HAGENBECK - ANIMALS AND PEOPLE (1909)

Adventures and experiences of Carl HagenbeckDedicated in deepest reverence to His Majesty the German Emperor and King of Prussia, Wilhelm II, by the author.

Contents

Foreword

First Section

l. Memories From My Youth

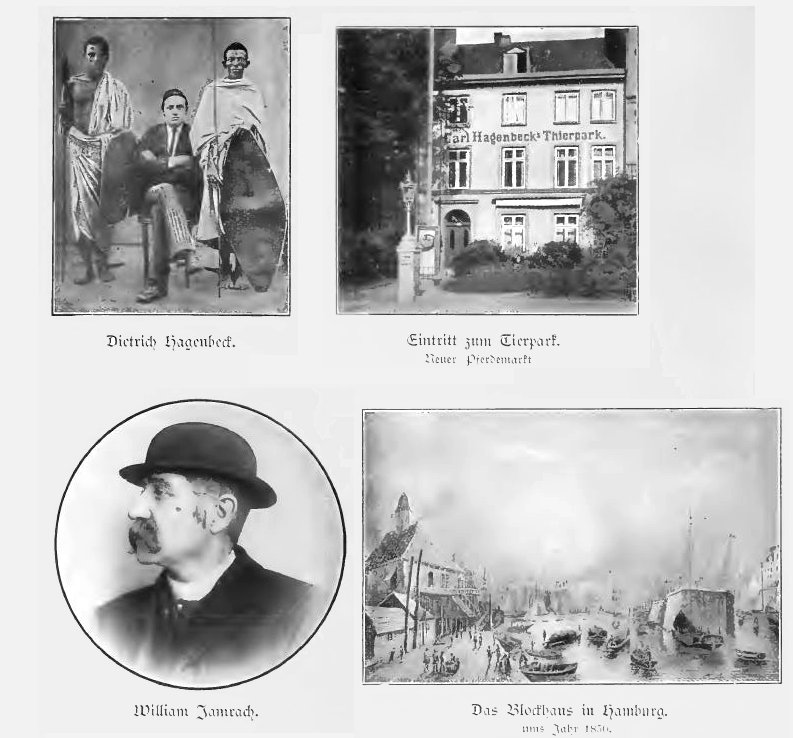

Il. Development of the Pet Trade

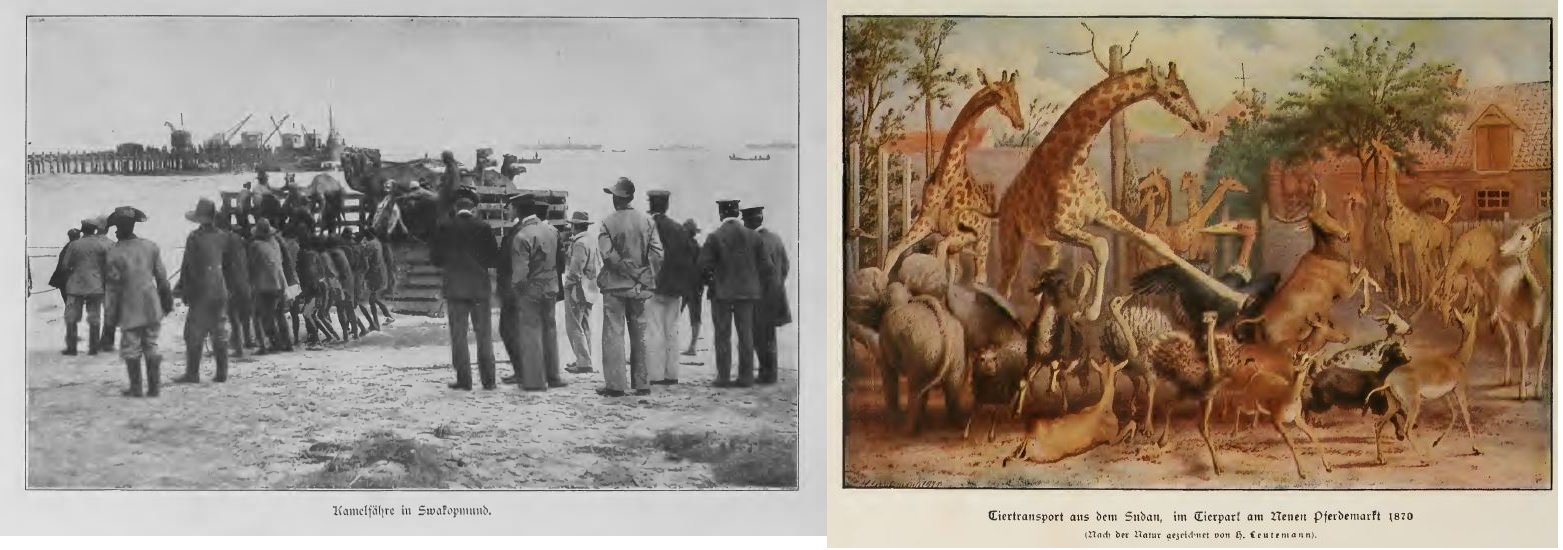

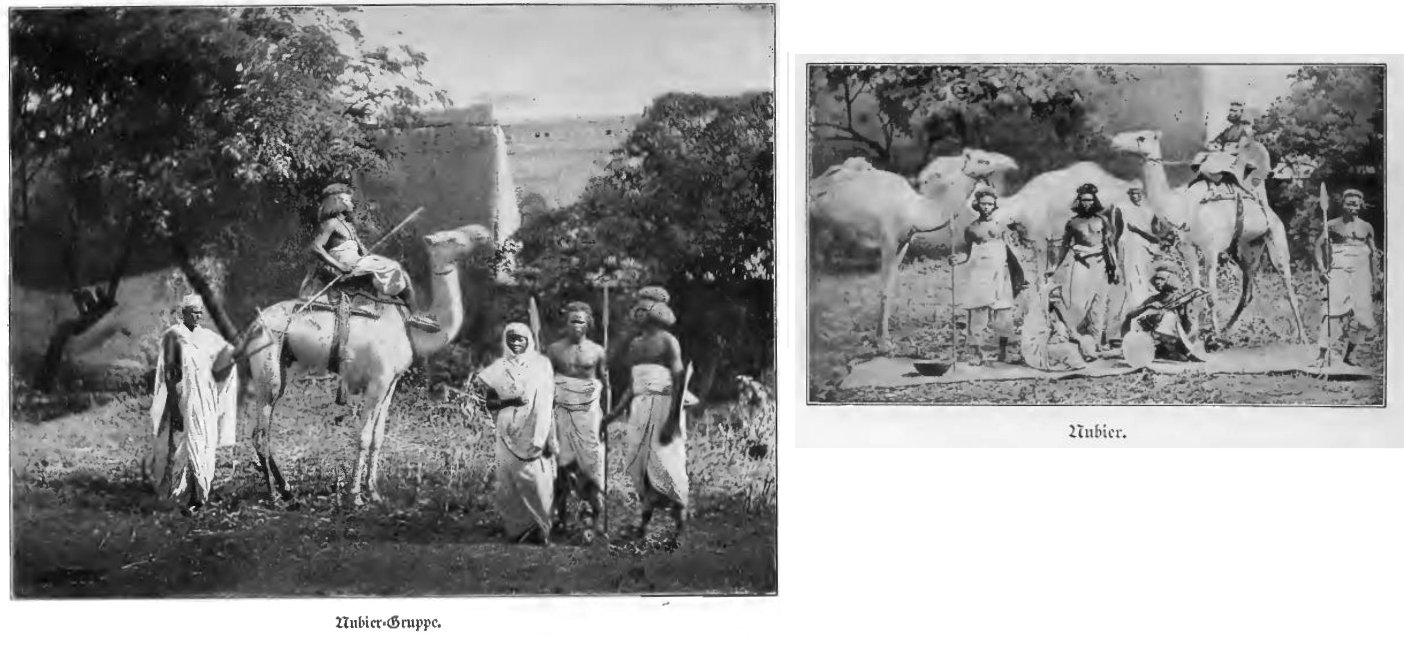

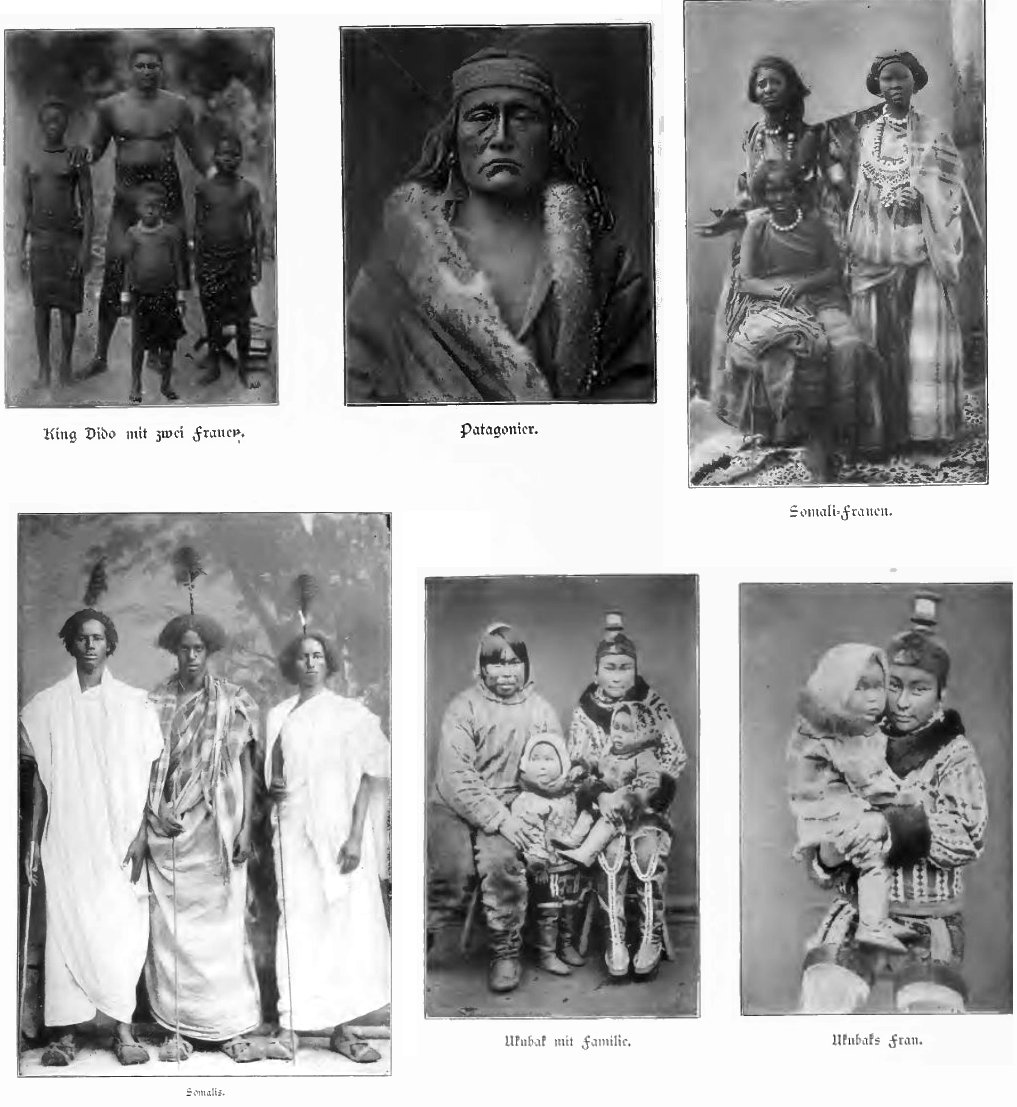

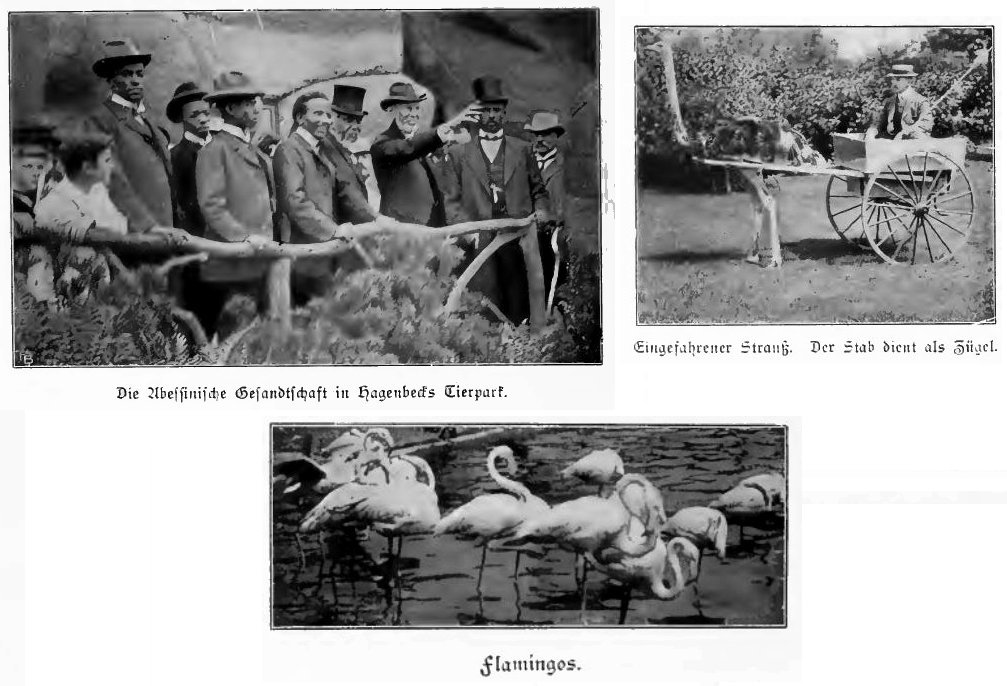

III. Exhibitions of People

IV. I Decide to be a Circus Director and Animal Tamer

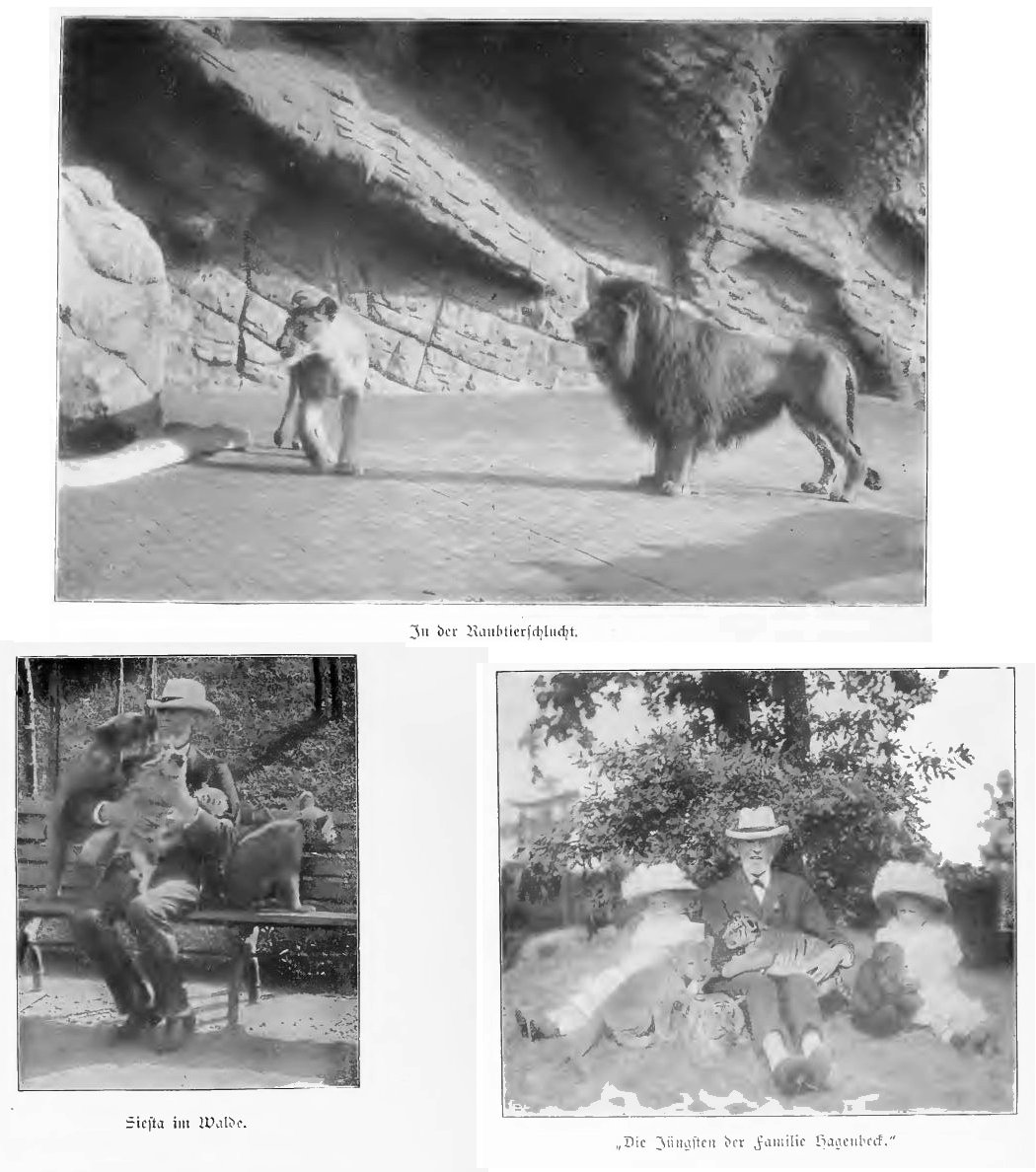

V. Creation of the Animal Paradise

Second Part

I. Regarding the Capture of Wild Animals

ll. Captive Predators

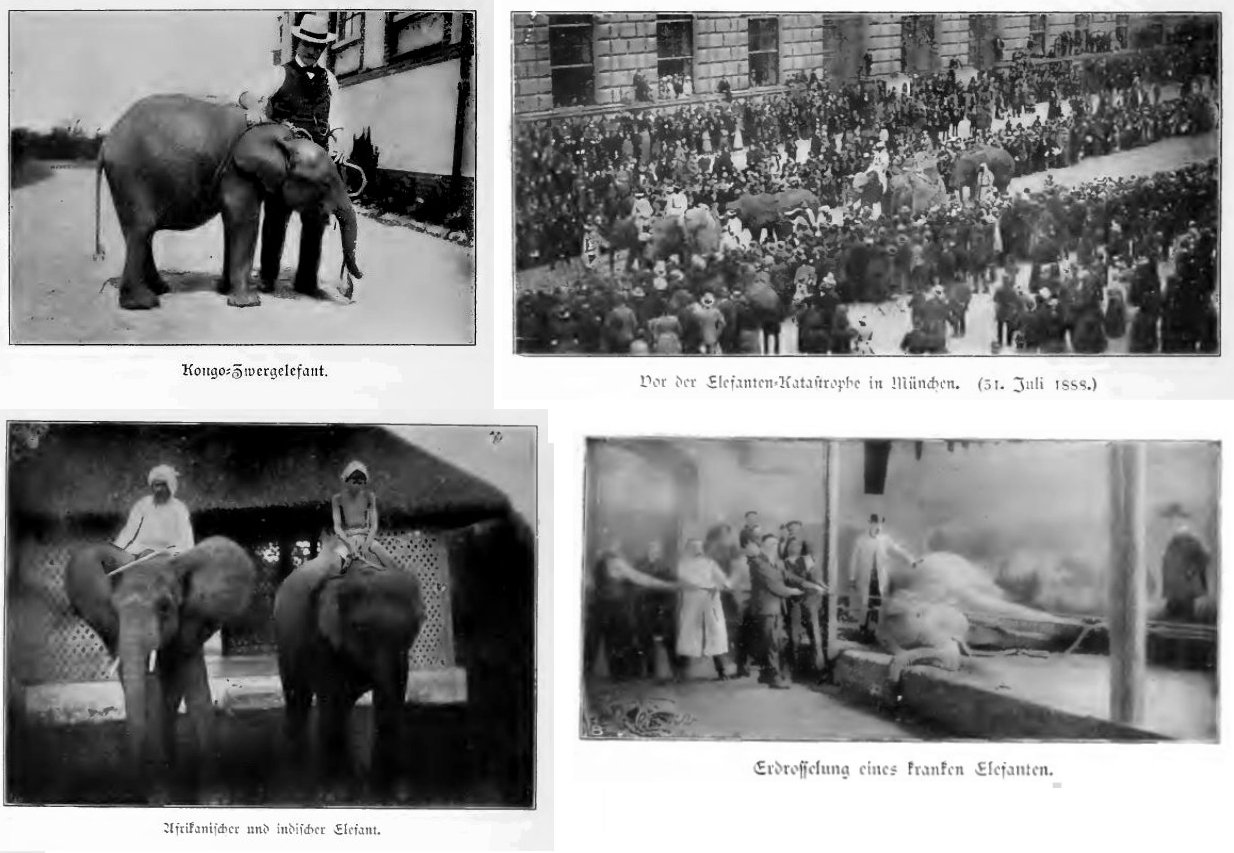

III. Elephant Memories

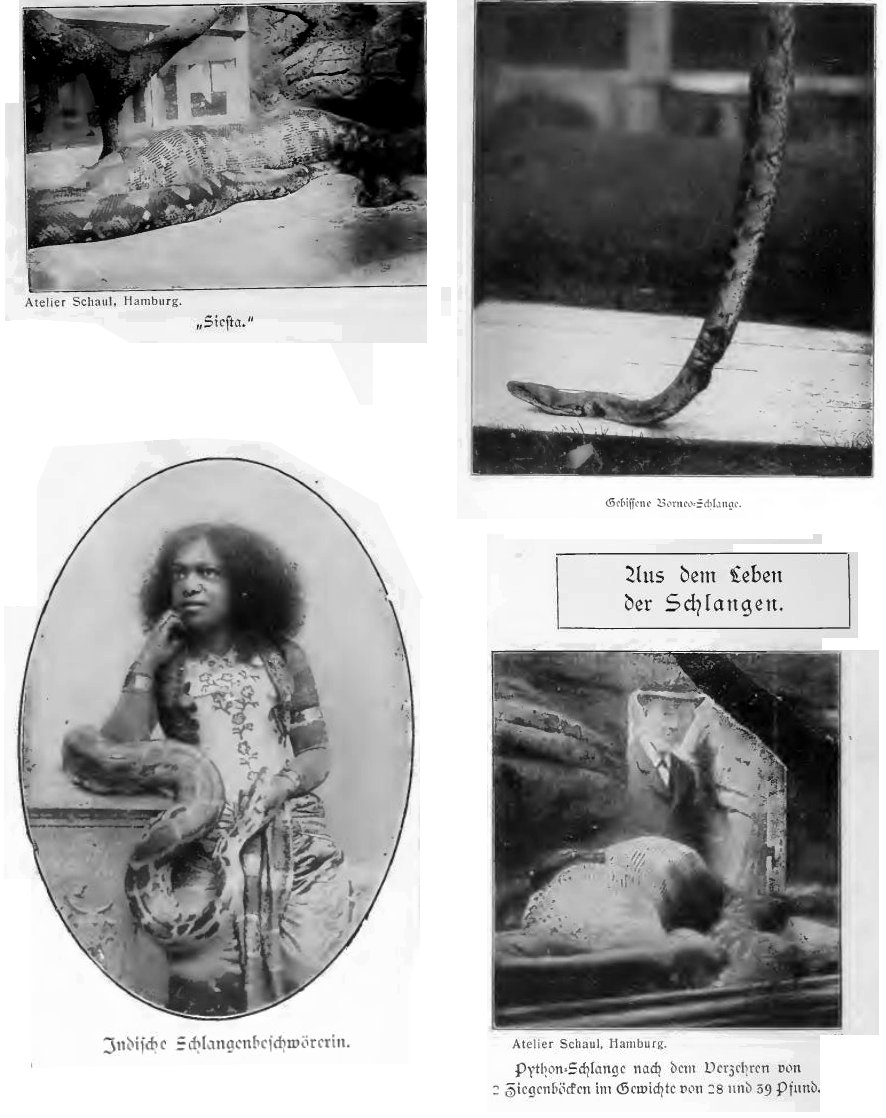

IV. Snake Stories

V. Little Adventures

Vl. Training Wild Animals

VII. Regarding Breeding and Acclimatization

VIII. Treating Sick Animals

IX. Notes About Stellingen

X. Great Apes

Third Section

l. People

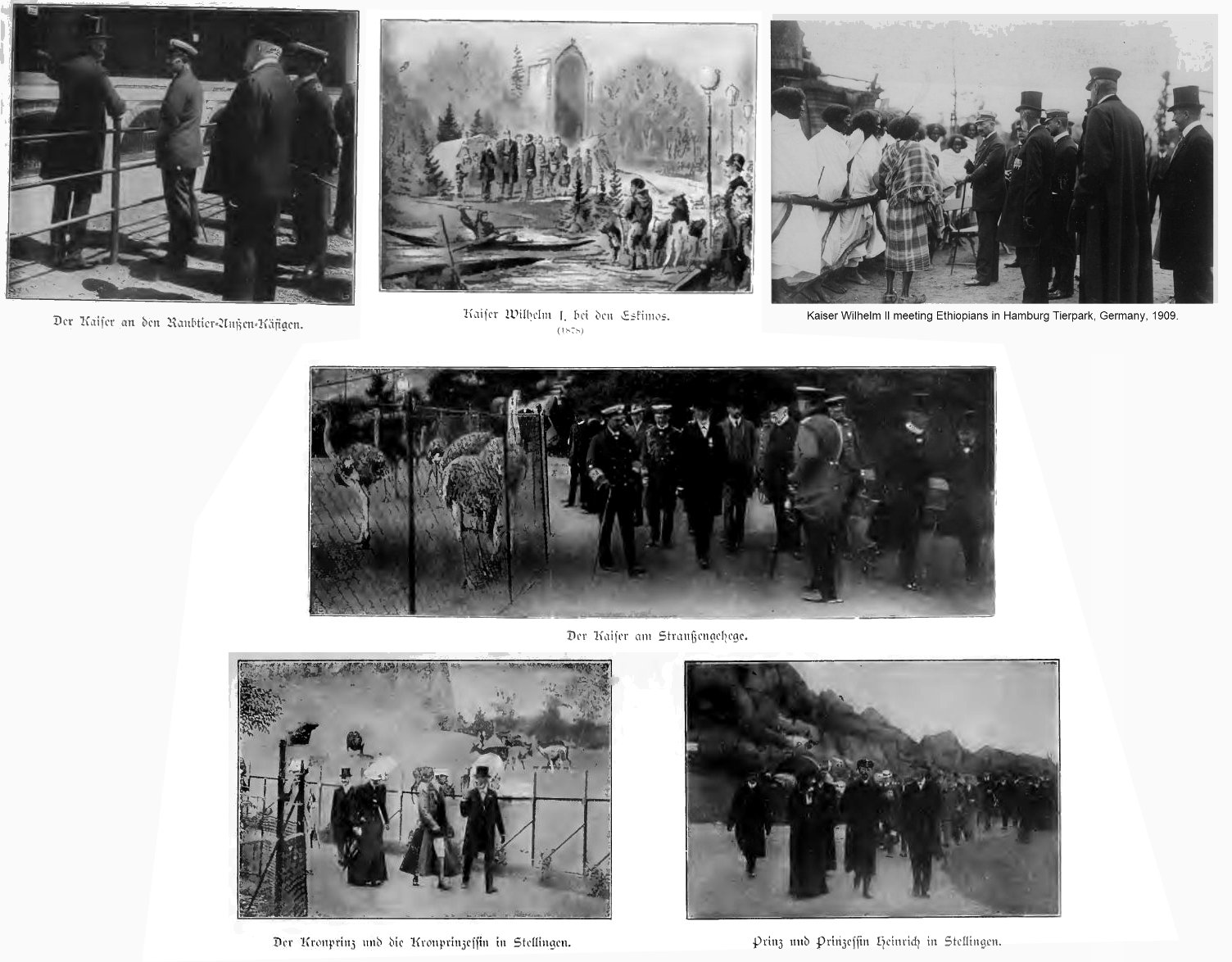

ll. Kaiser Wilhelm II. Visits Stellingen

Addendum

The Summer of 1909

In addition to this edition, a luxury edition of this work was published on art paper in half French-bound with leather pressing at a price of M.15 - and a collector's edition in two full leather volumes at a price of M. 100.

FOREWORD TO THE NEW EDITION.

The great and enduring success of my memoirs makes me proud and happy. When I wrote the book, it was not my intention to create a 'business', but to tell the world how many sacrifices have been made to achieve the modest successes that I can look back on. But things turned out very differently, my wildest expectations were exceeded and many thousands of fellow combatants in the arena of life reached out and assured me that they understood me. If the description of my life's work has shown what diligence and perseverance can achieve, and if the love of the animal world is encouraged by the distribution of my book, then I am satisfied with the seed that this work has sown.

I feel particularly honoured and deeply delighted by the suggestion received from a wide variety of circles to follow up the first edition of my book with a new, cheaper edition, so that it - undeservedly, I believe - can have a greater distribution. I gratefully place this new edition in the hands of my readers.

Carl Hagenbeck

FOREWORD TO THE FIRST - ELEVENTH ISSUES.

My whole life was spent in practical work. For the first time I am trying to use these notes to move from the realm of deeds to that of words. I am not a practiced writer and must beg the indulgence of literary experts and the public alike. I hope that the factual material contained in the following pages will compensate for its style, as I certainly could not do it justice to with this, my first and probably my last, book. But my hope is also based on the fact that I have found self-sacrificing and tireless support in literary matters from my old friend and adviser, the well-known author Mr. Philipp Berges, and my energetic publisher, Mr. Felix Heinemann, owner of the Vita publishing house, with valuable suggestions and personally offered assistance in the development of this work. I am sincerely indebted to both gentlemen now that this work lies finished before me, to my delight.

Hamburg-Stellingen, October 1908.

Carl Hagenbeck.

FIRST SECTION

The world had not yet been dominated by traffic when I was a boy. The noise and hustle and bustle that now fills the cosmopolitan city of Hamburg was not yet noticeable. Along with the Senate crier swinging his big bell, the strangest characters strolled through the streets of jolly old Hamburg. Somewhere in the suburbs the merry hustle and bustle of a fair took place almost every season, and around Christmas almost all the vacant squares in the city were given over to the famous "Hamburger Dom" [a funfair], which has since lost much of its originality. When I now let my gaze wander over the wide grounds of the Stellingen zoo, with its green meadows and towering artificial mountain formations, between which thousands of visitors enjoy the sight of the living animal panoramas, it almost seems like a dream to me that the old Hamburger Dom is solidly linked to the animal paradise of Stellingen.

I can still clearly see the Großer Neumarkt as it looked at Christmas time, covered with snow-covered stalls. Hands in pockets, hopping from one foot to the other from the cold, the young people crowded in front of the tempting displays of sweets, toys and fragrant fried pastries, but even more in front of the mechanical theatres, waxworks and stalls with cannibals and rare animals. On the old cathedral you could still, in all seriousness, see the mermaids and similar mythical creatures in person. In front of the stalls the criers, called barkers, walked hastily up and down, for they too were freezing, and loudly called out in inviting voices. One of them was the "performer" Schwanenhals or, as he called himself, Swonenhals, an eccentric person who was recruited for all kinds of services. So now, on a winter evening in 1853, Swonenhals was pacing up and down in front of a show booth on the Großer Neumarkt and kept calling out these memorable words to the astonished audience:

"Walk in, gentlemen! Here you can see: the largest pig in the world! You must view something like this, it's colossal, it's unbelievable, it's unprecedented! The giant pig, gentlemen, can be personally inspected here. Adults pay one shilling, children half!"

This text was supported by a huge sign on which the pig was depicted as large as a hippopotamus. But, for me, the strangest thing about this booth on the old Hamburger Dom was the fact that this primitive enterprise also bore the name Hagenbeck! This or another similar display from bygone times was the root from which this widely branched company, now centralized in Stellingen, grew up and was baptised half a century ago.

The entrepreneur who presented the giant pig to an admiring public at the Grosser Neumarkt was my dear father, who had bought the animal, which indeed weighed nine hundred pounds, from an old veterinarian. In those years my father was in the habit of never letting the Cathedral period pass without exhibiting some rare or remarkable animal phenomenon. There were, of course, the most amusing deceptions which have become quite impossible today and which one would no longer attempt with impunity even in an American dime museum. One day my father was offered a Vicuna llama by the captain of a ship that had arrived in the port of Hamburg; this was immediately bought for 60 thalers and destined for public display. All the preparations were made and, among other things, a large flaghead was ordered from old Rialer Gehrts, but - oh dear! Before the new attraction could be put on display, it died. The llama died. What on earth could he do? Put the expensive sign that cost twelve thalers in a corner? Impossible. A new vicuna had to be hunted down in the fields of Hamburg for the shield. My father found one in the form of an ordinary, very local deer, which he bought and quite brazenly exhibited to the visitors as a llama. At that time, one could allow oneself such hoaxes without a second thought as people were not as well versed in zoology as they are today, one got one’s knowledge from travelling menageries, who allowed themselves completely different fakeries.

The beginning of the animal business, insofar as it is connected with my house, dates back even further. As for myself, I can say that my whole life, from the cradle onwards, has been directly connected with the animal world, for my father operated a fish shop in the Hamburg suburb of St. Pauli, where I was born on June 10, 1844. The animal trade grew directly from this. But one shouldn't draw any wrong conclusions from his little cathedral swindle, which meant nothing in jolly old Hamburg. The famous "Hamburg at night" stall emerged from the cathedral, into which visitors were let in at the front for a fee of one shilling and then simply let them out at the back, onto the street, and there they had Hamburg at night.

I recall my father as an upright, sharply defined character. He was a man of unshakable principles and strong points of view. I will say with great satisfaction that he laid the foundation for everything that has been achieved. In his character he was very serious about life and had a friendly manner. His saying at all times was "With a hat in your hand you can get through the whole country." The practical application of this saying was made clear to me so often as a boy that it became instilled in my flesh and blood, and I have, I believe, passed it on to my family. Behind my father’s extreme strictness in the upbringing of his children, there was a great goodness of heart. The cane played its role in our upbringing, and through our father’s example, made up entirely of activity, punctuality and thrift, we children learned to live in his spirit. Only once do I remember being beaten; Father called me and I still didn't get to the table in time. Since then I have become accustomed to strict punctuality. If there was a fight between the children, a loud "Hello, hello!" or a "Nana!" was enough and everything went quiet. In particular, we were encouraged to save, nothing that could be of any value was allowed to go to waste. For example, the nails that bent when the crates were opened were knocked straight and used again. As a kind of talisman my father always carried in his pocket the first large coin he had earned in his youth, and as a dear legacy this old coin is now my constant companion. For the work that we children had to do in the shop from an early age, we received a fixed payment, which each child had to put into a clay piggy bank. At Christmas these money boxes were smashed and the money exchanged for silver and gold ducats. I still own mine today.

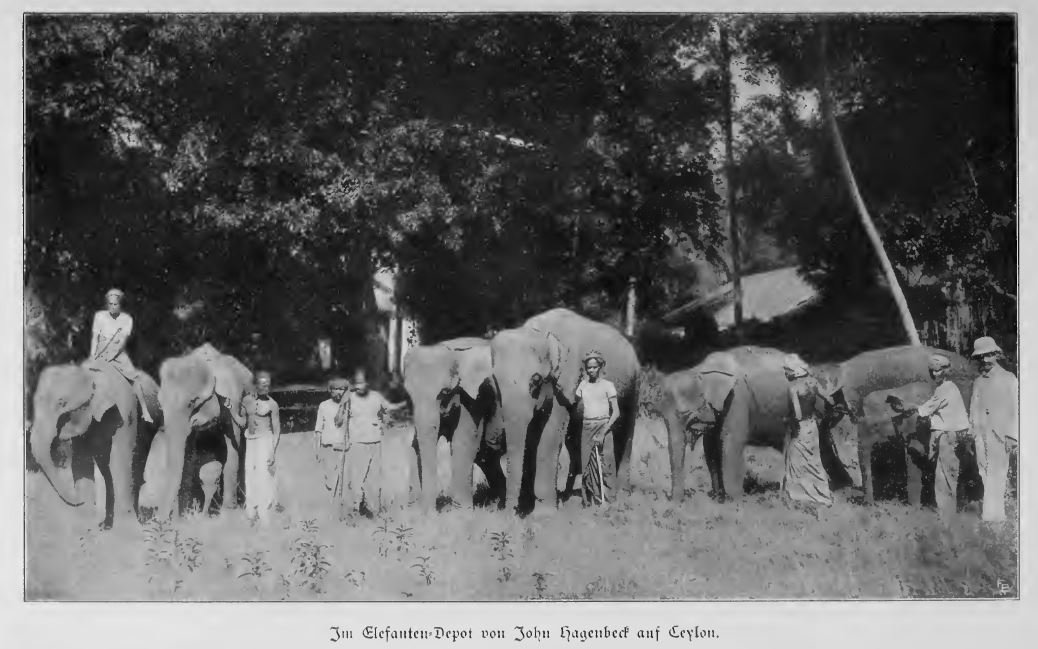

We were three boys and four girls, of whom, myself, my brother Wilhelm and my sister, Mrs. Runde, are still alive. My mother died in spring 1865. Through my father’s second marriage later on, I have two half-brothers, John Hagenbeck in Colombo on Ceylon and Gustav Hagenbeck in Hamburg.

My entire busy boyhood was spent between the fish business, which grew from small beginnings to a large concern, and the incipient pet trade. I only went to school when there was time, at most three months a year. Elementary learning was drummed into me at a girls' school, at Mother Feind's on Friedrichstrasse in St. Pauli, and it was not until I was twelve that I attended school more regularly. My father was by no means against the blessings of education, and a certain amount seemed absolutely necessary to him, but he valued early, practical acquisition just as highly, in keeping with today’s American spirit. He used to say: "Pastors never work, but they must read and write!"*) Later, when the flourishing business established connections with France and England, my father's broad view proved its worth, and it was said, "That's not enough, you must also learn English and French." In the few remaining school years, the foundations were laid for the higher subjects and also for languages, but in the main the knowledge necessary for extensive business participation was acquired from that great school called "practical life."

(* Pastoren sollt Ihr nicht werden, aber rechnen und schreiben müßt Ihr können.)

The main activity in the fish business was during summer. That was when the sturgeons, which are now extremely expensive, were coming onto the market in large numbers and my father was one of the main buyers. He retained a large number of fishermen in his service for a fixed salary, who had to deliver everything they caught in their nets. From March to July, fish moved from the sea up the Elbe to spawn and to unwillingly be caught in long, large nets. We bought and processed an average of 4,000 – 5,000 sturgeons each season. Processing means extracting the caviar and smoking the meat. The modern reader, who cannot dig deep enough to meet the needs of life, will surely be interested to learn the prices of the time. A pound of smoked sturgeon meat was already considered expensive if it cost with 4 - 5 Hamburg Schillings, which is 32 - 40 Pfennigs in today's money. Nowadays a pound of sturgeon meat costs 2.50 to 3 Marks, that is to say much more. The price for an ordinary milt sturgeon was then 3 to 4 Marks and roe sturgeons cost 10-12 thalers each, depending on their size. I know all this not only from hearsay, but because I was already in the middle of the business when I was a ten-year-old boy, and I still think back with pleasure to some episodes from that time. How many times have I gone out with the fishermen to catch and, with my boyish hands, have helped pull the colossi, armoured with hard scales, out of the nets. Once, near Glückstadt, we caught a giant specimen, which was an impressive thirteen feet in length and strength to match. Retrieving the colossus, into whose back the fishermen hammered a hook or so-called "fang", became a struggle. The prey turned out to be a roe sturgeon which yielded two and a half buckets of caviar. At that time, roes cost 10 - 12 Prussian thalers per bucket (15 litres). My fondness for the sea and deep-sea sport fishing, can perhaps be traced back to the early hunting trips and recently almost cost me my life on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea while hunting sharks. A storm took our boat by surprise, and if we hadn't reached the harbour at the last moment, rushing out of the lashed waves ahead of the hurricane, these youthful memories of our first hunting trips along the water would have vanished too.

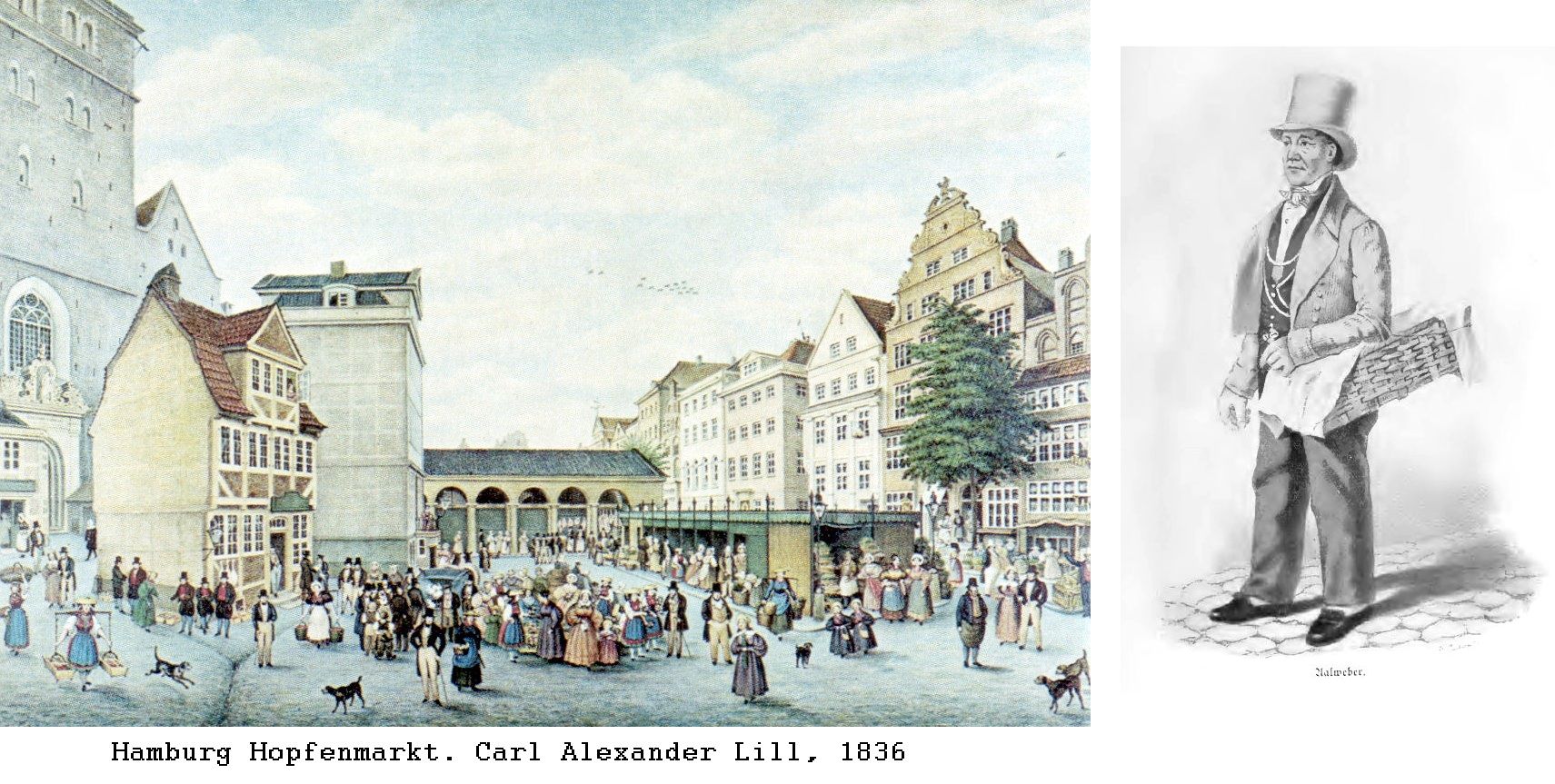

But my boyhood was not spent on the water. Many a day I bought fish for 100 thalers and more on my own at the Hamburg Hopfenmarkt, where people still haggle to this day. At home my siblings and I helped to extract the caviar, which the three eldest had to take to Hamburg, and process the bladders of the sturgeons, which were used as isinglass for various chemical purposes.

From mid-July onwards, eels began to challenge the sturgeons for dominance. During this period, up to about the end of September, my father received large consignments of eels from Jutland, sometimes as much as 10,000 pounds a week, packed in sacks. Of course we had to be there to clean and process these fish. Anything that we didn’t dispatch fresh immediately was packed in barrels and later smoked and shipped. Even in autumn and winter we couldn't just sit back and relax. Now it was the turn of the little fish. Herring and sprats had to be pulled onto iron wires - my fingers still tingle when I think back to this wonderful work. The fish had to be taken out of the icy brine in which they were salted and lined up on the equally cold iron wires. Sometimes we got frozen hands, but it was fun for us children, we even worked in competitions, because for every ten wires completed, we received one Hamburg Schilling as wages.

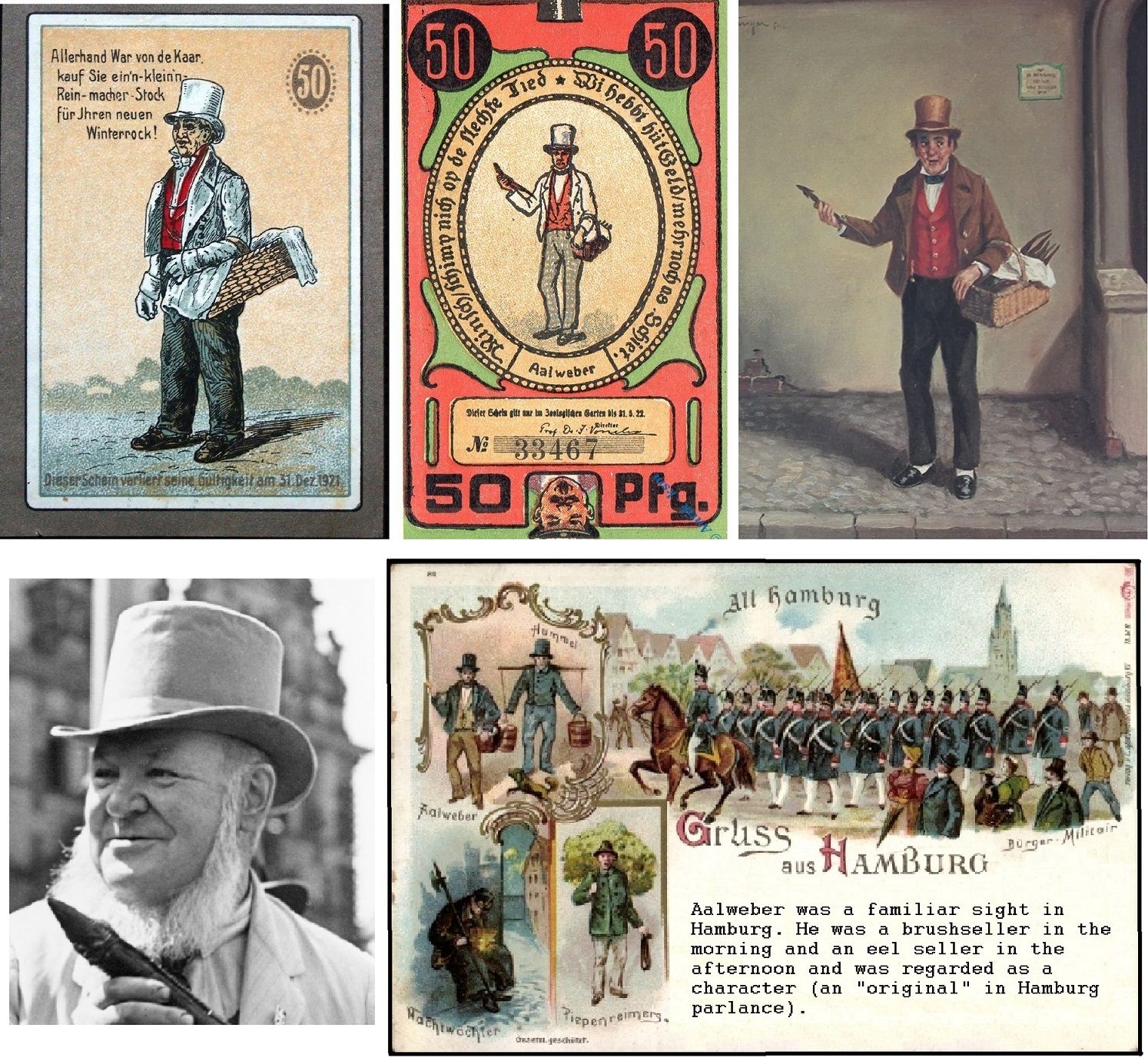

It is impossible for me to recall these episodes from my youth without also remembering two well-known, even famous Hamburg characters, who strangely enough have grown together with our house like the Hamburger Dom. One was old "Aalweber," one of our most loyal customers. I can still envisage him in his light-coloured jacket and red waistcoat, a tall white felt hat on his head, and on his arm a basket of smoked eels covered with a napkin. Who didn't know Aalweber? In the mornings he went about with a cart holding brushes bound with rope, and did this in a very special way. He spoke only in infinitely long verse that never actually broke off. In the afternoon, however, Aalweber roamed the streets with the commodity that earned him his nickname. At that time there was not a single person in Hamburg who did not appear at the Lammermarkt or Waisengrun day, in front of Aalweber's booth in the Kirchenallee in St. Georg, where the "Deutsches Schauspielhaus" is now located, or who did not enjoy Aalweber's eels in some other way. The name of this character is still alive today, not only among the old but also among younger Hamburgers who have never seen him. Probably never has any street vendor enjoyed greater favour and popularity. In a theatre in Steinstrasse they even depicted Aalweber, aptly played by a young actor, onto the stage and the play - called "Gustav or the Masked Ball" - had an enormous following.

(*Aalweber: Johann Jürgen Weber or Karl Weber, 1780 - 1855 , a Hamburg brush binder and eel seller known for his sales pitch e.g. „Aal, rökert Aal! // Madam, kumm gau herdal, // De Köksch de sitt in Kellerlock // Und flickt ehrn Krenolinenrock." )

The other character, who was by no means less famous than Aalweber, was Dannenberg. It is hard to describe this very strange person, although I got to know him better than many people did when I was a boy. Dannenberg lived on the second floor of our building on Petersenstrasse, and of course I always had free admission to his place. This famous man was not handsome because his face, framed by black whiskers, was disfigured by a sunken nose. He wore small rings in his ears, as you can still see on sailors today. But this ugly exterior contrasted with an all the more decent interior and Dannenberg showed incredible industriousness. There was no work that this man, an actor by trade, would not tackle - for money and good words it should be noted. In the morning he could be seen going through the suburbs as a crier and announcing all sorts of news in a loud voice. Sometimes, when he announced auctions on behalf of the city, he carried a large bell in his hand. He usually began his public speeches with the words: "Hört Lüd!" [Hear ye] or "Hear, you Hamburgers and residents!" and then it went something like this:

„Door is hut morgen groote Afschoon of der lange Reeg bi Herrn Mittelstraß öber diverse Mobilien, Kleidungsstücken Gold- un Sülbergeschirr, Koppergerät und sonstige wertvolle Gegenstänn. Wer da Lust to köpen hätt, dee koom stock tein, bring öber Geld mit!"* [Dialect]

(* "Listen, folks, this morning there is a big auction on the Langenreihe at Mr. M.'s for . . . . if you want to buy, come at the stroke of ten o'clock, bring money with you.")

When a child or a dog got lost, when fresh victuals arrived somewhere, Dannenberg announced everything. If there was nothing to announce, then you could see the industrious man chopping wood, helping move things and doing all sorts of other things. Dannenberg had a special temporary job with my father. Of course he had to play the crier here as well, and all St. Paulians will certainly still remember his great praise: "Hear Lüd! Freshly roasted warm Neesen! Bi Hogenbeck in de Peterstroot gives eight big, fat, warm Neesen for one shilling." At other times this man had to look after us three eldest children for everything.

However, Dannenberg's moment of glory only began in the afternoon, for now the crier and unskilled worker was transformed into the theatre director, whose questionable fame has even found its way into the annals of Hamburg theatre history. When Dannenberg stood in front of his Elysium Theatre in St. Pauli, disguised as an ancient knight, in shining armour, helmet on his head and a mighty sword at his side, his sunken nose covered with red make-up, he was unrecognizable. One only recognised him as the St. Paulian town crier when he opened his mouth and invited the audience, this time in elegant High German and raising his voice ever more menacingly, to attend the great tragedy. "Entrance first pew four, second pew two, and last pew, I'm almost ashamed to say it, just one shilling." In the midst of the most pompous chivalrous scenes, rotten apples and eggs sometimes rained down from Mount Olympus onto the stage, and then, while the performance was interrupted, one of the actors had to hurry to the gallery to throw the culprits out into the open. So that was Dannenberg. Those who are more interested in his personality and his theatre will find a good characterization and the most cheerful episodes in Borcherdt's work "Funny Old Hamburg".

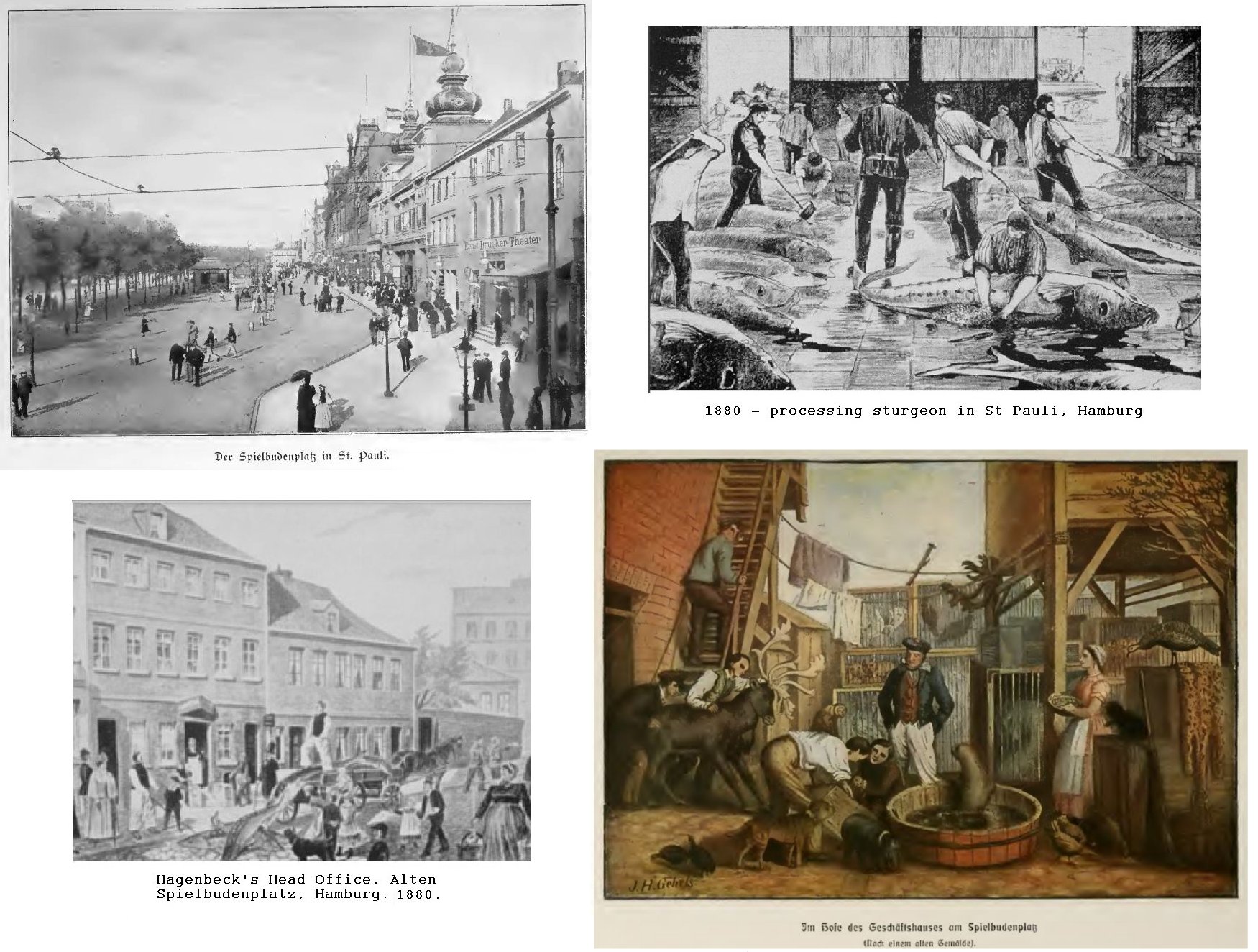

The beginning of the transformation of the fishmonger shop, which was just a food shop, into a pet shop took place during the stormy year of 1848. At the beginning of March, the fishermen, who had set out very early that year to catch sturgeon, caught six seals in their nets. Since the fishermen were contractually obliged to deliver their entire catch to my father, they naturally brought these seals to him as well. Regarding what followed, all one can really say is "small causes, big impacts." My father came up with the happy idea of exhibiting the animals for an entry fee, and for this purpose he exhibited them in two large wooden vats on the Spielbudenplatz in St. Pauli for an entry fee of one schilling (eight pfennigs). Quite good business was done with this display. This was my father's first venture of this kind, as he didn’t trade in pets at that time, and it's fair to say that the whole pet business grew out of this. A berlin business friend suggested to my father that he exhibit the seals in Berlin as well - for modern people it seems a strange idea to take seals to the capital of the Reich to be exhibited as a great rarity. They really were a rarity back then, so the seals were placed in Kroll's garden as quickly as possible. Despite the political turmoil, business wasn't bad at all, but as the revolutionary movement grew daily, my father began to feel uncomfortable in Berlin, so he sold the famous six seals to a Berlin entrepreneur, unfortunately not for cash but on credit, and travelled back to Hamburg. Unfortunately, this entrepreneur had a very bad memory as he went off with the seals and forgot to pay the bill. That was the beginning of the pet trade. It wasn't as bad as it might appear, because my father did not lose anything, and he still had a little money left over from exhibiting the seals in Hamburg and Berlin.

You shouldn’t believe that profit alone played a role in the shows and animal purchases that followed. I can say with a clear conscience that my father also had an innate love for animals,. An animal shop, whether large or small, is unthinkable without a passion for the animal kingdom. My father was a particularly avid animal lover, which was evident from the fact that he always kept goats, a cow, a monkey, a talking parrot, chickens, geese and all sorts of other domestic animals. A pair of peacocks also strutted about in the large rooms used to store the wood chips for smoking fish. So the menagerie already existed before anyone even thought of an animal business.

I must have inherited my father's love of the animal world as my inclination towards animals was expressed quite dramatically in my earliest youth. One day, when I was just two years old, I brought eight live young rats into the house in my apron, to the dismay of my good mother. They were immediately taken from me of course. The result was a horrible screaming that only stopped when my father had the happy idea of giving me a pair of young guinea pigs to play with instead of the missing rats, as he also kept a whole stock of these creatures for his special pleasure. A little later I was given a live mole. A large barrel of sand was prepared as a residence for the new inhabitant. But the main question here was the stomach question. Every evening I made a pilgrimage to the Heiligengeistfeld [Holy Ghost Field, site of the Hamburger Dom] with my eldest siblings to look for earthworms, and this way we kept the mole alive for over two months. He probably would have lived longer if he hadn't died in an accident. During a heavy downpour we forgot to cover the barrel and the poor fellow drowned in his own residence. This was the first little lesson I received regarding the treatment of animals. The accident touched my childhood heart very deeply and, even if unconsciously, I probably learned from the lesson of being more careful.

A few years later, a far stranger mishap happened to me. I was already a twelve-year-old boy and, as a result of my almost self-employed work in the animal business, which was already flourishing more and more, I was completely in control of my own actions and omissions. On our large farm we had half a dozen ducks whose plumage had become very dirty. Since the animals lacked bathing facilities, I came up the idea of providing them with one. I pumped an empty seal tub half full of water, grabbed my ducks and put them in the bath one by one, where they began to cavort merrily. I watched the hustle and bustle with pleasure for a while, then went to our apartment on Petersenstrasse for lunch. I returned after about two and a half hours and was amazed to find no ducks, neither on the water nor in the yard. With the help of a guard, the whole property was searched without success. Then the Keeper said something I found very strange at the time: "Maybe the ducks have drowned." I thought that couldn't be possible at all, but when we examined the pool, we found the six ducks lying still at the bottom. They had indeed drowned. Because of the ingrained dirt, their plumage had not been sufficiently lubricated by the body's natural oils to keep out the water. Their plumage became waterlogged and its weight then pulled the animals down. They should only have been placed in very shallow water at first. Now one can well imagine that my father did not exactly praise me for this deed, but it still taught me a valuable lesson for the future.

The ball started rolling with the seal business. In the next few years, the search for new seals was successful, but my father no longer exhibited them himself, but sold them to traveling showmen. The innocent animals were presented at fairs and markets as "mermaids" or even as "walruses" – the people knew no better. In July 1852, my father was offered an adult polar bear, which Captain Main had brought to Hamburg from Greenland on his ship "Der Junge Gustav". Back then, when only three zoological gardens existed, it was not easy to find a buyer for such a monster. Daring and an enterprising spirit played a part in putting money into a polar bear, so to speak. However, my father did not shy away from doing this and, after much bargaining, he bought the polar bear for 350 Prussian thalers. Coincidentally, at the same time, a striped hyena and some other animals and birds that had arrived by ship also came into his possession, and this whole menagerie was soon being exhibited on Spielbudenplatz in St. Pauli in what was then the Huhnermärder Museum for an entrance fee of four shillings. Now one must not think that one simply put, say, an advertisement in the newspaper and waited for the public to turn up. Oh no! A barker was put in front of the door, and what a barker! The crier Barmbecker, who was very well known at the time, was put into a red dress suit, like the Danish postal officials wore as a uniform, he was given a huge megaphone and with the help of this instrument he had to announce to the astonished crowd that the giant polar bear from Greenland could be viewed for an entrance fee of only four shillings. Such advertising was necessary at that time, because the Spielbudenplatz with the previously mentioned Mattler Theatre and its director Dannenberg, and with its merry-go-rounds and show booths required strong effects. Incidentally, business was doing quite well and encouragingly.

Every year, these shows were followed by performances on the Hamburg Dom, almost all of which, quite apart from the type of advertising, had a comic aftertaste. For example, in the December following the lion's escape from Kreutzberg's menagerie - but I should first say a few words about that. In the autumn of 1858, the lion "Prince", a magnificent, fully grown animal, which was being transported to Harburg, jumped out of a carriage of the aforementioned menagerie. The first thing the escapee did was jump on the neck of the horse pulling the wagon and bite its throat. A cool-headed servant accompanying the wagon, Heinrich Rundshagen, who later became known under the honorary title "Lion of Hamburg", put a noose around the predator's neck and strangled it. Oddly enough, not only was the stuffed lion later shown for money, but Rundshagen, whose heroism had gone to his head, was also shown for money. In the December that followed this earth-shattering event, my father devised a very grand display which, these days, would not attract a cat of course. In the company of old Schuster Baum, another of St. Pauli’s eccentrics, an impression of the lion ride was made and shown in a booth for the entrance fee of a shilling. The artwork consisted of an old stuffed lion skin attached to the neck of an even older stuffed white horse. Both animals came from the Hühnermäder Museum, but their poses were slightly changed. The traces of blood on the neck of the poor white horse were created by dripping sealing wax. This venture turned out to be extraordinarily lucrative, the audience shuddered with horror, and the lion ride was probably the best Christmas deal my father had done on the Dom up to that point.

During another time at the Dom, it was the turn of the popular giant pig. This time it was a large boar of the English Yorkshire breed, which is known to be poorly bristled. This gave one of my father's workers the original idea of showing the animal as a very special curiosity, namely as a naked giant pig. To this end, the boar was shaved, but things did not go as easily as one might imagine, and the pig was miserably maltreated as a result. On the shield above the stall, of course, was a portrait of the good pig, about twice as big as it really was, with the following verse beneath it:

*You’ve often seen big pigs,

But never as big as this,

So come on in, everybody,

Come and compare its size."

One can well imagine that no great wealth was earned from such shows, but they made at least a few hundred marks, which were very welcome to supplement winter expenses.

Very slowly, alongside the fish shop, the pet shop began to develop. Small business ventures were followed by larger ones, and most involved trips I took part in when I was a boy. From then on, half my life played out on the treadmill, so to speak, I always preferred face-to-face negotiations to written ones, and I achieved the best results that way. In short, before anyone knew it, I was already on the train or the steamboat. I don't think this quality has changed in the least since my boyhood.

I made my first business trip to Bremerhaven when I was eleven, accompanied by my father; here a ship-chandler named Garrels had some animals for sale. At that time you still had to make a detour via Hanover to get from Hamburg to Bremen by train; so a trip to Bremerhaven, which we don’t even think about today, meant a real journey back then. The stock of animals consisted of a large raccoon, two American opossums, a few monkeys and parrots, which were bought and brought to Bremen by steamboat, from where they were to make their way to Hamburg on the deck of the "Diligence". So the menagerie was to make the journey at dizzy heights on the roof of the stagecoach, a risk that did not go unpunished. After the stagecoach had rattled through the night, it was discovered in Harburg in the morning that one of the boxes was empty. During the night the raccoon had chewed its way through the wooden bars and, without a word of goodbye, had fled. I will never forget my father's face when he scratched behind his ears and looked forlornly at the empty box. The raccoon was gone, however, and you didn’t dare make any fuss because otherwise a whole stream of lawsuits might have been thrown at you; because if the escapee wasn't killed soon, bad days were in store for farm owners and their poultry. In fact, the raccoon roamed free around the Luneburg Heath for a full two years until this rare game was killed. We found out about this from the newspaper, but of course we kept very quiet and apart from my father, the postilion and myself, no-one ever found out how the raccoon got into the heath.

There was no shortage of similar episodes, which mostly took place at home. In the middle of our sweetest slumber we were once aroused by a night watchman who, pale with terror, told us that a large seal was slipping about near the moat near the Millerntor. My father immediately set off, and of course I, as the foremost assistant in the animal shop, went too. Luck came to our aid. We were able to catch the fugitive just as he was about to slide down the steep embankment that leads to the water of the city moat. It wasn't hard work to entangle the animal in one of our seal nets and return it to our quarters on Spielbudenplatz. However, had the seal got into the water first, catching it would have been much more difficult.

Another time, also in the night, we were surprised by our old warden with the report that a stray hyena, which had been packed up the night before and was to be dispatched the next morning, had escaped. My father was not a little shocked because we had no experience in dealing with such predators at the time. My eldest sister and I were taken along as assistants because the keeper was already an old man, well into his seventies, whose help one couldn't count on, and then we went to the Spielbudenplatz. When we entered the menagerie, my sister with a lamp, my father and I each armed with a sea-net, we carefully searched the room and finally found the hyena hiding in a corner under a large monkey box. According to the nature of her sex, she greeted us with a horrid howl, but dared not attack. With long sticks we finally got the animal out from under the box. Just as it was about to pounce in anger on my father, the latter with great skill threw the seal net over its head, and in a moment the beast was entangled in the mesh. Within a few minutes we brought the captured animal into an empty predator box. But the whole adventure did not happen as quickly as I have related it here, for we did not return to our home until about eight o'clock in the morning.

Another adventure that I remember fondly from that time did not go so smoothly. This time my father had to pass a rencontre with monkeys, namely with baboons. A number of baboons were to be caught out of a large monkey cage by means of a sack-net. My father, standing in the cage, had one specimen in the net and was about to bring it out when, hearing the prisoner's screams, all the other baboons, about a dozen in number, attacked my father and scratched and bit him miserably. He managed to leave the cage, admittedly covered in blood. Besides a multitude of open bites and scratches, his body showed countless bruises where clothes had protected it. After this incident, the monkeys were always caught using a so-called transfer box into which they were lured with fruit.

And these little adventures may be followed by two more bear stories, but I'm getting ahead of myself a bit, because they didn't take place until a few years later, in 1863, on Spielbudenplatz. A certain Herr Klimek, provision manager of the Hamburg America Line, brought five large, trained bears with him from New York. There were two grizzly bears, two cinnamon bears and a North American black bear. All were owned by "Grizzly Adams," then popular in America, an old trapper who had caught and trained them young, and then roamed the United States with them for years. After the trapper's death, the animals were auctioned off and thus became the property of the provision manager. Da andere Käufer sich nicht fanden, kauften wir die Tiere zu einem ziemlich niedrigen Preise. The animals were housed in cages in the courtyard of our establishment. One night one of the grizzly bears, fortunately a blind animal, broke out of his cage and made himself comfortable on its roof. The calamity was announced to us by a shoemaker who lived nearby, who had been awakened by the noise, had seen with horrified eyes that the bear was loose, and brought the news to us with even greater horror and breathless from running so fast, of course we hurriedly got out of the way. Nothing had happened yet, and the bear lay leisurely on its chest. My father had the happy idea of sticking half a piece of brown bread on a feeding fork and using this bait, which the bear followed sniffing, to lure the animal back into its cage.

So this breakout had a happy ending. A few days later, however, I also had my first bear adventure in the same place. I had the task of "packing" a Russian bear for travel, which by the way is a 1 – 1-and-a-half year-old animal. At first, I struggled for hours to lure the animal into its travel cage using a moving box, but Master Furry didn't feel the least inclination to change residence. Time was pressing. If I wanted to get the animal to the railway station in time, I had to take action. I locked the yard, opened the cage bars and threw small pieces of sugar in front of the bear. That helped. My bear came out of his box and ate one lump of sugar after another as he walked on. Just as he bent down again for a piece, I grabbed his neck with one hand and grabbed the deep fur of his back with the other, trying to force the bear into the cage in this way. But I had made a miscalculation, and a real duel ensued. The bear was far stronger than I had imagined. At first it bristled in surprise, but then it turned and managed to grab me with its front paws. In the next moment the most splendid wrestling match was in progress. With its sharp claws, the bear literally ripped my clothes off my body in tatters; the animal bit and scratched furiously, and in an instant it was no longer my clothes but my own precious skin that was involved. I received the first serious wounds. The warden I called for support only took one look at the fighting group and bravely fled to a safe distance instead of rushing to my aid. However, I did not give up. Using all my strength, I threw myself on the angry animal and finally showed him who was master. Then I managed to squeeze it into its cage and get it to the railway in time, despite my somewhat dishevelled condition. The furry brown ruffian had nearly stripped me, had inflicted a severe bite on my right hand and a number of other bites and scratches on other parts of my body, but fortunately the wounds proved harmless. After this episode, however, I never tried to "lure" bears from one cage to another in this way again.

It is not possible to estimate or describe how many large and small "technical difficulties" my incipient animal business had to contend with over the years. Everything we know today about animal transport and animal treatment had to be tried out in practice and paid for with failures and sacrifices. You don't get experience for free either, it is precisely this that you have to pay for most dearly in life. Unfortunately, lack of experience not only resulted in small adventures and accidents, but also formed a stumbling block for the business as a whole that was difficult to overcome. It was so important that in 1858, a year before my confirmation, my father gave up the thought of the pet shop and concentrated on the fish business, which had continued in the meantime, although the animal business had already assumed larger dimensions. In the previous year alone, some really important – for that time - animal deals were undertaken. Thus my father travelled to Vienna as quickly as possible after receiving a written notice from his bird dealer friend in Vienna that the Africa researcher Dr Natterer had arrived with many animals from the Egyptian Sudan. He found five lions, two leopards, three cheetahs, some hyenas, antelopes and gazelles, and a number of monkeys, which he readily bought, and at a comparatively cheap price because there was no competition. After a six-day train journey involving many difficulties, the animals arrived in Hamburg and very soon changed hands. The beasts of prey found afficionados in various menagerie owners, while the antelopes, gazelles and monkeys, as well as a few cheetahs, found a home in the Amsterdam Zoological Garden.

In spite of such dealings, my father found in a general estimate that most of the money he made as a fishmonger brought in was spent in the pet shop, as lack of experience in the treatment of animals meant many perished. Thus the future of the whole pet business was up in the air. With these thoughts in mind, my father asked me one day whether I wanted to choose the pet shop or the fish shop as my future career. He shared his experiences with me in a fatherly manner and advised me to turn to the fish business. But I'm sure he did this with a heavy heart and only to avoid disappointment. Like himself, however, I was already far too involved in the pet shop and loved dealing with our animals, which had become a habit for me, too much to give even the slightest thought of giving it up. Without further ado, I decided to continue the animal business and, since I was my father's favourite, gained his approval, albeit on the condition that he would not have to pay more than 2000 Marks in the event of a possible subsequent loss. So I now had to see for myself, he said, how I could get on and grow the pet trade. In 1857, the same year in which my father started his first large animal business by purchasing Dr Natterer's animal collection, I also made a somewhat unusual but not bad deal. The peculiarity may be credited to my 13-year youthfulness. In the port of Hamburg I bought 280 large beetles packed in three cigarette cases from the cabin boy on a small schooner that had returned from Central America. I made the boy overjoyed with two and a half Hamburg shillings a piece, that's twenty pfennigs according to our money. But when I showed my father this purchase, he was not at all pleased and said, "Well, whatever you earn from those cockroaches, you can keep to yourself." This time, my father was wrong. First I showed the collection to the master baker Dorries, who was a great connoisseur of beetles and butterflies, and he said I should be able to get at least 1-2 marks for each beetle if I sold the collection to the natural history dealer Breitruck. At the time, Breitruck owned the largest shellfish and natural produce business in Germany. In short, I actually sold my three crates of beetles to Breitruck and received no less than 100 thalers. Incidentally, Breitruck did not fare badly in this business, for he passed the whole collection on to the London animal dealer Jamrach for a much higher price.

By the way, when I was 14 years old, I already knew a lot about the actual animal trade, as I had accompanied my father on most trips. So, after I left school in March 1859 at the age of fifteen, things got serious. I devoted myself entirely to the pet trade while my father was only in charge of the fish business. His passion, however, was still the animal business, and his advice remained authoritative. I was never happier than when I had earned my father's praise through a successfully completed business deal. To the end of his life, my father remained the kindest adviser and restless collaborator. And just as he laid the foundation for the material business, he also laid the foundation for activity, perseverance and moderation and planted the love of animals in our hearts, so that all successes of a later time still go back to him, who has long since been slumbering under the turf.

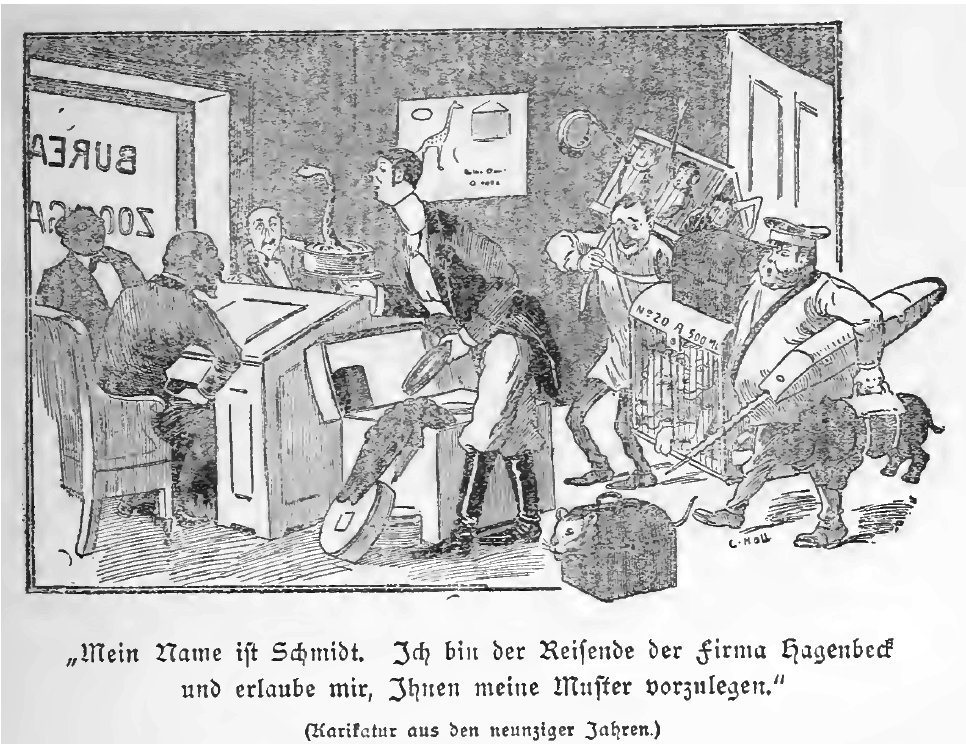

II. DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANIMAL TRADE.

A difficult, but deeply satisfying, time now began for me. Inclination and profession flowed together, and I approached my new business with enthusiasm. Animals had to be bought and sold, the proper housing and treatment of the animals was a constant concern, and there was also the economic side of the business, which caused a lot of headaches. My sister Caroline helped me with bookkeeping and paperwork, while sisters Luise and Christiane took care of the birds. My brother Wilhelm acted as coachman and had to get the living goods in and out of the house. For myself there was an overabundance of work, for it was and always has been our principle that work ennobles man. In caring for the larger animals, I was only assisted by an old keeper. At that time, most of the work was made by the seals, which were housed in large tubs. Fresh water had to be pumped into these tubs early every morning, and for this purpose I had to stand at the pump for two or three hours. When I had finally finished the pumping, I dragged my fish basket over to feed the sick souls one by one.

Newly arrived animals, which were still shy and wild, were simply thrown their food, but after a few days they became so tame that they took food from the hand. Only the older specimens were an exception and could only be made to eat with difficulty. Old seals are difficult to acclimatise to a new environment, and the animals will grieve and sometimes starve for weeks before deciding to eat. Like my father, I had and still have a special affection for seals. I must have told a French interviewer something similar recently, but this gentleman had a rather lively imagination, for he claimed in the newspapers of his native country that I had once gotten a seal so far that it cried out "Papa" whenever it saw me. The truth is that the animals knew me well. When I appeared in the courtyard in the morning and greeted the animals with the call: "Paul, Paul" (all seals were given the name Paul), all stretched their long necks out of the tub. It was always the common North Sea seals (Phoca vitulina) that our fishermen brought us. We once had a grey seal that was very agile and often escaped from its bathtub. It was this animal that once escaped in the night and slid for a walk in the city. At home it had become so tame that it followed me around the yard like a dog, it soon learned to sit up straight, turn around in the pool on command and many other things, for which it was always rewarded with an extra fish.

I got into my first major deal when I was just over 16, and it is interesting to see how chance, which plays a major part in life, came to my aid. You just have to keep your eyes open and try to use every situation appropriately, "to make the best of it", as the English say. At that time, the menagerie owner August Scholz came to Hamburg with a young, five-foot-high elephant, which he lodged with us for one night in order to dispatch it the next day with other animals bought from us. First, Scholz and I led the elephant through the streets to the train station. However, this shipment was interrupted by a small interlude. On Lombardsbrücke the pachyderm became shy and ran away from us. Of course, there was a nice crowd. After chasing through the grounds for more than half an hour, the elephant was finally brought back in, bound by the legs and tied behind the wagon, whereupon he had the sense to be taken to the station. At the railway station, Scholz asked me to accompany him to Berlin at his expense. I was willing to do this and gave our coachman the task of bringing me a blanket at the station and telling my father that I had gone to Berlin as Scholzen's assistant. Next noon the shipment was completed, whereby the animals were transported with an extra locomotive through the middle of the city to another station. Nothing was more natural than that I would use the free afternoon to visit the Zoological Gardens.

I was no stranger to the Zoological Gardens, and I already knew the inspector. When I went to see him and offered him several of our animals, he informed me, to my great delight, that I had probably come at just the right time, as there were various gaps in the predator house that could be filled. A few days later I sold animals to the director, Professor Peters, for almost 1700 talers. I was quite pleased with my success and could hardly get back to Hamburg fast enough to tell to my father.

More important transactions took place in the autumn of 1862, when I took a trip to Antwerp with my father. An animal auction took place every year in the Antwerp Zoological Garden, which was mainly attended by the directors of the few zoological gardens and by animal lovers. The main buyer at that time was the London animal dealer Charles Jamrach, who did his shopping in Antwerp and at the same time did barter deals. It was hard to imagine beating this competitor, who was more powerful than us at the time, but it happened anyway, and in a way that exceeded our wildest expectations. On the trip to Antwerp we visited the Cologne Zoological Garden, which had only existed for a few years, and we concluded some barter and purchase transactions with the director, Dr. Bodinus. Dr. Bodinus had been part of our circle of business friends since 1860. In that year he was in Hamburg and bought a whole range of animals of various kinds, which filled several truckloads. These animals were the first occupants to move into the empty houses of the Cologne Zoological Garden, which then opened in July of the same year.

In Antwerp we made only a few small purchases on the first day. In the evening, when my father was tired, I visited the Zoological Garden on my own, without any particular intention, and was introduced by our friend, Director Schopf from Dresden, to a few gentlemen I don't think I'd met personally before. Among these was the director of the "Jardin d'Acclimatisation" in Paris, Monsieur Geoffroy St. Hilaire, whom I have often met since then and who gave me many valuable tips. In addition, that evening I had the opportunity to meet director Martin from the Zoological Gardens in Rotterdam and director Westermann from Amsterdam, and to conclude quite large purchases and sales with these gentlemen. Geoffroy St. Hilaire had secretly inquired about our circumstances from an animal lover we knew, Count Cornelli, and the information must have been very good, for I made the most important deal in Antwerp with the Paris director. The good Jamrach, who arrived later, was horrified to learn that I had beaten him to it and had left him almost nothing.

By a strange coincidence, a few days later I had to thwart the intentions of the London firm again, and very keenly at that. Of course, this did not cause us any regrets, and I can probably say that my father was very amused when I presented him with the list of transactions I had concluded in the evening and told him how we had beaten our competitor.

As soon as I got back to Hamburg, I found among the correspondence that had arrived there a letter from the widow of the menagerie owner Christian Renz, who was visiting the fair in Krefeld at the time and wished to sell her menagerie. I would have loved to have left again right away. But my father had reservations, he thought it would be too much for us if we also took on these animals over the winter, and between the back and forth of deliberations the letter remained unanswered for a while. Four days later in the afternoon a second letter arrived from the widow Renz, in which she asked for immediate information as she had also offered the animals to Herr Jamrach, who would take them if we didn't get them. Now I got serious and got my father's approval to buy the menagerie. Time was pressing. The Harburg steamer, which connected with the train in question, left in half an hour. I didn't even have time to fetch an overcoat or other travel essentials from our apartment in Petersenstrasse, but hurriedly went and stood at the steamer, which I reached just in time. But I had the most important thing with me, namely 100 thalers in cash, so that I could at least make a down payment for the animals.

I arrived in Krefeld around eleven the next morning and immediately went to the menagerie. Here I found four wagons full of animals, including a very full-maned Barbary lion, more beautiful than I have seen since. Also a white arctic wolf, a jaguar, some panthers and many other animals, all of which I acquired within a few minutes. I paid 50 thalers as a deposit and made the condition that the animals would be brought to Hamburg by the managing director the next day, at the end of the fair. The remainder would be paid then. But only some of the animals were actually shipped, because after Mrs. Renz pointed out to me that she could have sold various animals already to small show booth owners who were at the fair, business immediately got going. I got in touch with these people and in no time I had sold animals from my stock for 700 talers. And now comes a small, sweet interlude. At Oberhausen station, where I had to change trains, my dear Mr. Jamrach from London, whom I had seen in Antwerp only seen a few days ago, suddenly stood opposite me. I couldn't possibly remember him fondly, and he was also somewhat shocked at the sight of me and asked, quite taken aback, where I had "been this time". "In Krefeld," I said dryly, " where I acquired widow Renz’s menagerie." This news caused the gentleman from London quite a bit of excitement, his voice sounded a bit strained and uncertain when he asked me: "What do you want to do with all these creatures so close to winter?" "Let that be my concern," I replied, then casually added, "By the way, a large number of the animals have already been sold on the spot."

The next morning I arrived in Hamburg with a full wallet and was able to stand up to my father with honours. I received a gift of 100 thalers for proving my quickness. My father would not regret this gift, because the deal with widow Renz brought us a profit of more than 2000 thalers. I want to say the following about the fate of the animals. The lions were given to an English business friend, Charles Rice in London, who sold them on to the Fairgraves menagerie, who were traveling in England. It is noteworthy that Fairgraves bred the beautiful Barbary lion with large Cape lionesses and obtained a magnificent breed. When he later retired and dissolved his menagerie, the finest animals found accommodation in the Bristol and Dublin Zoological Gardens. From then on, the most beautiful lions to be found in Europe were bred here. Within a few days I had sold the other Renz animals to various menagerie owners, whom I had already informed before the trip.

Even without special assurances, one can see from such transactions that the animal shop was constantly expanding. In 1863 my father bought the house at Spielbudenplatz No. 19, which was right next to the museum, where we had previously had our business. The front building had two shops downstairs, one rented to a shoemaker, and the other housing our birds. Behind the house was a small courtyard, and behind that a large building, eighty feet long and thirty feet wide, which we arranged to suit our purposes. To the right were placed a number of cages for beasts of prey. The left side was divided into stables for other animals. A small photographic studio was built above the courtyard. Boxes for larger animals were placed in the open space of the courtyard.

The last few years had given me new connections with England, France, Holland and Belgium, and the menagerie at Schaubudenplatz always had a substantial population of animals. In the winter of 1864, I made my first trip to England, which has since been followed by countless others, for I subsequently went to London about twelve to fourteen times a year to buy animals from dealers there. My dependence on the London market only ended later, after the founding of the German Reich and the upswing of German overseas relations. I have memories of many interesting experiences from that time.

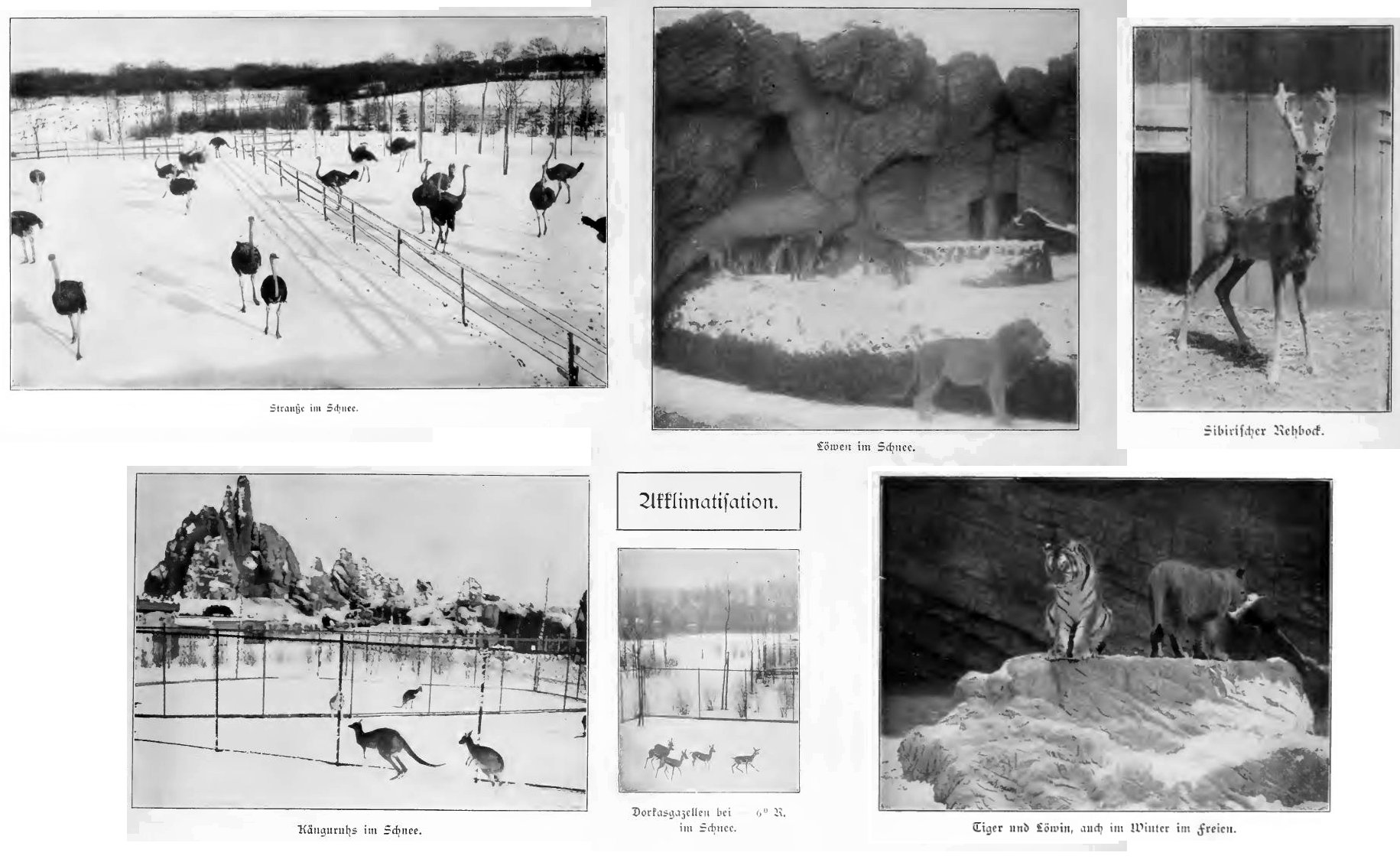

Transporting a giant anteater, which I bought in London in March 1864, turned out to be quite an adventure. I had never seen an animal of this kind, and when news reached me from an English friend in Hamburg that an adult anteater had arrived in Southampton from Argentina, I left immediately for England. The animal's owner lived at a country estate four miles from Southampton, and we travelled there by coach. The anteater roamed free in the garden where the snow lay two inches deep, an observation which, along with others like it, encouraged me to ever more extensive attempts at acclimatization. The animal spent the night in the chicken coop, where a few bundles of hay were piled up and it burrowed into this. After I bought the animal, the previous owner said I could take it with me in the hackney-cab, provided the windows were locked so that it couldn't slip out. Since I had no idea of the danger of such an animal, I allowed myself to be persuaded to take the anteater inside the cab with me, and my friend sat on the box.

So there I was sitting with my four-legged neighbour, who was becoming alarmingly restless and suddenly tried to grab me with his two sharp front claws. At first, he set his sights on my legs, which he clutched so hard that I had trouble releasing him. During the whole trip we scuffled back and forth, I was constantly having to fend off new attacks, which wasn't an easy task, because the animal measured 7-and-a-half feet from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail and was extremely strong. I was completely drained of energy when we finally got to Southampton and I was able to call on my friend for help. The animal was then transported to London in a packing box. The food that the anteater had been given daily consisted of eight raw eggs and a pound of chopped meat, and he was given warm milk as a drink. On the crossing from London to Hamburg we had very stormy weather and I went to bed seasick. Although I could hardly move, I prepared the anteater’s food and asked the ship's carpenter, whom I knew, to feed my animals. There was an amusing incident. The ship's carpenter had scarcely left my cabin when he came back and, pale with terror, told me that a long, thin snake had crawled out of the anteater's throat as he tried to feed him. In spite of my weakness, therefore, I had to go below decks to see this wonder. The snake was, of course, nothing more than the anteater's long tongue, with which it licked up the porridge dropped by the frightened carpenter When I arrived in Hamburg, I sold the rare animal to the Zoological Garden, but under very strange conditions. I received part of the purchase price in cash straight away, but further fixed sums only after each month that the animal would remain alive. One did not dare to buy such an expensive and difficult to treat animal on the spot. By now, however, I had accustomed the anteater to a particularly digestible diet of cornmeal and boiled milk, given morning and night, and four raw eggs and half a pound of meat at midday. The animal thrived on this diet and was admired for years as a great rarity in the Hamburg Zoological Garden.

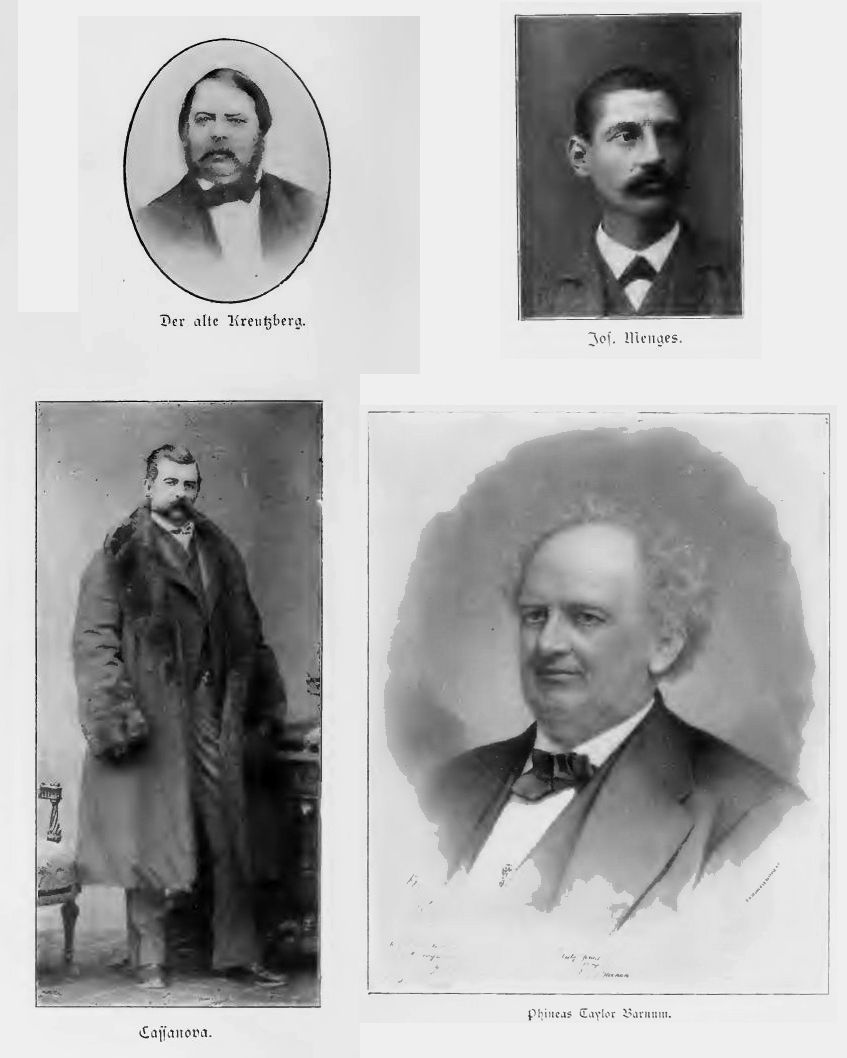

An extraordinarily important connection was made in the same year, 1864. It was late one evening when we received a telegram from Vienna from a friend telling us that Lorenzo Cassanova, a traveller from Africa, had arrived with a shipment of animals that he had collected in Africa, and had travelled to Dresden via Vienna.

Two years earlier, this Cassanova had brought a large shipment of animals from the Egyptian Sudan to Europe, consisting of six giraffes, the first African elephants and many other rare animals. At that time, the traveller had great difficulty selling his animals. We also did not dare to take on such an expensive shipment, so the collection finally passed to the well-known menagerie owner and animal tamer Gottlieb Kreutzberg. This time things were different. In the morning after receiving the telegram I travelled to Dresden and met Cassanova in the Zoological Garden where he kept his animals. This time it was only a small shipment, consisting of two young lions, three striped hyenas, a collection of very beautiful, large monkeys, and a few birds. We agreed very quickly. The main result of this meeting, however, was not so much the purchase of these animals, but the conclusion of a contract, whereby Cassanova would supply us with larger animals such as elephants, giraffes, rhinos, etc. in the future. Since the traveller would not recognize my own signature as fully valid, he travelled with me to Hamburg, where my father signed the contract. All the animals that Cassanova brought home safely from a new trip to Africa would belong to us at a price fixed in the contract, with the sole exception of one elephant, which was intended for the director of the Zoological Gardens in Berlin, Professor Peters.

Cassanova thus began a series of long-distance travellers who searched for wild and rare animals for us in the bush, forest and steppe. In the next year, in July 1865, Cassanova brought his first contractual shipments from Nubia to Vienna. This was mainly three beautiful African elephants, various young lions, a great number of hyenas and leopards, young antelopes, gazelles and ostriches. I was already in Vienna when Cassanova arrived. Here I also met Professor Peters, who had already chosen his elephant. The animals were loaded and first made it safely to Berlin, where they had to be separated from the elephant intended for the garden there. Once again there was a small free performance. With great difficulty we got the animal out of the wagon and lured it a few hundred metres with sugar and bread. Suddenly the two elephants that had stayed behind began to call out something in elephant language to their departing companion, perhaps a farewell. In short, at that moment our elephant turned and ran back to his comrades, dragging us behind him like shuttlecocks. We had no choice but to take the other two elephants out of the wagon and let them accompany the deserter to the zoo. Only after the elephant had been accommodated in its new home could I march back to the station with my two elephants, and then arrive with them in Hamburg without further incident.

As my success grew, so did my courage. Cassanova returned to Africa with larger commissions, and in the following years a whole series of other travellers competed with him. Many factors contributed to making the name Hagenbeck popular at that time. The animal trade as an area of business was new.

The zoos began to flourish and interest in foreign animals suddenly soared. It was difficult to satisfy all the demands that were placed on me. Of course, animals flowed to me not only from Africa, but from all parts of the world, and where I did not travel myself, at least I had my middleman. The trade in Indian animals was then chiefly in the hands of William Jamrach, and I had absolutely no reason to disturb him as a seller, especially as he mainly collected for me, as far as I wished to take his animals from him. Imports from Australia were also still centralized in London and were in contact with me through the aforementioned Mr. Rice. Despite the fact that supplies came from a wide variety of sources and I was almost constantly on the road to get new stock, I was nevertheless often forced to look for missing items from among the duplicates in the Zoological Gardens. Not only Europeans, but also Americans began to rely on us. Even back then, the traveling "shows" in America had taken on dimensions that had never been reached by the menageries and circus ventures in Europe.

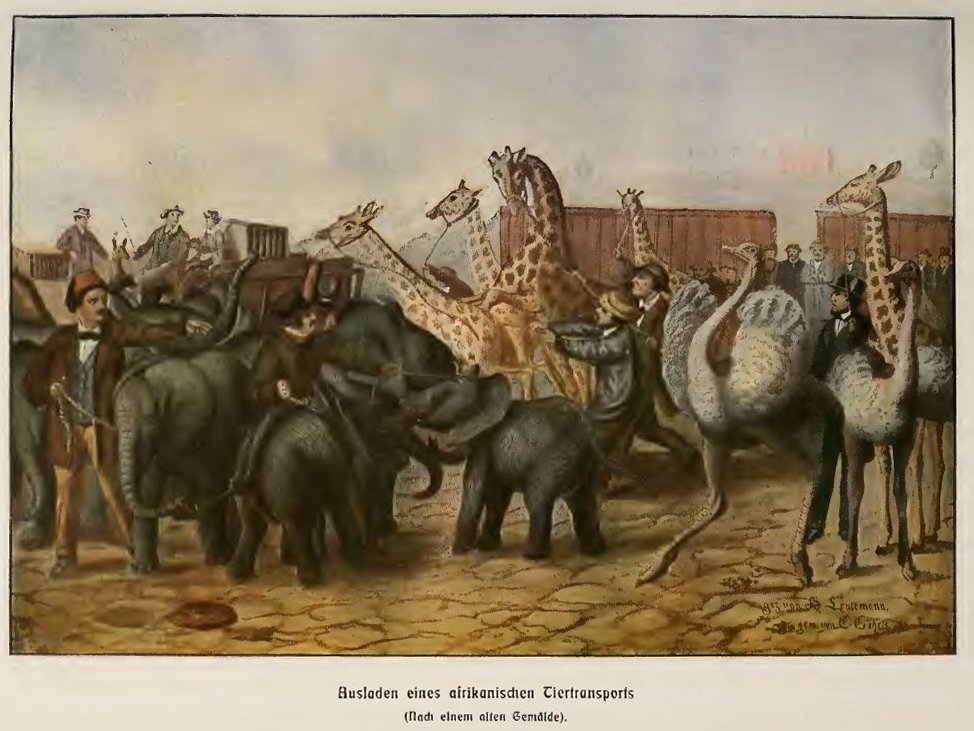

The history of this period is also a history of the development of animal transportation in Europe, because everything in this area had to be learned through experiments. The largest African animal transport I ever received arrived in 1870. Around Whit Monday of that year, news arrived simultaneously from the already familiar Cassanova and from another traveller named Migoletti that both were traveling with large transports of animals from the interior of Africa. Cassanova urged me to leave for Suez at once. There he was seriously ill and was afraid he would never see his family in Vienna again. Migoletti reported that he had met Cassanova and would probably arrive in Suez on the same steamer that had Cassanova's animals on board. There could be no delay. Well provided with an Egyptian letter of credit, I travelled the very next day, accompanied by my youngest brother, via Trieste to Suez, where we safely arrived after a nine-day journey. Even before we had seen Cassanova or Migoletti, we found ourselves among the animals destined for us. At the entrance to Suez station we saw giraffes and elephants in another train, stretching their heads towards us as if in greeting. We found poor Cassanova seriously ill at the Suez Hotel. He had no hope at all, he asked me to pay him credit for his animals, which was fine, and to pass the amount to his wife in Vienna, as he felt that he was at the end of his life. The foreboding feeling of approaching death did not deceive the poor man, he had only a short time left and never saw his family again. But this time we had to leave the sufferer on his sickbed. Necessity compelled us to devote all our energy to the caravan, which, without the man's watchful eye, had fallen into great neglect.

I will never forget the strange scene that presented itself to me when we entered the courtyard of the hotel. If a painter had seen this scene, he might have immortalized it under the title "Captive Wilderness". Elephants and giraffes, antelopes and buffaloes were tied to palm trees. In the background sixteen large ostriches ran about freely, and in 60 crates lions, leopards, cheetahs, 30 spotted hyenas, jackals, lynxes, civet cats, monkeys, marabou storks, rhinos, birds and a large number of birds of prey moved about. After making a list of the entire collection, I concluded a sales contract with Cassanova in the presence of the German consul. After the animals had passed into my possession in this way, not only a real Herculean task awaited us, but also a real struggle on different sides.

Most of Cassanova's people were ill and had paid little attention to the animals, so that, above all, in order to give the poor animals their rights, I first had to take on several Arabs to help. However, we had scarcely begun to give the animals their feed and to prepare their bedding when suddenly a crowd of less than confidence-inspiring Greeks [foreigners] burst into the yard and tumultuously demanded money from me. The leader legitimized himself as one of Cassanova's companions and claimed that he owed him money. He backed up his demand by remarking that if he wasn't satisfied, he would "set the whole thing on fire." Without letting myself be intimidated by the threats, it was immediately clear to me that the only way to calm the outraged feelings was to say "Baksheesh". I guaranteed what Cassanova owed him and at the same time gave the man a tip of 50 francs, whereupon the berserker immediately turned into a lamb who happily complied with my request to help feed the animals. I had given the same tip to the rest of Cassanova's people. As for the other guys that the Greek had brought, I gave 5 francs, and the rabble could hardly leave fast enough to turn the loot into drink. It became clear to me, however, that it was best to get away from Suez as quickly as possible, and once again baksheesh was needed to smooth the way.

Obtaining the necessary wagons for our animals at the railway station was not so easy. The official in question, an Arab, stubbornly maintained that it took at least 6-8 days to assemble that many carriages, that getting it done faster would be like magic and that he was no magician. Strangely enough, after I had also promised this man 50 francs, he actually turned into a magician and assured me with the greatest commitment that all the carriages should be ready the next evening.

In the animal yard, where we called again in the evening, there was a new, unpleasant surprise. The rumour circulated among Cassanova's people that the gang of Greeks that had visited me that morning were planning a real raid on the camp that night. At first I was inclined to take the rumour as ridiculous, but I decided to have six policemen guard the camp. In fact, at about 1 o'clock that night, twenty thugs sneaked up, led by the same fellow who had received 50 francs from me only a few hours earlier. However, when the gang noticed that we were in a state of readiness against them, they quietly withdrew. As I heard later, the attempted robbery was aimed at some boxes full of carpets and other valuables that were among Cassanova's luggage. The chief of the gang had the nerve to come to my hotel the next morning to collect 100 francs that Cassanova owed him. Of course, since the thing was true, I immediately paid the bandit the money to get rid of him.

The transportation of the great caravan was in many ways similar to those expeditions that go to unexplored lands. The system of Nansen and Peary, who, on their arctic expeditions, used sled dogs which became unfit for pulling as fodder for the other animals, is not unlike the system I employed in this and many other shipments, although it was not about dogs in my case. The biggest concern when transporting animals is always food. This time, in addition to a lot of compressed hay, bread and a variety of vegetable feed for the elephants and other animals, we also took 100 milk goats with us to be able to provide our young giraffes and other babies with milk. Goats that could no longer produce milk were periodically slaughtered along the way to feed the young predators.

The magician had kept his word (so that we should keep our word) and the railway carriages were ready at the desired time. First, a mixed train was to go to Alexandria the next morning. One of the most difficult jobs still lay ahead of us, namely transferring the animals to the train station. It would have been extremely lucky to do this without incident, and we weren't exactly lucky. The elephants, giraffes and predators were already housed, and I breathed a sigh of relief. But one should not praise the day before evening arrives! Only sixteen large, full-grown ostriches were left, which were to be led to the station in such a way that two people would hold a bird by its wings and force it to move. My brother and I joined the first ostrich, the other birds were to be held back for the time being by Cassanova's people. The people obeyed this order, but not so the ostriches! We had scarcely gone a few paces from the yard when the other fifteen ostriches rushed through the yard like a whirlwind, knocking over all the keepers and fleeing towards the desert. When I saw this, I did something I shouldn't have done - but one has to learn life’s lessons the hard way. I thought I could hold our ostrich by myself, so I quickly shouted to my brother to let go of the wing he was holding and rush to help the others. But we had scarcely freed the ostrich’s wing when it kicked me so hard in the chest with its long legs that I fell backwards. Faster than a horse, the escapee followed its comrades while I lay on the ground, gasping for breath and looking at the fugitive in amazement.

Curiously, recapturing the flock of escaped ostriches proceeded in an almost ridiculously simple manner. One of Cassanova's ill people, named Seppel, instinctively found the right method, speculating on a peculiarity which animals and men alike obey, namely, habit. But it seemed to be something amazing. Just as I was getting up, I saw Seppel driving the whole herd of goats out to the courtyard. When I called: "Seppel, what are you doing there?" he answered laconically "I want to bring the ostriches back." On his orders, two Arabs had sat on dromedaries and these, as well as the herd of goats, now followed the ostriches quickly. As the procession approached the fugitives, they craned their necks, flapped their wings as if in joy, and danced in a wide circle around the herd of goats and the dromedaries. A quite ludicrous sight. And as if everything was all right again, the whole caravan set off for the station. The ostriches walked among the goats and dromedaries very calmly, as if held by some invisible force. Without much resistance, the birds allowed themselves to be seized and led into the carriage intended for them. The solution to the puzzle was very simple. For the entire forty-two-day journey from Kassala to Suakin, the ostriches had been transported unchained between the herd of goats and the dromedaries. Seppel, who had been there, knew that and had quite correctly calculated that the ostriches would go back to their usual marching order without hesitation.

But I thanked God when we finally finished loading and, although totally exhausted, were able to eat our breakfast, which the manager of the Suez Hotel and his lovely wife had brought to the station for us. Poor Cassanova had left for Alexandria a little earlier. He had been carried to the station on the "Angareb," his African bed. As he was terribly weak, I could scarcely hope of finding him alive in Alexandria.

I will think about the journey from Suez to Alexandria for the rest of my life. Rarely have my nerves been so severely tested. The day was hot, one of the hottest that I can remember. The journey began when, after a few hours of driving, the front carriage of the freight train caught fire. Luckily there was a canal nearby, so the fire was overcome. There was such a jolt as the locomotive pulled that both of our "gulahs," the earthenware water bottles that we had hung in the wagon, shattered. So with the heat came burning thirst. The only happy memory from this trip was meeting a troop of Bedouins who came up to the train to see our giraffes and ostriches. Through a young Nubian whom I had with me, and who knew both Arabic and French, I tried to buy some of the long flintlock rifles from the Bedouins, but they wouldn’t part with any because they were indispensable for hunting. But this little memory, the image of the wild, brown sons of the desert, is lost in the torrent of troubles that followed. In the middle of the journey, they tried to simply leave us lying around in one station. Since the train driver claimed his engine couldn't pull the long train any further, the carriages were simply uncoupled, and the train drove off to Alexandria without us. In the blackest frame of mind, I went round my wagons. How easily this could lead to disaster and deal me an almost irreparable blow. The animals were crammed so tightly together in their wagons that we couldn't even feed them, since we couldn't reach the individual animals without emptying the wagons. Here it was necessary to pull myself together. I remembered that Cassanova had given me a certificate from the imperial court in Vienna, which had been given to him by the inspector of the Imperial and Royal Menagerie at Schoenbrunn, on the occasion of an assignment, with the instruction to show it if necessary for the purpose of expediting the transport of the animals. Under the document was a large, gilded seal, and it was on this that I placed my hope. When I showed it to the station manager, a French-speaking Arab, it immediately made the desired impression. The clerk telegraphed Cairo for permission to hitch an extra locomotive to our carrages, and scarcely an hour had elapsed before our train was transformed into an extra train.

Everything should have gone smoothly now. But disaster again loomed, this time in the form of a drunken engine driver who sped off with the train at such a speed that all the animals were thrown about. But the worst thing was that the train was in constant danger of catching fire. The engine was heated so carelessly that the chimney spat out a veritable volcano of fiery sparks and glowing pieces of coal, which fell like rain between our giraffes on the straw of the wagon. We were kept constantly busy kicking the resulting fire and calming the animals. In the end, however, we had no choice but to throw out all the straw through the side flaps. Finally, however, this terrible night was over, and we reached Alexandria at 6 o'clock in the morning. You can only imagine what state we were in.

The reader may be interested in hearing the rest of the story of this shipment, which is typical in some respects. In Alexandria, the animals were first unloaded and housed again, ready to resume shipping the next morning. At the same time, there was always concern for the feeding and welfare of the animals. We found accommodation at the farm of the wagon owner Migoletti, brother of the African traveller. Here, Migoletti's caravan, which I now also took possession of, also joined us. The day, which followed a sleepless night, was taken up with the provision of foodstuffs for the animals in my care, and with preparations for the shipment, which was to take place the following morning. Only in the evening did I see my poor friend Cassanova again, in whom the spark of life was only glowing very faintly. The sick man was happy to see me again. He also spoke about the shipment being successfully completed to this point. But when I said goodbye at 11 o'clock, I felt that this was a permanent farewell. Just an hour and a half later, Cassanova has gently passed away in his sleep.