|

MUTANT CHEETAHS |

Mutants are natural variations which occur due to spontaneous genetic changes or the expression of recessive (hidden) genes. Albinism (pure white), chinchilla (white with pale markings) and melanism (black) are the commonest mutations. Erythristic (red), leucistic (partial albinism/cream) and maltesing (blue) are also been reported. Sometimes the markings are aberrant e.g. too sparse or too heavy (abundism), giving the appearance of a pale or dark individual. Numerous colour and pattern mutations occur in domestic cats so why are they less common in big cats? Wild cats displaying these traits may be less likely to survive to pass on the traits. In captivity, humans control which traits are bred, hence the multitude of domestic cat colours and types. In the wild, nature selects against any trait which does not enhance the animal's survival chances.

In the past, the obvious reaction to any unusual big cat was to shoot it for the trophy room. As a result, many interesting mutations may have been wiped out before the genes were passed on. Some colour mutations which would disadvantage a wild big cat are bred in captivity and are not viable in the wild. It is questionable whether these mutants should be perpetuated for the sake of curiosity or aesthetics alone.

I am grateful to Paul McCarthy for researching and providing extensive material and references.

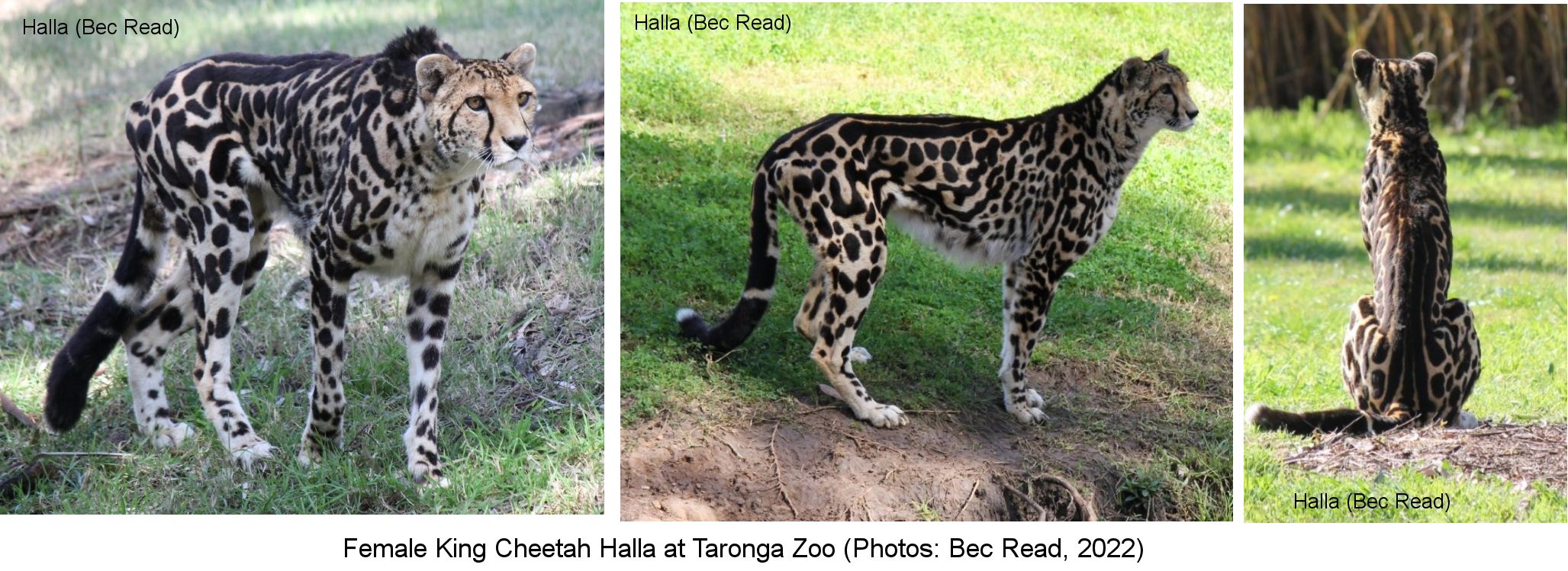

KING CHEETAHThe king cheetah is a mutant form of cheetah. This may be a form of abundism where spots coalesce into swirls. Alternatively, it may be that cheetahs can also be striped as well as spotted (like blotched tabby and spotted tabby cats). The blotched tabby was one of the first pattern mutations in the domestic cat so it would not be unusual to see this pattern mutation appearing in other cat species. It was originally believed to be a new species of cheetah or a cheetah/leopard hybrid, but is now believed to be a relatively recent mutation. The identity of the king cheetah was not resolved until researchers noticed that some cheetah litters contained both striped individuals and spotted individuals. The darker patten may give better camouflage in less open territory and it has been suggested that evolution is allowing cheetahs to exploit new habitats.

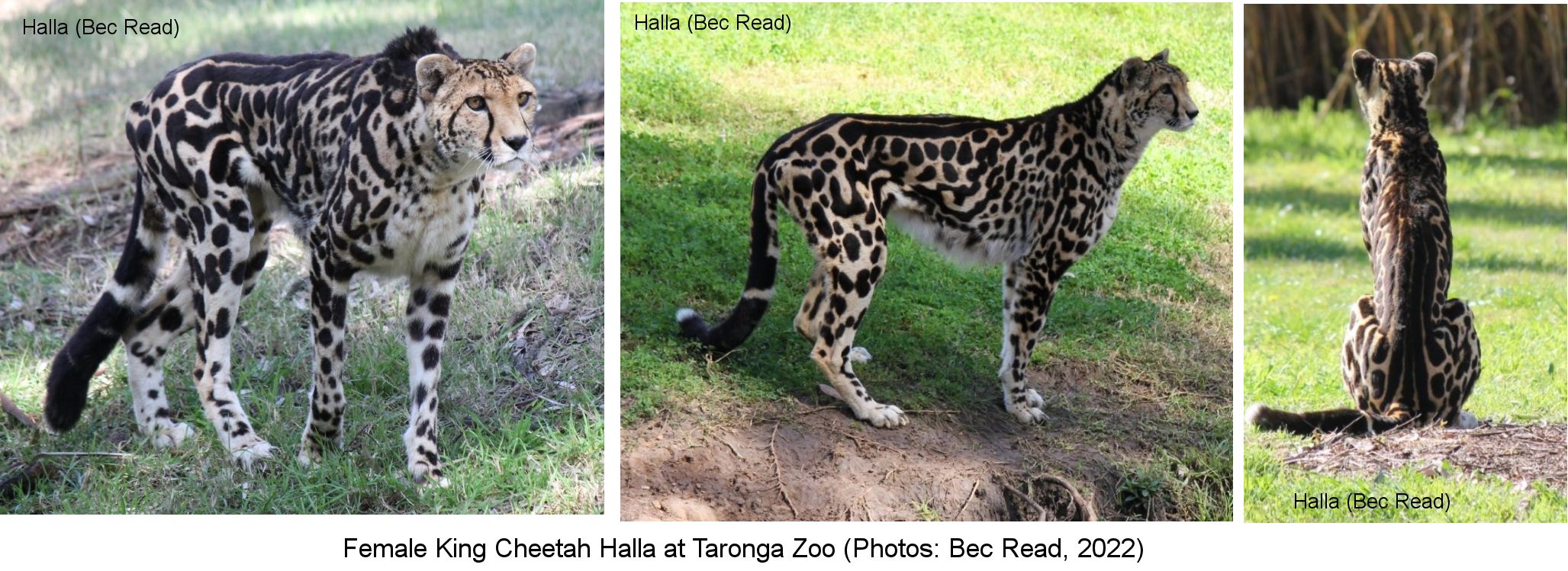

The king cheetah, a cheetah with black stripes along its back and swirls and splotches instead of spots was known to natives, but its existence had been pooh-poohed by white hunters and settlers. It was first noted by Westerners in Zimbabwe in 1926. In 1927, the naturalist Pocock declared it a separate species, but reversed this decision in 1939 due to lack of evidence. In 1928, a skin purchased by Lord Rothschild was found to be intermediate in pattern between the king cheetah and spotted cheetah and Abel Chapman voiced the opinion that it was a colour form of the spotted cheetah. 22 skins were found between 1926 and 1974. Since 1927, king cheetahs were reported 5 further times and though strangely marked skins had come from Africa, a live king cheetah was not photographed until 1974 in South Africa's Kruger National Park. Cryptozoologists Paul and Lena Bottriell mounted expeditions to find the king cheetah, finally photographing one in 1975. They also managed to obtain stuffed specimens. The king cheetah appeared larger than a spotted cheetah and its fur had a different texture.

Lists of known skins and reliable sightings, along with the non-lethal studies by Lena and Paul Bottriell between 1973 and 1979 established that king cheetahs derived from adjoininq portions of Zimbabwe, eastern Botswana, and the northern and eastern Transvaal of South Africa. When King cheetah cubs turned up in litters alongside spotted cubs in captivity, it was realised that the mutation was a recessive gene carried by some spotted cheetahs. There was another wild sighting in 1986 - the first for 7 years. By 1987, 38 specimens had been recorded, many from pelts.

King Cheetah early sightings and skins:

In 1926, a cheetah skin was discovered in southern Rhodesia having stripes and splotches in place of the usual spot pattern. It was purchased from native hunters and donated to the Queen Victoria Memorial Library and Museum in Salisbury. Museum authorities seemed unaware of the skin's significance until Major AC Cooper suggested it was evidence of hybridization between leopards and cheetahs. Cooper's curiosity sparked an investigation of the unusual pelt. He knew the native legend of the nsuifisi, a large cat "neither lion, leopard, nor cheetah" that preyed on the kraals at night. He learnt that the pelt had had come from the Macheke District of Zimbabwe, where this legend was strong. Cooper asked colonial officers throughout Zimbabwe to notify him of any further evidence of the nsuifisi's existence and the Native Commissioner at Bikita, in southern Zimbabwe sent photographs of two unusual cheetah skins from his district.

Cooper persuaded the Queen Victoria Museum to sent the Macheke skin to Reginald Pocock, curator of mammals at the British Museum in London. Pocock had earlier dismissed a photo of the find as being an aberrant leopard, but when he examined the skin itself, particularly the feet and claws, he realised it was a new kind of cheetah. In 1927, Pocock published an official description of acinonyx rex (King Cheetah) in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. As a result of the publicity, trophy hunters demanded a King Cheetah skin for their private collections. An unknown number of King Cheetah skins disappeared into the stores of taxidermists and into private collections. Pocock himself asked Cooper to find a skin for Lord Rothschild's collection (which is now part of the Natural History Museum). The two Bikita skins were purchased by the London taxidermy firm Messrs Rowland Ward Ltd who mounted them and sold them to museums in London and Natal. A similar selective slaughter of woolly cheetahs but hunters seeking unusual specimens had already wiped out one cheetah mutation.

In 1937, Captain W Hichens, Late of the Intelligence and Administrative Services, East Africa, wrote in African Mystery Beasts. (Discovery (Dec): 369-373) wrote: Nor is the African native a fool in the ways of the bushveld and its beasts; he does not assert that a beast is an mngwa when any old woman in the kraal could tell by a glance at its spoor or by the way it attacked that it is a lion, a leopard or a hyæna. Native hunting lore clearly dis-tinguishes the bush beasts. One well-known hunting-song tells of the simba (lion), nsui (leopard) and the mngwa all in one verse plainly showing that there is no confusion in the native mind between these three great carnivores. Moreover, many white hunters, settlers and officials, whose bona fides cannot be doubted, have spoored, heard, shot at and sometimes even seen and grappled with these mystery monsters; and very occasionally one of the "mythical" beasts is shot or trapped, as happened with the nsui-fisi recently. Then the natives say, "We told you so!" and zoologists scratch their heads and mutter, "ex Africa semper, etc.!"

[...]It is not impossible that the khodumodumo may yet prove to be an animal hitherto unknown. The nsui-fisi was a brute of a similar kind. Its name means " leopard-hyæna," and many hair-raising tales are to be heard of it in Rhodesian kraals. For many years natives have told white hunters of this beast, averring that it was incredibly cunning, swift and ferocious, as one would expect of a hybrid " killer" combining a leopard's ferocity with the hyæna's slinking guile. It always attacked, the kraalsmen said, at night, and smashed its way through the flimsy doors or roofs of stock-pens, making off with goats and sheep, and often turning the pens into a veritable shambles. It was like a leopard, the natives declared, but instead of being spotted, it was barred, white and black, like a zebra, and not unlike a striped hyena. But no such beast was known to white hunters and so the nsui-fisi was pooh-poohed into the limbo of "it's just native superstition, of course!"

In this case, however, the native was right. No less an authority than Mr. R. I. Pocock was able to lay on the table of the Zoological Society not long ago, a skin of the nsui-fisi, one of a number obtained in Rhodesia. It was shown to be a new species of cheetah (Acinonyx rex), not spotted, but striped like a zebra, as the kraalsmen had been saying for many years! As Mr. Pocock remarked, it was "most extraordinary that so large and distinct a species should remain for so long unknown." The natives were wrong in supposing the nsui-fisi to be a leopard-hyaena cross, but that is certainly what it looks like to anyone other than a skilled zoologist. It would thus be rash to assert that other "mythical beasts" like the nsui-fisi cannot exist, and it is by no means impossible that the mngwa, kerit, and ndalawo may yet prove to be as real. By description all these beasts are well known.

The question of its identity was resolved (for Europeans) in the 1981 when king cheetahs were born to spotted cheetah parents at the De Wildt Cheetah Centre (Ann van Dyk Cheetah Centre) in South Africa. In May 1981, two sisters gave birth there and each litter contained one king cheetah. The sisters had both been mated to a wild-caught male from the Transvaal area (where King Cheetahs had been recorded) and further King Cheetahs were later born at the Centre. The gene is recessive, meaning it is carried hidden in some spotted cheetahs. When two carriers mate, there is a chance that some offspring will inherit two copies of the hidden gene and be king cheetahs. King cheetahs mated together will produce king cheetahs. This cheetah mutation has been reported in Zimbabwe, Botswana and in the northern part of South Africa's Transvaal province. There are probably only a handful of king cheetahs in the wild, but it has been bred in captivity. As with the selective breeding of white tigers and white lions, there is a danger of inbreeding - since cheetahs are already so inbred (causing infertility problems), this could be disastrous. The king cheetah is disadvantaged when stalking prey on the open plain, but less so in areas where it can begin its sprint from dappled shade.

Most king cheetahs in zoos appear to originate from the Ann van Dyk Cheetah Centre, a captive breeding facility for South African cheetahs. In the USA, AZA zoos aren't allowed to exhibit king cheetahs. They are in the same category (freaks) as white lions, white tigers, and black leopards and black jaguars because they can be selectively bred to attract the public rather than for conservation. This seems short-sighted as they could be allowed to occur at a similar rate as they do in the wild.

In February 2021, a King Cheetah was seen in the wild, 9 km east of Pretoriuskop Camp, Kruger Park.

King Cheetahs GenealogyIt is recomend this chart be viewed at high magnification as it is complex and large!

WOOLLY CHEETAHCheetahs with longer, denser fur have occurred several times and were thought to be a separate species. They were shot rather than captured alive so the mutation has vanished. They had thicker bodies and stouter limbs than normal cheetahs (this may be a trick of the long hair) with dense, woolly hair especially on the tail and neck where it formed a ruff or mane. The long fur made the normal spotted cheetah pattern indistinct and it appeared pale fawn with dark, round blotches. In domestic cats, the markings of longhairs are less distinct than those of shorthairs due to the blurring effect of longer fur. In domestic cats, long hair is due to a recessive gene, so the gene may still be present in the cheetah gene pool. The cheetah gene pool, however, is not as diverse as the gene pools of most other cat species. The painting of the woolly cheetah (shown below) suggests not only a longhaired cheetah, but a red (erythristic) cheetah.

From the Secretary’s [Philip Sclater] Report, Proceedings of the Zoological Society, June 16, 1877:- An animal sold to us on the 29th May by Mr. Arthur Mosenthal as a Cheetah, but which appears to belong to a new species of the genus Felis, distinct from, although closely allied to that animal. It is a male, probably not quite fully grown. It presents generally the appearance of a Cheetah (Felis Jubata), but is thicker in the body, and has shorter and stouter limbs, and a much thicker tail. When adult it will probably be considerably larger than the Cheetah, and is larger even now than our three specimens of that animal. The fur is much more woolly and dense than in the Cheetah, as is particularly noticeable on the ears, mane and tail. The whole of the body is of a pale isabelline colour [yellowish-fawn], rather paler on the belly and lower parts, but covered all over, including the belly, with roundish dark fulvous blotches. There are no traces of the black spots which are so conspicuous in all the varieties of the Cheetah which I have seen, nor of the characteristic black line between the mouth and eye.

Until we know more about this animal, and further examples of it have been obtained, it is perhaps too early to say that we have here a new species amongst the larger Cats; but after having looked through the descriptions of the varieties of the Cheetah given by different authors, and having especially studied the descriptions of the Felis jubata and F. guttata, as distinguished by Wagner, I believe it impossible to associate the present animal with any of them, and I propose to give it the temporary designation of Felis lanea or Woolly Cheetah. Mr. Mosenthal informs me that this animal, though shipped at Cape Town, was originally procured from Beaufort West in the Cape Colony. It is difficult to understand how such a distinct animal can have so long escaped the observations of naturalists.

Mr. Bartlett, by whom my attention was first directed to it, tells me that he has examined many Cheetah's skins from Africa, but never saw one anything like that of the present animal. We have had in the collection Cheetahs from South Africa, Eastern Africa, Syria, and India, and have no doubt they all belong to one species. At the present moment we have in the Gardens examples of both African and Indian forms.

Mr. Smit's drawing (Plate LV.), together with the preceding notes, will, I trust, serve to make the differences between Felis lanea and F. jubata intelligible to naturalists.

[At first one might be inclined to suppose that our animal was the Felis jubata of Duverny (Mem. Mus. d'H. N. Strasbourg, ii. p. 10), as distinguished by him from Felis guttata, as follows:- (Translated) “The felis jubata is distinguished by a nanking yellow dress dotted everywhere, even under the belly, with round spots, dark in colour.It is further so by its thicker form and a rather strong mane. The felis guttata differs from it by a slender shape, taller legs, its coat of a dark or light orange fawn, dotted with round black spots, except below, where it is sometimes pure white and without any markings or only dull markings." But on looking more narrowly into Duvernoy’s description, particularly to his reference to the black line below the eye in his F. jubata, I think it impossible to identify it with the present animal.]

From the Secretary’s Report, Proceedings of the Zoological Society, June 18, 1878:- Mr. Sclater called the attention of the members present to the unique specimen of his Felis lanea (P. Z. S. 1877, p. 532), still living in the Society's menagerie, and read the subjoined extract from a letter of Mr. E. L. Layard, F.Z.S., relating to this animal:-

" It will interest you to know that there is a second specimen of your Felis lanea in the South-African museum, sent from the same place (the Beaufort-West Karras) by the late Arthur V. Jackson, who killed it himself. Unfortunately I received the skin in very bad condition. The ground-colour is much paler than in your plate, almost white. Jackson and I thought it an albinism (or rather erythrism) of F. jubata (see Catalogue of S. A. Museum, p. 38, No. 82, Gueparda jubata, specimen b). At p. 39 of the same Catalogue, I remark that we have had notices of a second species of Maned Leopard [cheetah], with solid spots and with retractile claws, from Natal. The claws of your animal are not shown in Smit's plate. What is their structure?"

On this last point Mr. Sclater stated that, so far as could be told from examination of the living animals, the claws of Felis lanea resembled those of Felis jubata, being observable when the feet were at rest, and being but slightly extensile. The existence of a second specimen of the animal in the South-African Museum (of which Mr. R. Trimen had also informed Mr. Sclater) was a fact of great interest.

Proceedings of the Zoological Society, Nov 4, 1884.:- Mr. Sclater exhibited the flat skin of a Cheetah, obtained at Beaufort West, South Africa, and forwarded to him by the Rev. G. H. R. Fisk, C.M.Z.S. Mr. Sclater observed that this skin agreed nearly with that of the animal formerly in the Society's Menagerie and described and figured by him in P. Z. S. 1877, p. 532, pi. lv., as the Woolly Cheetah (Felis lanea), the skin of which is now in the British Museum. It was, however, rather smaller in size and more distinctly spotted, and perhaps not quite so densely furred, owing probably to the fact that the animal was, as Mr. Fisk believed, a female. Mr. Sclater was of opinion that this skin went to corroborate the existence of Felis lanea as a valid species, although he was assured by Mr. Oldfield Thomas that the skull of the specimen formerly in the Society's Gardens did not differ from that of the ordinary Cheetah.

Proceedings of the Zoological Society, May 3, 1887:- "The case [. . . ] seems much to resemble those of the singular form of Cheetah (Felis lanea of Sclater), of which only five specimens are known, all from the very limited area of Nel's Point, in the Beaufort District of the Cape Colony, and the equally aberrant Leopard (F. pardus, L., var. melas ; see Trimen, P. Z. S. 1883, p. 535, and Gunther, P. Z. S. 1885, pi. xvi. p. 243), of which only three examples are known, from the neighbourhood of the Koonap River, in the Fort-Beaufort District on the eastern side of the Cape Colony. It is very noticeable that, in all three cases, the abnormal form does not replace the normal one to which it is so nearly related, but occurs in the midst of the latter, quite isolated, yet appearing to maintain and perpetuate (albeit in but very few individuals) its peculiarities of colouring or of pattern."

All of the specimens had come from Beaufort West. Sadly, trophy hunters seem to have eliminated the woolly cheetah.

In Harmsworth Natural History (1910), R Lydekker wrote of the "hunting leopard" or "chita", as the cheetah was then known: "The hunting leopard of South Africa has been stated to differ from the Indian animal in its stouter build, thicker tail, and denser and more woolly fur, the longest hairs occurring on the neck, ears, and tail. This woolly hunting leopard was regarded by its describer as a distinct species (Cynaelurus lanius), but it is, at most, only a local race, of which the proper name is C. jubatus guttatus."

WHITE, BLUE (GREY), CREAM & BLACK CHEETAHSThe Moghul Emperor of India, Jahangir, recorded having a white cheetah presented to him in 1608. “The Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri or Memoirs of Jahangir “was translated into English by Alexander Rogers and edited by Henry Beveridge, and published between 1909-1914. The description of the white cheetah is in Vol 1, pp. 139-40. ”In the third year of his reign (1608 A.D.), the Emperor records the following event: ‘On this day Raja Bir Singh Deo brought a white cheeta to show me. Although other sorts of creatures, both birds and beasts, have white varieties, which they call tuyghan, I had never seen a white cheeta. Its spots which are (usually) black, were of a blue colour, and the whiteness of the body was also inclined to bluishness. Of the albino animals that I have seen there are falcons, sparrow-hawks, hawks {Shikara) that they call bigu in the Persian language, sparrows, crows, partridges, florican, podna {Sylvia olivacea) [sic.], and peacocks. Many hawks in aviaries are albinos. I have also seen white flying mice (flying squirrels) and some albinos among the black antelope, which is a species found only in Hindustan. Among the chikara (gazelle), which they call safida in Persia, I have frequently seen albinos.” Jahangir refs to the cheetah as white, rather than albino, and the description sounds like a chinchilla mutation, where the spots appear silvery-blue on a pale silvery/bluish background. There seems to be no other information about this creature (perhaps further information exists, but has not been translated), though it has been hypothesised that Raja Bir Singh Deo acquired it in the jungles of his Bundelkhand home region.

The bluish colour, and the whiteness of the body, which also inclined to blue-ishness indicates the chinchilla mutation which restricts the amount of pigment on the hair shaft. Although the spots would have been formed of black pigment, the less dense pigmentation (it does not go all the way to the root of the hair) would have produced a hazy, bluish effect. As well as Jahangir's white cheetah at Agra, a report of "incipient albinism" has come from Beaufort West according to Guggisberg. The two sketches below show an isabelline cheetah and a maltese (blue) cheetah ("isabelline" means yellowish-fawn; maltese means "slate grey").

|

Isabelline Cheetah |

Albino cheetah and maltese cheetah |

Red (erythristic) cheetahs have dark tawny spots on a golden background. Cream (or isabelline) cheetahs appear to be a further dilution of red with pale red spots on a pale background. Blue (or grey) cheetahs have variously been described as white cheetahs with grey-blue spots (chinchilla) or pale grey cheetahs with darker grey spots (maltese mutation). Some desert region cheetahs are unusually pale; probably they are better camouflaged and therefore better hunters and more likely to breed and pass on their paler colouration. Below is a cream cheetah with reddish spots.

As well as the possibly red longhaired cheetah shown here, different coloured cheetahs have sometimes occurred. Melanistic (black) and albino (white) cheetahs have been reported. Black cheetahs are all black with ghost markings (Stoneham, 1925). In a letter to "Nature in East Africa", HF Stoneham reported a melanistic cheetah in the Trans-Nzoia District of Kenya in 1925. Vesey Fitzgerald saw a melanistic cheetah in Zambia in the company of a spotted cheetah.

Stylised black cheetah image |

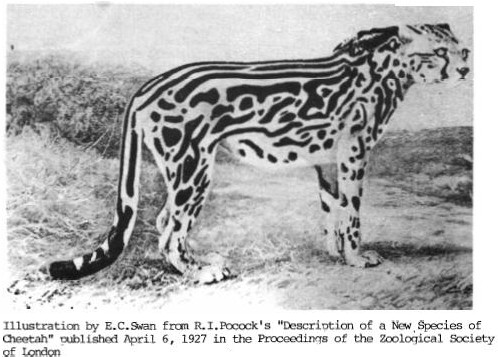

SPOTLESS CHEETAH

A cheetah with hardly any spots was shot in Tanzania on 1921 (Pocock), it had only a few spots on the neck and back and these were unusually small. This is possibly the same mutation which causes ticked (Abyssinian-type pattern) cats; any markings are restricted to the face, legs and tail with possibly some thin stripes around the neck and barring on the legs. The background colour remains the normal colour, it is just the pattern which is missing.

A spotless cheetah or golden cheetah was photographed in Kenya in 2011. It had the black "eyeliner" markings on the face, but instead of a spotted coat it had a pale sandy coat (akin to a puma) with freckles confined to the dorsal area. This is a colour morph, due either to a new mutation or to an existing recessive gene mutation carried in the local cheetah population. The presence of black facial markings and small, pale spots meants it is not an albino or leucistic cheetah. It's appearance matches the description of the spotless cheetah shot in Tanzania in 1921. The latest golden cheetah was photographed in an area between Amboseli and Nairobi where there is a high cheetah population. The appearance of unusual cheetah morphs suggests improved genetic variability (through mutation) in the species.

Cheetahs show less variety in their type than do many other types of big cat due to a genetic bottleneck. The DNA of all modern cheetahs is so similar that it is thought that all cheetahs are descendants of a single mother and cubs. This inbreeding means little genetic variation, poor fertility and increased susceptibility to disease. The appearance and perpetuation of the blotched (king) cheetah is highly significant as it suggests that gene mutations are occurring and that cheetahs may become more genetically diverse in the future.

Textual content is licensed under the GFDL.

For more information on the genetics of colour and pattern:

Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders & Veterinarians 4th Ed (the current version)

Genetics for Cat Breeders, 3rd Ed by Roy Robinson (earlier version showing some of the historical misunderstandings)

Cat Genetics by A C Jude (1950s cat genetics text; demonstrates the early confusion that chinchilla was a form of albinism)

For more information on genetics, inheritance and gene pools see:

The Pros and Cons of Inbreeding

The Pros and Cons of Cloning

For more information on anomalous colour and pattern forms in big cats see

Karl Shuker's "Mystery Cats of the World" (Robert Hale: London, 1989 - some of the genetics content is outdated)

|

BACK TO HYBRID & MUTANT BIG CATS INDEX |