EXCERPTS FROM "AN AFRICAN ADVENTURE" (R J DUNSTABLE) - FELIDS HITHERTO UNKNOWN TO SCIENCE

THE AFRICAN WINGED LION, OR PSEUDOGRYPHON

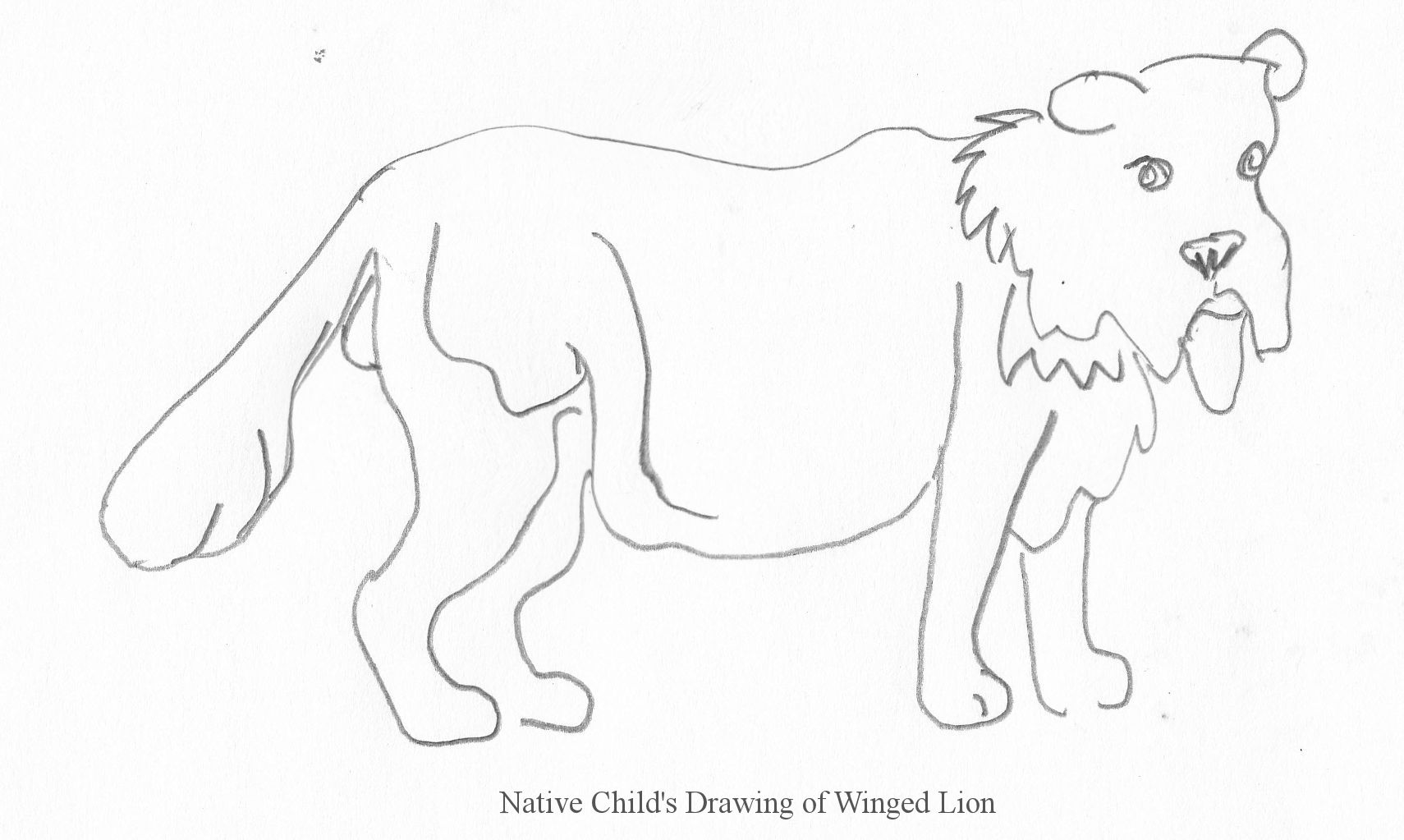

In September, a native man employed in the capacity of handyman reported to me a "lion with wings". As is so often the case in this region, the news reached me through a circuitous route. His brother in a village several miles to the north-west of Mombasa had been given a drawing of the lion, which been made by a child at the missionary school run by a Carmelite sisterhood. He had been instructed by the good sisters to convey the drawing to Doctor Dunstable. One of the sisters, Sister Cecilia, had, additionally, penned a short description of the beast and this was also relayed by the handyman's brother. I take the liberty of reproducing the drawing here.

"14th September. Sir Accompanying this letter is a drawing made by one of my students of an unusual lion, or simba, observed by his uncle. One should not put to much stock on the term "uncle" as, in the extended family of this village, most male relatives outside of the immediate family are termed either "cousin" or "uncle."

This lion is a young male of sandy colour with a scanty mane. He is of an age and size to have been recently been driven from his family and, having no harem of his own, is a lone wanderer. Upon his back by which I mean to either side of his backbone are pendulous wings, being some 12 or 14 inches in width and half as long again. I have made these measurements from the "uncle" who has indicated these measurements through gestures and through the use of a diagram made in the dirt with a stick. These wings are covered in fur identical to that on the sides, being sandy in colour. Sticks and stones were thrown to chase the lion away from penned goats and these wings were observed to rise and fall in the manner of a bird's wings, although the beast remained resolutely earth-bound for all his exertions.

The appendages appeared to cause some distress to the beast by becoming ensnared on thorns and similar obstacles. The villagers believe the exertions of the lion in effecting its escape from such entanglements have cause the further enlargement of the wings by stretching. Further to the unnatural wings, the animals visage is most un-lion-like. Both upper and lower lip are unusually pendulous and, in profile, give the distinct impression of a beak. Due to its combining the aspects of both lion and bird, the villagers call it "eagle-lion" or "bird-lion" which might provide an explanation of the "gryphon" in classical literature.

Some of the villagers view the "eagle-lion" with superstition, claiming it to be a demon that will swoop down upon their goats or, worse, their children. For my part, I have advised these simple, superstitious people, that the animal's condition is no doubt some sort of affliction visited upon it by God in his infinite wisdom and that it poses no greater danger to man nor livestock than any other lion. If anything, it appears enfeebled by its condition; the pendulous wings and lips being more of an encumbrance than a boon."

Upon receipt of the drawing and letter I made arrangements to travel to the handyman's brother's village. The handyman was eager to accompany me and make the appropriate introductions to his family in that village. [details of the journey by bullock cart and introductions to the missionaries and villagers follow]

Victor [one of the "uncles"] and his oldest son, Albert, agreed to guide me to the place where the lion had last been sighted. Upon reaching that location, it was obvious that a dreadful tragedy had taken place. The lion, perhaps encumbered by its peculiar wings or attacked and mortally wounded by an older and more powerful lion, lay upon one side, its flank ripped open and swarming with flies. The beast, though alive, was too far gone to challenge us and did not even lift its head when I put it from its misery with a single bullet into the head,

The beast was already much torn up. A large flap of skin, that might in happier times have given the impression of a wing, had been partly torn from its body although there was a remarkable lack of blood. If anything, it appeared that the wings might be periodically moulted, much like a deer's antlers, and regrown with little distress to the bearer. The upper lip had been partly torn from the face and, like the wing, was fragile and easily damaged.

With the help of Victor, I essayed to skin the lion, but found its whole skin to be unusually fragile. Each knife cut caused the skin to tear, while manipulation of the skin caused the extension of those tears made by its opponents claws in its final battle. Unable to remove the hide intact, I cut away the two wings for examination. Both were badly torn and, when held taut to ascertain their dimensions (in which the good sister was correct), they tore further. Realising that it would prove impossible to preserve these, I dissected the wings and made notes on their construction, which I reproduce here.

The wing on the animal's left side is formed by a flap of elongated skin behind the shoulder blade. It resembles the elongated skin of that "indiarubber" men and women that exhibit themselves are carnivals and circuses. It is 12 inches in width at the point of attachment, tapering to 10 inches. In length it is 17 inches. It can be stretched in both directions and, upon reaching full extension (15 inches width and 24 inches long) it begins to tear. Imagine, if you will, a piece of skin folded back on itself such that both sides are furred. The right wing is much damaged, but laying the pieces together it is observed to be 13 and one half inches wide and 16 inches in length. Neither wing contained bony structures, merely fat and some few strips of meat as though in growing from the animals side some of its meat had stretched into the flap of skin.

Another peculiarity, noticed during this dissection of the creature, was the unusually flat and wide tail. Unlike the normal tapering tail, with which I assume the reader to be familiar from menagerie specimens, the elasticity of the skin was also to be found on this aberrant creature's appendage. When laid flat upon the ground, it appeared to spread laterally on either side of the caudal vertebrae. When held out behind with the slightly "looped" horizontal position, i.e. the normal posture of the tail of a big cat when in motion, the excess of skin depended from the vertebrae much like a curtain or valance depends from a rail. This "curtain" commence 2-3 inches from the junction of tail and hinder parts and stopped 2-3 inches short of the apical tuft. At its greatest depth, and without additional stretching, it was 8 inches and would have presented a serious encumbrance. Due to extreme elasticity of the skin and its fragility, these measurements are the best that could be obtained. It was possible to extend this loose skin even further with minimal force, beyond which it demonstrated a tendency to tear loose.

I would surmise that the Griffon, or Gryphon, of antiquity, most often portrayed as a lion with the head and wings of a giant eagle, was a lion such as this. Certainly from a distance the facial aspect has a comical beak-like appearance while the elongated skin might resemble folded wings when the beast is at rest and, enhancing the illusions, might make a flapping motion when the creature moves at the trot or gallop. In addition to this, the loose skin depending from the tail, hanging as it does from the majority of its length, produces the impression of a birdlike tail. The parallels are too great for this hypothesis of the origin of Gryphon folklore to be discounted.

AFRICAN TIGER

As all educated persons are aware, tigers are not extant in Africa. Whether they were once found in that dark continent remains a matter of debate amongst scholars. Thus when news reached me by telegram that a tiger was roaming the Mau forest region of Kenya I needed no further exhortation to investigate the sighting.

The journey was effected by aeroplane in a fraction of the time of a train journey and with a greater degree of comfort, myself and my companion and our luggage not being jostled. My companion was a Scottish artist, naturalist and doctor of medicine, James Stuart McIntyre, whose fine watercolours of African fauna are reproduced, by his kind permission, in this volume. He has also, with my guidance as to colouration, produced a number of fine colour paintings based on my photographs.

Arriving at the trading post, we settled ourselves in the small hotel there and awaited further news. The indigenous tribe of the region have been employed to capture specimens for European and American zoos. Mindful of the scandal of the Congolese Spotted Lion some 20 years previously, Dr Stevenson and myself wished to obtain images of the alleged African tiger in the field, so to speak, so as to vouch for its origins.

It was more than a week before we received renewed word of the striped lion. Our time since our arrival had not been wasted. I had made a number of fine studies of local people in their labour and of several captives in their pens. My colleague had sketched and painted studies of the captive creatures. We had also used the time to become familiar with the immediate area.

As luck would have it, one of the alleged African tigers had been captured and was being transported to the trading post in a wooden cage. This welcome news was conveyed by a runner who arrived two days in advance of the slower moving animal train. The animals, including a peculiarly striped "Forest Giraffe" (whose flesh is claimed to make good eating) and a blue-eyed albino zebra with sepia-gold stripes as well as the usual assortment of African antelopes, including one the size of a Collie dog, provoked much interest upon their arrival.

Of these I shall only describe those unfamiliar to naturalists [ .] The lioness, or perhaps I should term her a tigress, had the camel or sackcloth colour of a familiar African lion, This colour became a lighter cream on her belly, inside her limbs, on the underside of her tail and on her chin and throat. The contrast was not as pronounced as that seen in the Royal Tiger of Bengal. Her markings, which were a ale chestnut colour that contrasted poorly with the ground colour, were a peculiar mix of stripes and spots, with the spots forming elongated and blurred rosettes that formed discontinuous stripes on her sides. Forward of her shoulders, these gave the impression of spots rather than stripes and her face and lower legs were distinctly spotted while the furthermost portion of the tail was ringed; the rings becoming darker and wider towards the tip. The tail tip, which in a tiger is white, was sandy in this creature. The ocelli, or eye-markings- found on the tiger's ears, and which are white in that species, were sandy in this specimen.

The consideration that she might be a marozi a spotted lion or a hybrid of lion and leopard was dismissed due to the appearance of her markings. These, as I have written, formed discontinuous lines, whereas those of the marozi resemble the markings of the beast presented in the London Zoological gardens as the Congolese Spotted Lion. Unlike that hybrid, which was limber and was likened to a slender lioness, the African Tigress was thicker of limb than a lioness. Her face was, if anything, wider across the forehead and shorter in the nose than most lionesses, in profile resembling a tiger, although the presence of tiger-like markings may have contributed to an optical illusion in this respect. In height to the shoulder, and in length from nose to tail, she was as far as I could tell comparable to a large lioness.

More than anything else, her appearance brought to mind that of a number of lion-tiger mules bred by travelling menageries and described by Lydekker and later photographed by the great showman Carl Hagenbeck in Germany. This aroused suspicions in me that an unscrupulous trader had brought with him either a lion-tiger mule which he wished to pass off as an African Tiger, or was the progeny of a Royal Tiger from India which he had permitted to mate with a native lioness. Her behaviour was in no way tame which weighed my opinion towards the latter.

[ ]I cannot, with any certainty, say that African Tigers exist as the beast I was shown was, without any shadow of a doubt, a hybrid of lion and tiger.

[Dunstable also described in detail the Forest Giraffe (okapi), the sepia-striped zebra, which he identified as an albino "sport" of the familiar plains zebra and the collie-size Dik-Dik antelope]

==

MALTESE OR BLUE LION

Having tracked the pride from the water hole, Joseph, my native guide, gestured that we should halt several yards from the thicket of thorn bushes. It would take a great deal of patient stalking to venture close enough to determine whether this pride included the two "ghost lions" reported by tribesmen in this region. A few moments later, Joseph returned and mouthed the words "ghost lion." Joseph confirmed that the pride tracked thus far comprised seven individuals headed by two males and with bébé (cubs) present, that latter of which he had already concluded from the several sets of pugmarks.

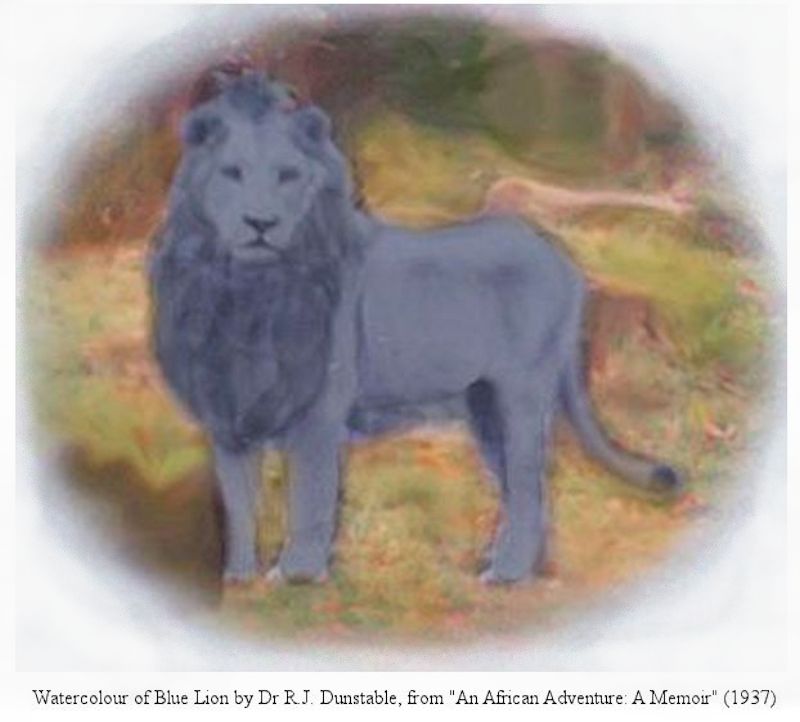

The pride was headed by the two maltese lions, about which many tales were told; that they were spirit lions or demons; that they were the animal forms of white shamans, by which they meant either Europeans or shamans of a rumoured tribe of albino negroes. At this juncture, a description of maltese lions is necessary. These magnificent creatures had medium grey manes and tail tips, shading to charcoal; the shorter pelt of the bodies being of a good maltese blue, as can be seen in cats of the Persian and Russian races. The manes were dense and heavy and gave the impression of many hues of grey, which I believe to be due to the tips of the hairs being considerably darker than the shaft, thus giving a shifting pattern as the creature moved.

Upon the legs, especially the inner sides, the grey was paler and ghostly markings were discernible, these being the cub-markings that never completely fade on any lion and which may always be seen in certain lighting conditions. Many naturalists consider the normal lion to be a solid tawny hue, but this speaks only of a lack of detailed study of living specimens, for the juvenile rosettes remain visible on the limbs well into adulthood and often for the animal's entire lifetime.

The dark markings around their eyes and lips were charcoal rather than black. The nose was a lilac colour with a margin of charcoal. Their eyes were of the normal amber hue, though I felt them to have a slight greenish cast compared to the clear amber of a tawny lion, however, it is not possible to say this with any degree of certainty.

In addition to the two maltese lions, which I supposed to be an alliance of full brothers, the pride comprised five females which were tawny, albeit of a hue washed out in intensity and possessing a somewhat ashy cast. Of the five cubs then present, three were of the maltese variety with darker grey markings while the remaining pair were sandy with golden rosettes.

I had fully intended to take the adult lions as trophies and send one of the skins to the Royal Zoological Society for its collection or for display in the British Museum, where it would make a fine addition to the natural history collection, however, our position was such that it was not safe to take down one of the males without great risk to ourselves. I signalled to Joseph to retreat, intending to track this pride and take my trophies when a better opportunity presented itself. Were it possible to capture the three maltese cubs, these would have made attractive live exhibits at the Zoological Gardens in London.

[ ]Alas, no better opportunity to acquire either the full grown males or the cubs presented itself and I left the region without taking a ghost lion. I left detailed information with Mr R.G. Brooke and his party as to the region frequented by the ghost lions, but their efforts did not meet with success and I fear the strain has been lost, with the maltese lions having been killed by rival males and the cubs destroyed, as is the victor's custom, in order to make the females receptive to the new rulers' advances.

Some years later I spoke with a tribal leader who wore a grey pelt and this resolved the fate of one of the ghost lions. The man had earned great kudos by killing an evil spirit that frequently took the form of a lion the colour of ashes. He allowed me to examine the skin, which had the attributes of an adult male maltese lion, but refused to part with the trophy. It had, in any event, been poorly preserved and much torn by spears.

When I enquired as other members of this lion's pride, the man told me that there had only been one such lion and that it had been a wanderer given to attacking livestock and closely approaching the native villages. From this it seems likely that the maltese brothers had indeed been deposed. One male, no doubt greatly injured from its trial, had been reduced to taking livestock and fallen to the spears of local hunters. His brother, without a doubt, had been killed or mortally wounded. Their maltese offspring had doubtless been destroyed by lions of the more common tawny race, not out of animosity for the cubs, but to hasten their mothers into breeding condition.

It is worth noting that the existence of the maltese lions has a comparable situation in India where a maltese race of the Royal Bengal tiger exists alongside the normal orange race. The two kinds are said to breed with each other, but while an orange tigress may, if native word is to be believed, be found with grey cubs, never yet has a grey tigress been seen with orange cubs. In general, the blue form appears to be found in deeper forest where its darker colouration perhaps affords it better camouflage, while the orange form may be found in heavy brush or in mixed forest. It is no great surprise that both of these noble big cats, the African lion and the Indian tiger, have both tawny and grey races. A further parallel may be found with the situation of the Indian leopard, which has both spotted and black sub-races, although its African cousin appears to lack a black sub-race, and again with the ferocious South American leopard, or jaguar, which again has both spotted and black forms. As to why the lion and the tiger should both have blue, rather than black, races, is a question that may perhaps be answered on provision of either specimens or skins to the Royal Zoological Society.