sceptre, belongs to Miss Gladys Cheetham, of Oaklands, Brighouse, Yorkshire, was awarded this championship. The cat won its blue ribbon for evenness of color, length of coat, large round "cobby" head, neat ears, and orange colored eyes. The most formidable rival of the opposite sex which Miss Cheetham's cat met was Mrs Fisher-White's Champion Remus, of Highgate, a handsome blue, which won the male championship. (Bruce Herald, 11 March 1912, Boston Evening Transcript, Jan 27, 1912).

Southern Counties Cat Club annual show, Royal Horticultural Society Hall at Westminster, January 1913: Quality throughout, however, was exceptionally good, as most of the best Cats of the day were on view. The judging for best Cat in show during the afternoon of the first day was followed with great interest, the award eventually going to Miss Cheetham's grand blue male, Oaklands Steadfast, which held a similar position at Birmingham. […] Mr. Mason's Classes: Longhair: Team [a class for multiple well-matched cats]: 1.Miss Cheetham, the winning Blues, Steadfast, Seabreeze and Sheila, three of the very best blues seen this year, in rare order. Miss Simpson's Classes: Longhairs: Blue Male, [number of entrants] 14: 1,ch, ch.cup, and specials, best Cat in Show, Miss Cheetham, Oaklands Steadfast, beautiful eyes, A1 shape, rare head and bone, good coat, level colour, and in fine trim; 2, Mrs. G.Wilson, Sir Archie of Arrandale, massive cat, strong in bone, with great wealth of coat, not as cobbily built as leader, and loses in eye and soundness of colour underneath, in perfect condition; 3, Miss Cheetham, Oaklands Silvio, nice head and bone, big frame, loses eye and coat, the latter being inclined to lay flat; r. Mrs. Finch, Sir Reginald Samson, paler in eye and not as sound in colour, good coat, grand size and bone. Longhairs: Blue Female, [number of entrants] 19: 1, Ch, specials, 2 &3, Miss Cheetham, we doubt if a trio of better blue queens was ever penned at the same time, by one exhibitor; they were Oaklands Sheila, Sceptre, and Seabreeze, three wonderful Cats, and penned in magnificent coat and condition; I rather liked Sceptre as leader, though on the day, the leader carried a bit more bloom, whilst those wide-awake eyes are very fascinating. Nevertheless, they are three truly wonderful Cats, and need no further description." (Southern Counties Cat Club annual show report, Fur & Feather, 24th Jan 1913)

The well bred cat supplies an instance of how far culture can eliminate natural instincts. Just as the man of culture, whose physical courage is sapped by much study in the acquirement of knowledge, refuses to "soil his hands” by assaulting a boorish person who insults him, so the well bred cat who has won prizes for prettiness at cat shows refuses to soil his or her claws by catching a mouse. Miss G. Cheetham, whose blue Persian cat named Oaklands Steadfast was pronounced by the judges to be the best cat at the show held in London by the Southern Counties Cat Club, states that many high bred cats in her possession will not so much as look at a mouse. (The Age, March 1st, 1913)

London Mail: Miss G. Cheetham, whose blue Persian Oaklands Steadfast was pronounced the best cat in the show, with four firsts and three special awards, said: “I breed exhibition cats simply for the pleasure of producing the most perfect cat, not for any ulterior purpose such as one has in breeding greyhounds or bloodhounds or spaniels. Highly bred cats are no more intelligent or clever than ordinary back garden cats, and certainly many of mine will not so much as look at a mouse.” The Duluth Herald, 15th February 1913

After her show successes in 1912, 1913 and 1914 , Miss Cheetham got plenty of coverage in the “catty press” and also in ladies’ magazines of the time. In the 28th February 1914 issue of “The Queen - The Ladies Newspaper” a contributor (suspected to be Frances Simpson!) described in detail a visit to “'Miss Cheetham's Cattery at Oaklands, Brighouse” and many of the cats residing there: “I was invited to accompany Miss Gladys Cheetham on her morning feeding round. She carried a large deep can of steaming cooked meat, and with wooden spoon distributed it in clean earthenware dishes placed ready in each cattery. We came first to the large enclosure where Steadfast, the superb stud cat, lives, disporting himself. He was told 'to roll for the missus,' whereupon the big fluffy fellow threw himself down and turned over and over. Then having earned his meal he quickly set to work on the well-filled dish of meat. This grand male has been Miss Cheetham's property for a little over a year, and has won five championships. His eyes are so deep in colour as to be startling […] Sheila is another grand blue queen, and in eye and shape is hard to beat. She had a litter, now eight months old, by Steadfast, and two of these, Sybil and Sue, were two lovely snub-faced kittens, with glorious eyes. Miss Cheetham is very proud of this promising pair. Sheila, the mother, has once been the Best in the Show. Her grown-up daughter, Stella, by Big Ben, is a taking little cat, full of quality, but on the small size. She had a touch of show fever on one occasion, when her owner had a run of bad luck and lost several valuable kittens. Stella's hardy constitution pulled her through, but the illness stunted her growth. She has had one kitten, and Simole is a fine specimen who, with Sybil and Sue, make a dash for their plate of food, and then tried to take pot luck from the deep tin of meat by dipping their paws down and fetching up tit-bits.”VARIOUS BREEDS IN BRIEF(1927)

In 1927, judge Mrs Basnett reported on the Paris Cat Show held on 14th and 15th of January by the Cat Club de France and wrote, " Looking through my catalogue I saw a class marked 'Chats de Chartreux,' which did not appear to be a breed known in England, so I went round to find out what they were and was told 'The American cat' - and concluded that nobody was quite sure as another owner said they were Maltese."

Mrs Basnett also wrote "The Sacred Burmese Temple Cats interested me very much, with their long fur on the tail and coat resembling that of a poorly bred Persian; their colouring is exactly like that of the Siamese, but their feet sometimes have white toes. I was given to understand that they are very difficult to rear, only about one in ten survive. I do not think they possess the same quick movements as the Siamese, life to them seems much more dreamy and slow, but they are very loving and intelligent." This clearly referred to the Birman; confusingly the name Burmese Temple Cat was also used at that time for the gold-eyed brown Thai cats analogous to modern Burmese or brown Orientals.

In 1927, Mrs Amy Lawrence wrote "In the Natural History Museum [South Kensington, London] there is an enormous cat which is said to be a 'Russo-Persian' cat. It has an immense coat, and is similar in every way to a Persian long-hair, except that it is larger than any specimen I have ever seen. An old uncle of mine possessed what HE called a Russian cat, also a long-hair with immense coat and very large." However the only "Russian" cats Mrs Lawrence had seen at cat shows was the small short-haired Russian Blue that looked like a blue Siamese cat! Her uncle's huge Russian cat had been a tabby.She wondered "Do Blue Russians really come from Russia, and if so, then where do those immense long-hairs come from, and why were they called Russians even by Museum authorities?"

In 1926, Dr Jumaud's book "Les Races des Chats" (The Breeds of Cats), which was based largely on the works of Professor Cornevin of Lyons, described the Carthusian cat (felis catus carthusianorum) and Tobolsk cat. The Carthusian was apparently the "Maltese cat" known the the Americans, though Jumaud's description referred to a large head with large, full eyes, short nose and small, erect ears. Its coat, he said, was half long and woolly and the colour was grey with bluish reflections. However, there was another variety of Russian cat known as the Tobolsk variety: "This variety, described by Gmelin, exists in Siberia, and is sometimes called the Tobolsk cat. It is larger than our common cat, and somewhat resembles the Carthusian in shape. The head is large, with big eyes, short nose, and small erect ears. Coat: as is fitting for an animal of a cold country, the Tobolsk cat has long fur, longer than that of the Chartreuse cat. Its texture is woolly, and in colour, uniformly reddish."

Cat Gossip, 27th April 1927 (edited by H.C. Brooke): “COON CATS. The American papers constantly make reference to the “Coon Cats” of Maine, which many writers fatuously maintain to be derived from a cross with the Raccoon. The animals is so distinct from the felines that such a cross is doubtless impossible, and even if it did occur, the resultant progeny would be true hybrids and sterile. We did, however, imagine it possible that there might be a very strongly marked local race as distinct form ordinary cats, as, for instance, the Abyssinian from the British cat. We, therefore, consulted our colleague, Mrs. Taylor, of “The Cat Courier,” who kindly replies:- “About the Coon Cat: we do not believe in any such animals. Some people incorrectly call our Maine L.H. Cats Coon Cats, but they are really nothing more or less than the Persians running loose and badly mixed as to colours, some sort of mixed up brown tabby or A.O.C. Colour.” This is what we expected. It is singular that some people, directly they see anything a little unusual, must at once try to explain it by referring it to some weird and wonderful cross. Many years ago Manx kittens were seriously exhibited and notified in the Press as hybrids between Cat and Rabbit!"

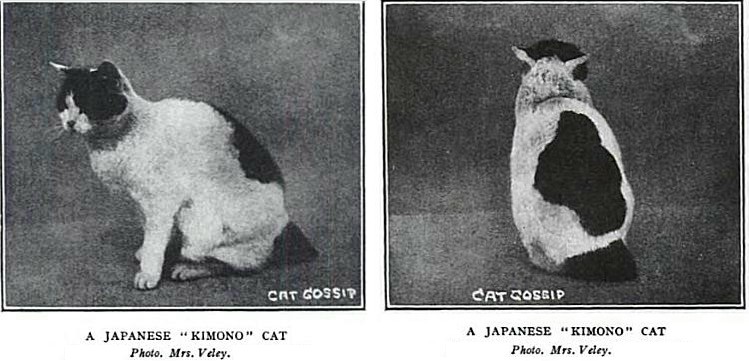

Dr. Lilian Veley, described the Sacred Japanese Cat in a September 1927 issue of “ Cat Gossip” (edited by Mr HC Brooke): “As far as I know, no other ‘sacred’ cat than this one, which I photographed in 1910, has ever been brought out of Japan. I am told that every cat in Japan which is born with a certain marking is considered as sacred - at least by some sects or some portion of the public - it is held to contain the soul of an ancestor, and is sent to a temple. No such cat would ever be parted with; this one, I was informed, was stolen by a Chinese servant, and carried on board a ship. Here it became the property of an English officer, who would have wished to return it to its temple, but dared not do so on account of the feeling aroused by the theft. It was brought home, and eventually came into the possession of an English family in Putney, who respected its traditions, and with whom it enjoyed a happy home and lived to an honoured old age. It died about 1911, soon after I had photographed it. The cat was black and white in colour, the black patch on the back being the ‘sacred’ mark - which is supposed to resemble a woman in a kimono. Its tail was short, black, very broad, and almost triangular in shape. It was almost uncannily human in its ways, and lived entirely on raw meat, refusing all other foods. I was grateful for the opportunity afforded me of photographing it, and never even showed the photos to anyone, though I gave a copy to its owners, who wrote and informed me when its death took place. I understand that the cat, which was a female, refused all mates, and never had any kittens.”

To which HC Brooke responded “An analogous instance of certain markings, occurring in an ordinary species, being held, at least by some sects, to confer sanctity - though very probably in the first place due purely to priestcraft - may be found in that of the sacred bull Apis, in ancient Egypt. Here also black and white were the colours; but white on a black ground... . At Memphis he was worshipped as being the reincarnated god Phtha; he was kept in great pomp by the priests in the Temple, and the whole land mourned his death.”

THE DOMESTIC SHORT-HAIRED CAT (1936)

"He is only an alley cat, but we love him." One often hears people say this, or something like it, but it is a mistaken sense of values that leads anyone to speak apologetically of the household pet because it has short hair and no pedigree. For the domestic short-haired cat is a member of as good a breed and is as capable of development as is the Persian, the Manx, or the Siamese. But the Persians, the Manx, and the Siamese have the glamour of imported stock, whereas domestic short-haired cats have always been with us.

It is a proof of the amazing strength of the strain that among its strays and hoboes, cats without benefit of breeding, living as they can in holes and corners, one finds kittens that are really beautiful in colour and in build. One does not see many domestic short-hairs in shows, but ask any of the few exhibitors of such animals where their stock came from, and the answer usually is, "Oh, just a couple of cats that I picked up." A short-haired silver tabby that began life as a stray was second best cat in the largest show in New York City in 1934- It is interesting, too, to note the pure whites and blacks and Maltese among these so-called alley cats. Breeders take great pains to preserve purity of colour in Persians, yet nature does it for the shorthairs without any fuss at all.

What was the origin of the cat? Darwin declared that he had never been able to determine with certainty whether these animals were descended from several distinct species or had only been modified by occasional crosses. As far back as we know there were many varieties; chief among them the Asiatic cats, including the Persians, the Angoras, and the Siamese, and the European cat, now known as the domestic short-haired cat. As to the beginnings of the latter there is one theory that I like to believe, and it is as reasonable as the next one. When I see a neglected alley cat I like to think, "Long before the Christian era your forefathers were worshiped as gods." Not that this is any comfort to a hungry cat, but it seems to invest the poor thing with a sort of dignity to reflect that it derives from the sacred cats of Egypt.

Richard Lydekker is one authority who holds this view. In the Library of Natural History which he edited and part of which he wrote he says, after mentioning that the ancient Egyptians tamed and trained the wild caffre cat, "We are inclined to follow those who consider the caffre cat the original parent stock of the domesticated cats of Europe." These cats are supposed to have entered Europe by way of Gibraltar. Probably most of them were undomesticated wanderers, but it is a fair guess that some of the sacred cats, bored perhaps by attending goddesses, joined the emigrants. Many reached England and settled there, and, cats being great sailors, their invasion of America was only a question of time. It is thought they may have been modified by mating with native wild cats in the north of England, but not much, for the caffre cat in Asia and Africa is about the size of one of our domestic cats and looks not unlike them.

At any rate there is the theory, and here are our cats. Despite the indifference of breeders, the standard for domestic short-haired cats is pretty well fixed in England and the United States, and the show rules of cat fanciers' associations include classifications for them. I do not know that shows are good things for our house pets. If you love your cat you don't need a judge to tell you its qualities, and a cat who has always been a homebody is likely to find the crowds and excitement and strain of an exhibition rather terrifying. However, blue ribbons do lend prestige, and a wider participation in shows would at least give our humble alley cats a better social position.

Domestic short-hairs must conform in colour of coat and eye colour to the standards laid down for long-hairs. These you will find in the chapter on Shows, and Long-hair Standards. One must not expect to see in domestic cats the delicate shades that breeding has produced in the Persians, but there are handsome silver tabbies, brown tabbies, orange tabbies, and tortoise-shells, as well as blacks, whites, and blues. I have heard tortoiseshell cats, with their Joseph's coats of black, orange, and cream, called calico cats in American rural districts. Our short-haired blues are generally known as Maltese. Eye colour is largely a result of selection, and shorthairs are seldom perfect in this respect, but I once picked up a stray Maltese kitten who had the brilliant copper eyes of a Persian blue. Attached to the Washington Square Book Shop in New York City is a beautiful yellow short-hair with eyes of a warm yellow, matching his coat. I don't know how he would be listed in a show, but if good looks and good manners merit a prize he could compete with any thoroughbred, unpedigreed though he is.

In their build the short-haired cats differ signally from the Persians. They are more slender, more lithe, and more vigorous-more like the feline creatures of the wild. Their noses are longer, their heads less round, their ears more upstanding. The standard requires a well-knit and powerful body, a deep chest, and a tail rather thick at the base, tapering toward the tip, and carried level with the body. The coat must be heavy but not cottony, and any sign of a long-hair bar sinister is fatal to success in the short-haired classes. Cats with lockets of a contrasting colour under the chin are denied winners' ribbons.

Our domestic cats are the Cinderellas of their race, sitting in chimney corners and doing the mouse-catching of the house while the Persians go about getting themselves in the cats' social register. But they are also adventurous. It is mostly the common cats who go down to the sea in ships and who patrol the farms and stores of the world for rats. They are very practical pets. You may not be able to purchase a pedigreed cat, but you can always find a short-haired kitten that needs a home. They have an intelligence which has been sharpened through many generations by the necessity of scrambling for a living, but hardships have not marred their native courtesy. Meet a cat on the street and it hardly ever fails to rise, to bow, and to utter a polite "P-r-r-t!" of greeting-except, of course, the poor strays whose experiences have made them distrust humanity.

The life that has stimulated their wits has also given them a heritage of terror and uncertainty. It is rather pathetic to see how this uncertainty will show in adopted strays in an abnormal anxiety about dinner. Whereas the Persians whose lives have always been safe are like Hafiz, the cat in George Eliot's Daniel Deronda, who sat calmly watching the family at the tea table, "regarding the whole scene as an apparatus for supplying his allowance of milk."

ABOUT PERSIANS AND ANGORAS (1936)

In the beginning there were Persian cats, brought to Europe and America from Smyrna and other ports on the Oriental coast, and Angora cats, from the mountainous Turkish province of Angora. The Persians had silky, uniformly long and abundant coats, and broad heads; the Angoras had narrow heads, and their hair was longest on the stomach, pendent like that of the goats of their native country. Interbreeding has made the two one, and the official term is now "long-haired cat." Round heads, wide-set eyes, firm legs, cobby bodies, and long, fine, even hair have been the objectives of most breeders, and it is the Persian characteristics that are strongest in the best long-hairs today. The narrow Angora head is considered a blemish and is seen only in the poorer specimens of the breed.

The captains and crews of trading vessels that plied between the Orient and our Atlantic ports brought the first long-haired cats to this country. They throve best in Maine, probably because of the cold climate, and today in Boothbay Harbor and other Maine coast towns long-hairs are as common as short-hairs are in most parts of the United States. They are known as Maine coon cats, and there is a legend that the Adam and Eve of the tribe were brought here by a certain Captain Coon and got the name from him; but I have not been able to run Captain Coon's record to earth. The generally accepted theory is that some old Maine farmer who saw an animal with a broad head and a bushy tail in his poultry yard and at first supposed it to be a raccoon but found it was a cat, first gave the name.

But these coon cats were never show stock. The marvellous, proud, long-haired beauties who take awards in American shows were mostly imported (they or their progenitors) from England by breeders. In the Mauve Decade and the early part of this century the cat vogue flourished in England and Scotland; and the Champion family, Miss Elsie G. Hydon, Miss Evelyn Langston, and other scientific breeders produced some fine Persian blues, chinchillas, silvers, tabbies, and other varieties of the long-haired cat. Some of these breeders emigrated to the United States with their cats; Americans took up breeding, sales increased, cat societies sprang up, shows multiplied . . . . and then came the World War, and put an end to this, as to so many pleasant things.

It is only in recent years that the interest in cats in England and America has begun to revive, and there is little pecuniary gain in breeding them now. People have not the money they once had to pay for pedigreed animals, and it costs money, in stock, in overhead, in care, and in food, to raise thoroughbred cats. It is fortunate that there are breeders who are true cat-lovers and are content to work for small profits because they do love their cats and take delight in developing the best. And there never were Persians like those of today. Even Miss Carroll Macy's King Winter, the grand chinchilla who was the sensation of cat shows twenty-odd years ago (I can still see him sitting royally in his silk-lined cage with his hundreds of trophies from former shows for a background)-even he would probably go down, in a battle of points, before some of the champions exhibited now.

The story of experiments in pigmentation, of controlled matings by which the many colours and shades of colours of long-haired cats have been developed, is too long to be told here. Of all the colours the blues are by far the most popular. I do not know how they started, but Mr. C. A. House, a veteran English judge of cats, suggests in his book, "Our Cats and All About Them", that they derive from Russian blues, cats with thick short fur, like plush, that were first brought to England from Archangel by sailors. Harrison Weir, the artist, who wrote the first cat book (I believe) and got up the first cat show (it was in the Crystal Palace in London more than half a century ago) declared that the blues were just a variant of the blacks. The earlier blues had a dark streak along the spine, but the fanciers worked hard to eliminate this and produced the true, even, lavender blue which is the ideal today.

I love the blues, I suppose because mine were blues; they had the same grandfather that Miss Hydon's first American cats had - Siegfried, a magnificent male raised by Miss Shirley Turner and Miss Elsie Bunker on the Bunker farm in Merrick, Long Island, where my cats now lie in a wood beside the pond where Siegfried took occasional swims in hot weather. Siegfried went to California, and is buried there, but his descendants are many in the land. He was a brave cat, but very fatherly, not at all above tending baby kittens when their mother went gallivanting. But Siegfried's title to excellence was not so much in his coat, though that was very fine, as in his build and expression. Fine coats do not always make fine cats, and a Persian with beautiful hair may be inferior in bone formation. In choosing a Persian kitten one should remember that the important points are the massive build and the sweet expression which properly set eyes give to a good long-hair.

Many people think that Persians are lofty and indifferent, and they do often seem that way in shows, but who would not? We would be bored and haughty if we were set up in cages with an endless procession of cats walking by us, making personal remarks about us, carrying us to and fro to judge our points. It is an evidence of the amiability of cats that they so seldom go berserk in shows. There is an impression, too, that Persians are delicate and rather lazy, that they are not good mousers, that they are like the lilies of the field that toil not. But I have found that Persians have hearts that are just as stout, under their fluffy attire, as that of any short-haired alley cat. It may be that their digestion requires special care, but my long-hairs were no more susceptible to disease than my short-hairs. Of course a Persian hobo does look a wretched creature, just as a two-legged down-and-outer whose clothes came originally from Bond Street or Fifth Avenue looks more forlorn than one in overalls or a Mother Hubbard.

The few Persian strays I have known showed good stuff. Take Black Pussy. On a sleety day two winters ago Robert Claiborne, a New Yorker who likes cats, picked up a draggled, emaciated one on Third Avenue and took him home. He was indeed almost at the last gasp, but he was not whining; he faced adversity with head unbowed. Washed and brushed, fed and petted, he bloomed out into a handsome, urbane Persian, sinking gratefully into the lap of luxury. I suppose he was returning to his original cycle. Then came another cycle. Mr. Claiborne sailed for the Virgin Islands and took Black Pussy along. Armed with a clean bill of health from the Speyer Hospital, the cat passed quarantine and took up his duties with his master's firm, the Virgin Islands Fruit Products Company in St. Thomas.

There were huge rats in the warehouse. Black Pussy cleared them out, and a sight it was to see him, with his tail like a plume, bringing down a rat almost as large as himself. Then he sought other game. No lizard or crab was too much for him, and once he killed a ten-inch centipede and brought it home. His cache was the top step of an old stone stairway, and there was quite a fuss when one of the negroes stepped barefooted on the centipede. But no negro dared molest Black Pussy, and in his favourite post, mounted on a sea wall near the warehouse entrance watching for crabs, he is a most effective watchcat.

He still hunts, and he has taken up sailing, though he does not try to handle the boat; he prefers to sit in the prow like a figurehead. He is fully aware of his decorative value. He lies for hours in the green caverns of the brushing coconut palms on a terraced roof, as if he knew he could not find a better background for his ebony self. I had an S O S from Black Pussy's master recently. The cat was indisposed, owing to eating lizards, which are not good for cats. I immediately mailed medicine, and though at first he retreated up a spreading grapevine to avoid it, he capitulated, came down, took his pill, and recovered.

Black Pussy is quite a conversationalist. He has a whole lexicon of miews, one for every occasion. His behaviour and his life are a complete proof that a Persian can be just as intelligent and as capable as any short-haired cat that ever lived.

In 1936, long-hairs attracted far more attention than shorthairs. The next chapter continued with "Shows and Long-hair Standards"

In the autumn there begins a mighty grooming and conditioning of cats that have show possibilities, whether these be in fact or in the fancy of fond owners. For in November the cat-show season opens. Among the first shows in New York City are those held by the Cat Fanciers' Association, Inc., and the United Cat Clubs of America, Inc. Each of these organizations has many member clubs in the United States and Canada. There are other large societies, such as the Cat Fanciers' Federation and the American Cat Association, and all of these, and their member clubs, have shows through the autumn and winter. There are cat shows from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Maine to Florida, and naturally (for cat people are very human) each show is the biggest and best of its kind. Among the specialty clubs (those devoted to one breed) the Persian clubs far outnumber all others, and in exhibitions, except for those that are solely for other breeds, the long-hairs always predominate.

Shows are necessary to the cat fancy, as breeders in the aggregate are called, but I would not exhibit a pet cat. Old troupers may thrive on it, as movie stars do on the acclaim of the public; I knew one champion who when his travelling cage was put on the floor along with his trunk of trophies would step into it and settle down, ready for a journey to the far side of the continent perhaps. But a show is an ordeal for most home cats, and there is always the danger of infection where numbers of cats are gathered together. No matter how many precautions the show managers take, this peril does exist. If, however, you wish to exhibit your cats, a necessary preliminary is to register them with some recognized cat club, procure the club's show rules, and study the classifications and standards. Select the club that is sponsoring the show you mean to enter, for rules differ. If your cats have been well cared for, special conditioning is not necessary. A cat that is properly groomed and fed and kept happy is ready for a show any time, except in the hot months, when no cat's coat is at its best.

To condition a neglected cat, valet it every day according to the directions in the chapters On Grooming a Cat, Diseases of the Ears, and Diseases of the Eyes. No judge would admit a cat with a hint of cots in the hair or canker in the ears. To clean white cats there is a white fuller's earth, but well baked flour will answer. Of course it must be thoroughly brushed out of the hair. Plenty of nourishing food, and a half teaspoonful daily of cod-liver oil if it seems needed, will put your pet into the right physical condition.

Cats should not be fed before a journey, even a short one by automobile. At shows there is a feeding committee, and chopped beef is taken to the cages at regular times, but you may take your own food if you prefer. It is wise to stay by your pet during the show, in order to give it confidence and guard it against any possible harm at the hands of some ill-advised visitor.

There are special carriers and crates to be had if one is sending a cat to a distant show, but if you ship a cat by railway you risk a tragedy. Once a cat and two kittens were sent from California to New York, and when the crate was opened the kittens were dead and the mother so near death that she had to be killed. Somehow the trainmen had overlooked the instructions about food and water. Even on short journeys accidents may happen. I knew of a Persian kitten whose cage was crushed, with the kitten inside, by the fall of express packages insecurely piled above.

But if shows have their risks they undoubtedly have their delights and their advantages. It is gratifying if your pet makes a win, and even if it fails you learn something from what the judges say. But show managers are canny. There is generally something, if no more than a ribbon, for every cat. And you can avoid a too crushing defeat by conning the standards closely and not entering your pet in a class where it obviously has no chance of success.

The long-hair standard demands a body that is low on the legs, deep in the chest, and massive across the shoulders and rump, with a short, well rounded middle piece. The head must be massive too, with a broad skull, and it must be well set on a neck that is not too long. The ears must be neat, round-tipped, and set well apart; the cheeks full and the jaws powerful; and the nose of the snub variety, and broad. The eyes must be large, full, round, very brilliant, and wide set, with that serene gaze which distinguishes the Persian cat. The back must be level, the legs thick and strong (the forelegs perfectly straight), and the paws large and compact. The rather short tail is slightly lower than the back, and must not trail when the cat walks. The hair must be long and fine over the entire body, and full of life, standing out fluffily; and the ruff should be immense. The brush must be full, and the ear tufts and toe tufts long and feathery. A "button" or a "locket" under the chin disqualifies a cat.

In-the Persian gamut the colours and combinations of colours are fourteen. The great point in a solid colour is that it shall be pure and even from the roots to the tip of the fur. Each has its right eye colour. White cats must not have any coloured hairs; the eyes are deep blue or deep orange. The blacks must be of a dense, coal black, with copper or orange eyes. The blues must be a real blue, and their eyes copper or orange. Red cats must be of a rich yet brilliant red, and the eyes copper or orange. A good chinchilla is of a pale, unshaded silver, with green eyes. Cream cats must be pure cream, free from markings; the eyes are copper or orange. The shaded silver cats are rather dark on the spine, shading gradually down the sides and face and tail to a very pale silver; the eyes are green. Smoke cats are black, shading to smoke ( a light undercoat and black points) with a silver frill and ear tufts; the eyes are copper or orange.

The body of a masked silver is chinchilla or shaded silver, with a black or dark silver face, and green eyes. Silver tabbies are a pale silver with broad black markings, and green eyes. The coat of the brown tabby has a tawny background, with broad black markings; the bars on the legs and tail are like rings, and on the chest they have the effect of necklaces. Copper eyes are best, but orange eyes are permitted. The red tabby has a coat with an even groundwork and markings of a deeper, richer red, patterned like those of the brown tabby; the eyes are copper, or a very deep orange. Tortoise-shell cats sport three colours, black, orange, and cream, and the colours are not brindled but in clearly defined patches. They have amusing noses, half black and half orange. The eyes are copper or orange. Last of all there are the blue creams, who have these two colours in patches, and copper or orange eyes.

Both Manx cats and domestic short-haired cats have the same standards of colour and eye colour as have the long hairs. Only the Siamese have their own special coats. The standards of build and body required for the three different short-hairs are described in the chapters on these breeds.

THE ROYAL SIAMESE (1936)

A cat may look at a king, but not many cats have the opportunity. Siamese cats for more than two hundred years have dwelt in the royal palaces at Bangkok and had kings, queens, princes, and princesses to look at. Those who did not live at court lived in temples and had priests to serve them. So they are not only royal but sacred, the modern prototype of the sacred cat of Egypt. Of course there have always been street cats in Siam, but they have kinks in their tails and do not count. The first Siamese cats to leave that country were two fine specimens that were given to some titled Englishwomen by the uncle of Prajadhipok, the recently abdicated king. They were much admired in England, and founded the line which soon became popular there, and, later, in America. The origin of the Siamese cats is obscure. They may have come from crosses between the sacred cats of Burma and the Annamite cats when the Siamese and the Annamese conquered the Burmese empire of the Khmers about three centuries ago.

The Burmese sacred cats were an ancient race of which little is known. It is said that they were like the Siamese in colour, but had splendid bushy tails and long hair [note: possibly the Birman, not the Burmese]. The Burmese, like the people of Siam, believed that the spirits of the dead dwelt within the sacred cats. I have seen in shows cats that were called Burmese, but I doubt if they were authentic. However, our best Siamese are genuine. King Prajadhipok must have had cats in his entourage when he last visited America, for he gave two to a New York woman during his stay. Siamese cats are like Prajadhipok. Though born to palaces they are very democratic and alertly interested in everything they see. A Siamese cat is more energetic and can be in more places at once than any other member of the Felis domesticus. I took my collie-setter Luddy to call on Frederick B. Eddy's Siamese in Red Bank, New Jersey, and he retired under a sofa with his tail to the world, disconcerted by a liveliness with which no mere dog could cope.

The number of Siamese cats in the United States is not large compared with the number of longhairs, but they are getting a good hold, and there is a flourishing Siamese Cat Society of America, which conducts its shows under the Cat Fanciers' Association of America. Its standard of points conforms to that of the Siamese-cat societies in England. True Siamese are medium in size, with a wellmuscled body, not fat, and very lithe and graceful in action. The head is wedge-shaped, long and narrow, the ears broad at the base and small at the apex and very neat and well-defined. The legs are rather thin and not long; the hind legs are slightly longer than the forelegs. The feet are somewhat smaller than those of the domestic short-haired cat. The tail is thin and tapering and not very long.

A good many people think that Siamese cats have kinked tails. So learned a commentator as M. Oldfield Howey asserts in his fascinating book, The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic, that the kinked tail has been a Siamese characteristic for two hundred years. There is a Siamese legend which says that somebody once tied a knot in a cat's tail to remind it of something (perhaps to leave the throne room backward) and the knot stayed. Another form of the story is that a princess strung her rings on her cat's tail while she bathed, and tied a knot to keep them from falling off. But the royal Siamese have no kinks. Any kinky-tailed Siamese in America were brought here by sailors who picked them up in the streets over there. Richard Lydekker in his Library of Natural History, after describing the "breed of cats in Siam reserved for royalty," adds, "Siam, together with Burmah, also possesses a breed known as the Malay cat, in which the tail is but half the usual length, and is often, through deformity in its bones, curled up tightly into a knot."

The coat of the Siamese is soft and short and glossy. The body is coloured a clear, pale fawn, the face is deep chocolate brown shading to fawn between the ears, and the ears, tail, legs, and feet are brown. Siamese kittens are born snow white, but the distinctive markings soon appear, and at one year of age these cats attain their loveliest contrast between the fawn and brown. After this they slowly darken. There is a blue-point Siamese in which the body is pale blue and the face, legs, and tail dark blue. Blue points are rare, a sort of "sport," but the Cat Fanciers' Association includes a class for them in its show rules. The pigmentation of the blue point is what is called recessive, and those who are curious about scientific breeding might be interested to know that if a seal point were bred to a blue point the darker colouring of the former would probably prevail in the kittens. The eyes of the royal Siamese are blue, and the better the cat, the darker are the eyes. In shape they are almost round, but with a slight Oriental slant toward the nose.

Devotees of the Siamese insist that they are the smartest cats in the world. But every cat-lover knows that his or her cat, be it Siamese or Persian or Manx or plain alley, is the smartest cat in the world.

THE MANX CAT (1936)

One of the few distinct breeds in 1936 was the Manx. No cat writer of the time could resist recounting some of the myths about Manx cats, including the misconception that they resulted from mis-matings with rabbits. This excerpt was published in the USA.

The "Mystery of the ships and the magic of the sea" envelop the beginning of Manx cats, or rather the beginning of our knowledge of them. This does not extend very far into the past. By shipwreck they came to the Isle of Man, leaving their tails behind them, if they ever had any. The cats will not tell, but I do not think they mind their taillessness. The Manx cats I have known appeared well satisfied with themselves, and I could almost imagine them saying to tailed cats, "Why have a tail? You cannot catch mice with it, or fight with it, or wash your face with it. Its only function is to serve as a handle for naughty children to pull, or, if you are a mother, something for your kittens to play with just when you want to take a nap."

As to the value of a tail as an ornament, that of course rests in the eye of the beholder. It is a matter of taste. People who own and admire Manx cats think that a tail makes a cat look awkward, and that the animals of their chosen breed are much trimmer and more graceful than your finest tail-wavers, as Manx owners call cats with tails. But in a world where conformity is the thing, deviation from type requires explanation, and there have been many attempts to explain why the Manx has no caudal appendage. Most of them are just legends. There is an old rhyme which says that the cat was the last of all the animals to board the Ark, and so Noah, impatient to be off, slammed the door on its tail.

Said the cat, and he was Manx,

"Oh, Captain Noah, wait!

I'll catch the mice to give you thanks,

And pay for being late."

So the cat got in, but oh,

His tail was a bit too slow.

Another version holds Noah's dog responsible.

Noah, sailing o'er the seas,

Ran fast aground on Ararat.

His dog then made a spring and took

The tail from off a pretty cat.

Puss through the window quick did fly,

And bravely through the waters swam,

Nor ever stopp'd till high and dry

She landed on the Calf of Man.

Thus tailless Puss earn'd Mona's thanks,

And ever after was call'd Manx.

There are, however;' more factual accounts connecting Manx cats with shipwreck and the sea. An old Manx newspaper states that early in the nineteenth century an East County ship was wrecked on Jurby Point, and "a rumpy cat swam ashore." There is a tradition that there were tailless cats aboard the Spanish Armada, and that two of them, escaping to land from one of the vessels which was wrecked on Spanish Head, near Port Erin, began the propagation of the breed in the Isle of Man. Another story has it that the Adam and Eve of Manx cats were the survivors of a Baltic ship that went down off the coast of the Calf of Man.

But whether they came from the north or the south, the east or the west, they became identified with the quaint little island in the Irish Sea, a feature in its trade with tourists, and a part of its folklore. At the Jubilee Congress of the Folk Lore Society in London, in 1928, Miss Mona Douglas, in an address on animals in Manx lore, said that the Manx peasantry believed that the cats had a king of their own, a wily beast that pretended to be a demure house cat in the daytime, but at night travelled the lanes in awful state, wreaking vengeance on persons who were cruel to cats. They believed, too, that the fairies were friendly to cats, and that it was of no use to shut Puss in, or out of, the house at night, for the wee people would hasten to her assistance, and work their magic on doors and windows to gratify her will.

Naturally, with ships plying between the Isle of Man and England, tailless cats soon became common in Liverpool and other coast towns. They have never been taken up by fanciers as the Persians have, or the Siamese, and people who breed them seem to do it not so much for commercial reasons as for the love of them. There is a British Manx Cat Club, of which Miss Helen Hill Shaw is the secretary. Miss Shaw has bred tailless cats for forty years at her home in Surrey, and she has done more than almost anybody else to keep the strain pure. It has not been easy. "I never know what to expect in a litter," she wrote me. "Even when two pure Manx cats are mated, there will almost always be one or two kittens with stumps or even tails." This suggests a theory. May it not be that long ago some experimenter tried selective breeding with cats whose tails happened to be short, producing shorter and shorter tails until they were eliminated, and may not the tailed offspring of tailless cats be throwbacks to that time?

The absence of a tail is not the only distinguishing mark of a Manx. The standard of points set up by the British Manx Cat Club says that a very short back and very high hindquarters are essential, since "only with them do we get the true rabbity or hopping gait." The flanks must be deep, and the rump round, "as round as an orange." The coat is what is termed double, very soft and open like a rabbit's, with a soft thick undercoat of fur. The head should be large and round but not snubby like the Persian's, and the nose longer than a Persian's but not so long as that of the domestic short-haired cat. The cheeks are prominent, the ears broad at the base and tapering. As to colour, Manx cats are found in all colours known in the longhaired or the domestic short-haired breeds, but the colour is not so important as the formation. The taillessness must be absolute. Not even the merest bud of a tail is permitted, and many cats cherished by their owners as Manx would be disqualified in any show where the judges knew their business. In the pure Manx there is a slight hollow where the tail starts in other cats. A tuft of hair is not a bar sinister, but the hair must not conceal a stump, for a tail is no less a tail for being hidden.

Manx cats are very individual, very brave and active, and loyal and affectionate. Miss Shaw says that she once witnessed the reunion of a Manx cat and his mistress, from whom he had been parted for four years. "He recognized her at once, jumping on her knee and then on her shoulder and kissing her, and he made it very clear that if he could help it he would not be parted from her again." The cats in the Shaw home in Surrey live together in the greatest amity. They sleep cuddled up together, any number of them, of different generations, and never quarrel. "Home would not be home to us," their mistress says, "without the warm welcome of our little Manx family, headed by Champion Josephus, the latest of a long line of champions descended from the kittens I brought to England, forty years ago, from a girlhood visit to the Isle of Man."

The Manx history continued with "How the Manx Came to America"

Around the year 1820 a family named Hurley owned a large farm at the place now called Toms River, in New Jersey. The love of the sea was in their blood, and as the sons grew up they had their own sailing vessels, and adventured far and wide. And among the curiosities they brought back with them from their voyages were tailless cats from England, which, they said, came originally from the Isle of Man. That is the earliest account I have of Manx cats in America. On the large Hurley farm the breed grew and flourished exceedingly, and when a son or daughter married and moved to another part of the country a pair of Manx cats went along as part of the dowry. Farmer Hurley's descendants and the descendants of his tailless cats have come down through the years together, and today his great-great-granddaughter breeds cats of this strain at her home, jolly Hill Farm, near Philadelphia.

I fancy that some of the Hurley cats wandered away from the farm and set up a bold buccaneering tribe of their own, which still endures, for there are many tailless and bobtail cats around Barnegat, New Jersey, which is not far below Toms River, and wild creatures they are, living by their wits. When you cross the causeway from the mainland to Ship Bottom, the first town on Long Beach Island, and turn north toward Barnegat Light, you may, if you have quick eyes, see them in the dunes. They subsist on the offal of the fishermen's catches, and perhaps they receive largess from the men at Loveladies' Coast Guard Station, but no man can come near them, and they will fight the fiercest dog.

Even in captivity they retain their outstanding he-cat qualities. The Hurley great-great-granddaughter, Miss Elsie Walgrove, says that her Manx are "great hunters, not afraid to go far and wide from home, and very sturdy, some of the neuters weighing as much as thirty pounds." One of her champions, Minus, attacked and killed a large weasel that had been stealing valuable cockerels from her chickenhouse, and Minus is a lady, too. Like all the Hurley family they love boating, and they enjoy riding on the market wagon. They will not, as a rule, take up with tailed cats, but with their own kind they are most friendly, and as companions for human beings they are, their admirers say, better than any dog.

I have been told by cat connoisseurs that there are few really good Marx, true Manx, in America. The trouble is, I think, that in shows over here the standard is not insisted upon as it is in England. People exhibit bobtail cats as Manx, and too many judges will let them get by on their markings and colour, which are not important in this breed. After all, though, if one is an individual owner and a connoisseur rather in the qualities that make cats delightful and stimulating than in points of structure, what does it matter if one's Manx has an inch of tail where the hollow would be?

I know a Manx cat named Michael; of the first litter of kittens born to his mother, a petite Manx called Mrs. Lena Dodds, he was the only one marked with the bar sinister. His mistress gave the perfect kittens to friends and kept Michael because even at the earliest age he showed character. Michael is now a handsome coal-black giant, swaggering about on his tall hind legs and ruling the cats of the neighborhood with a high handor should one say paw? He is afraid of nothing, and can find his way anywhere. Carried away once in an automobile, unknown to his owners, to a distant railway station, he came home on his four legs through many miles of traffic, all by himself. Both he and Mrs. Lena Dodds should belong to the nearest Izaak Walton Club, for they are tireless fishermen. They stand for hours on a flat stone in the shallow stream that runs through the foot of the garden, they even stand in the water, watching and waiting for a catch. Woe be to the fish that tries to swim past them. They have caught quite large ones with a single sweep of a paw.

Michael looks like a large black hare, and when he sees a strange cat his nose twitches as a rabbit's does when it is excited. But as both he and Lena hunt rabbits, squirrels, and chipmunks, it is hardly likely that they have rabbit blood. Their favourite game is hoppity-hide-and-seek, which they play in the tall grass of a neighboring field, and their mistress says that when one of them, leaping high in the air, succeeds in landing on the other, she could fancy that she hears them laughing-so mischievous and gay are their movements. Lena and Michael have very sensitive nervous systems, and their ears are attuned to the slightest sound. They are quick to hear the approach of an automobile; if it is the family car they run to meet it, but they are never deceived by a strange motor.

Few Manx cats are imported to America for breeding or show purposes. Those brought here are usually the pets of English families coming to live in the United States. Shipwreck has had its part, too, in bringing them, just as shipwreck carried the tailless cat originally to the Isle of Man. A huge gray and white Manx I know, named Jack, was purchased at the tender age of ten days from a Barnegat fisherman, and the fisherman said that the kitten's ancestors were washed ashore from an English ship that went down off the coast in a storm. It would be interesting to know why Manx cats, for all their intelligence and charm, for all the romance of their history, are still caviar to the general. Perhaps some time the popular taste will turn to them as it has to the Persians and the Siamese, but at present the majority of Americans seem to prefer their cats with tails.

The Manx History continued with "The Myth of the Rabbit-cat"

I had often heard of rabbit-cats, but had never met one until, quite recently, I was introduced to Swamp Angel, formerly of the Great Swamp near Chatham, New Jersey, but at the time of our meeting living in a New York apartment, and not liking it very much. One is always seeing newspaper stories about rabbit-cats. They tell of a hybrid creature with a cat's head and eyes, short forelegs, long hind legs, a brief tail like a rabbit's, close, soft fur like a rabbit's, and a trick of hopping instead of walking. The mother is always a cat, but the assumption is that the father was a rabbit, and no matter how emphatically science declares that the Carnivora and the Herbivora do not interbreed the rabbit-cat theory persists.

"No scientist could convince me that there is no such animal," one woman writes me. "I know I could swear to one. Twenty-two years ago, at Winthrop Rifle Range on the Potomac River, I saw an animal that had the general appearance of a cat but many of the characteristics of the rabbit. Its front legs were so short that it ambled rather than walked, and it would sit up any old time on its queer little bunny tail. Its fur was shorter and softer than a cat's, its jaw was not shaped like a cat's, and it made a sound quite unlike a miew. No one; who saw it had any doubt that its mother had met a rabbit in the woods."

In the Culver Citizen of August 22, 1934, appeared an article by Samuel E. Perkins III, formerly president of the Indiana Audubon Society, and leader of many nature hikes. He describes three strange kittens, part of a litter of which the others were ordinary kittens, all of them born to a cat who liked to go adventuring in the fields behind the Morgan County farmhouse where she lived.

"One would guess that she had been wooed there by a gentleman cottontail rabbit," he says. "Three of the kittens had rabbit tails. I felt the tail bone of one, a tawny male, and it had three vertebrae, each one-fourth of an inch long. It curved upward, hidden in a ball of fur. The kitten's back was arched like a rabbit's, and he used his hind legs as a rabbit does, hopping toward his saucer of milk. I suggested a Manx father, but no one had ever seen or heard of a Manx cat anywhere thereabouts. And in the Manx cat there is no tail at all, and no ball of fur such as these kittens had."

A moving-picture man made films and snapshots of the kittens, and Mr. Perkins wrote to Dr. H. E. Anthony, curator of mammals at the American Museum of Natural History, telling of his find and of a queer kangaroo-like cat he had seen in Indianapolis. Dr. Anthony replied that a cat was a cat. He discounted the hybrid theory. "So far as we are aware no such animal could exist," he wrote. "It is possible that your specimens are of the peculiar types of cat which appear unexpectedly, and are well known to students of genetics, though puzzling to the layman."

Swamp Angel was found by Charles Perry Weimer, the artist, in the course of a hunting trip along the margins of the Great Swamp. No man has penetrated into the depths of the Great Swamp, and strange creatures are said to inhabit it, but Mr. Weimer saw nothing strange in a nest of kittens he stumbled over until he lifted one, a coal-black atom, and perceived that it had no tail. All the others had tails, so Mr. Weimer left them to the mother, presumably off foraging, and tucked the odd one in his pocket. Mrs. Weimer named it Swamp Angel, and brought it up by hand.

Swamp Angel had Chatham people puzzled. His long, limber hind legs and his trick of standing erect on them, his lack of a tail, and his soft, thick fur led many who saw him to recall that there are numbers of black jack rabbits in the Great Swamp. Newspapers printed stories and pictures of him, and he became quite a celebrity. His traits are as contradictory as his appearance. He has none of the cat's sense of direction. If he wandered from the door of Mr. Weimer's Chatham studio, where he spent the first year of his life, he could not find his way back but would sit under a bush waiting to be fetched. Yet he is very intelligent and responsive. He has no miew, but a musical purr. He has claws on his forefeet but none on his hind feet, so he cannot climb. He has a rounder head, a blunter nose, and a more amiable gaze than have most bobtail cats, but that is what I think he is-a nice bobtail. The only alleged hybrid I have seen, Swamp Angel leaves me on the side of the scientists.

Clyde E. Keeler, of Harvard University, explains these cat eccentricities on the ground of exostoses or bony distortions of the vertebral column. He writes me: "These distortions are commonly found in human beings suffering from arthritis. They characterize many Siamese cats, the Manx cats, and the bob-tail which is so often erroneously called rabbit-cat. In inbred stocks a particular grade of exostoses will become characteristic of the strain. The Manx cat is bred for complete loss of tail. The Siamese when affected has a kinky tail. These exostoses are found in bulldogs, and in several varieties of mice." Siamese-cat societies would excommunicate Dr. Keeler for mentioning Siamese and kink-tails in the same breath. They call kink-tails Malay cats. Kink-tailed cats abound in Malay Land, and they probably have corrupted Siam. People who have lived in the Philippines tell me that all the cats in those islands have kinks, as if somebody had tied knots in their tails when they were very young."

It is ignorantly said that mutilations far back in the strain account for the crooked tails and the taillessness of some cats. Certainly there have been mutilations. James Baillie Fraser, a traveller-writer of the last century, told of islands off the coast of New Guinea where all the cats had docked tails. Their owners did it to protect them from impecunious neighbours who liked cat stew. By burying the tail of one's cat with suitable incantations one could bring terrible illnesses on the thief who dared to cook and eat the cat. So docked cats were safe. However, we know that acquired characteristics are not transmitted.