BLACK'S GUIDE TO GLASGOW AND THE CLYDE

Edited by G. E. MITTON

With five full-page illustrations and seven maps and plans.

LONDON.

Adam and Charles Black

1907

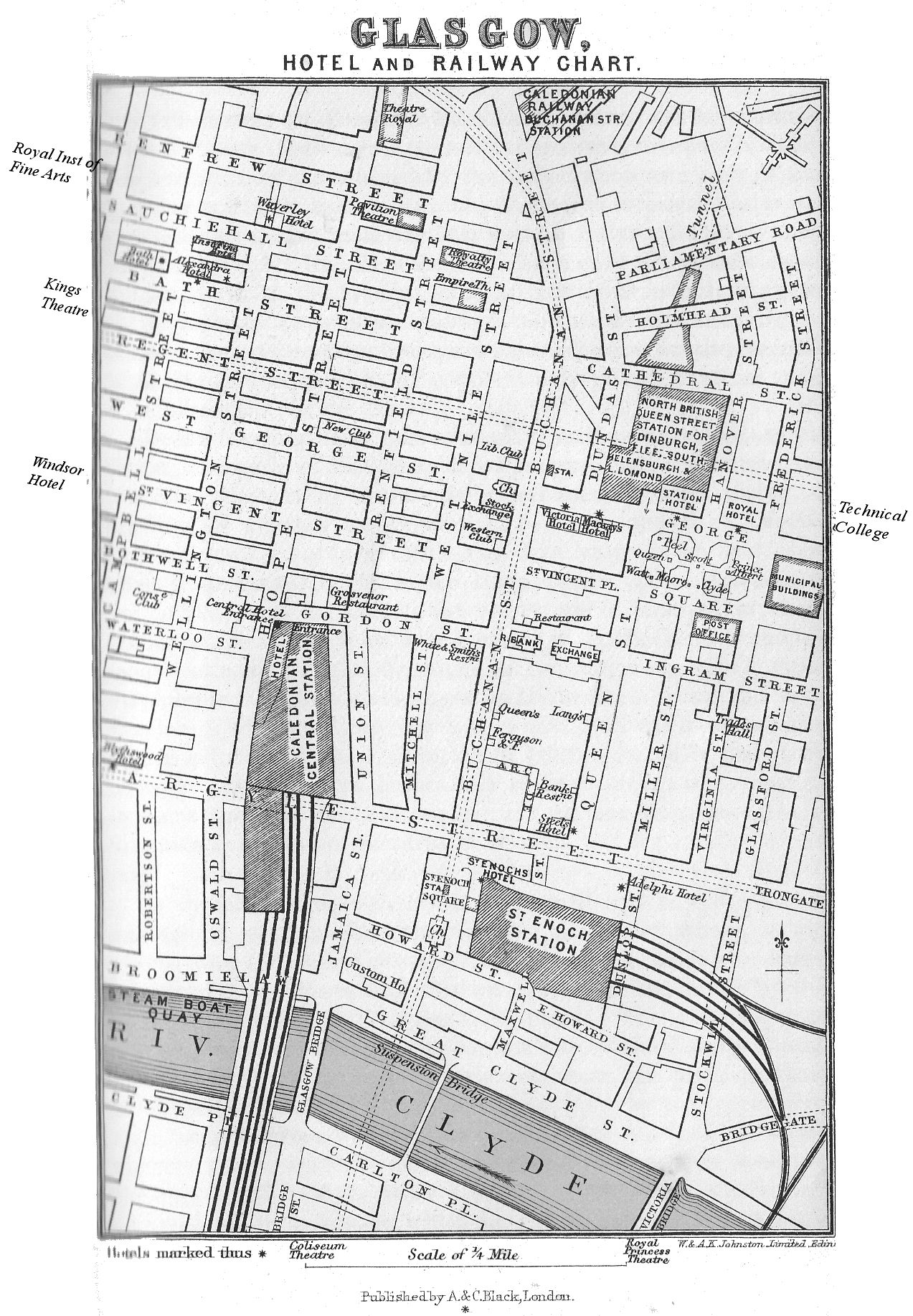

MAPS AND PLANS

Glasgow, Railway Chart

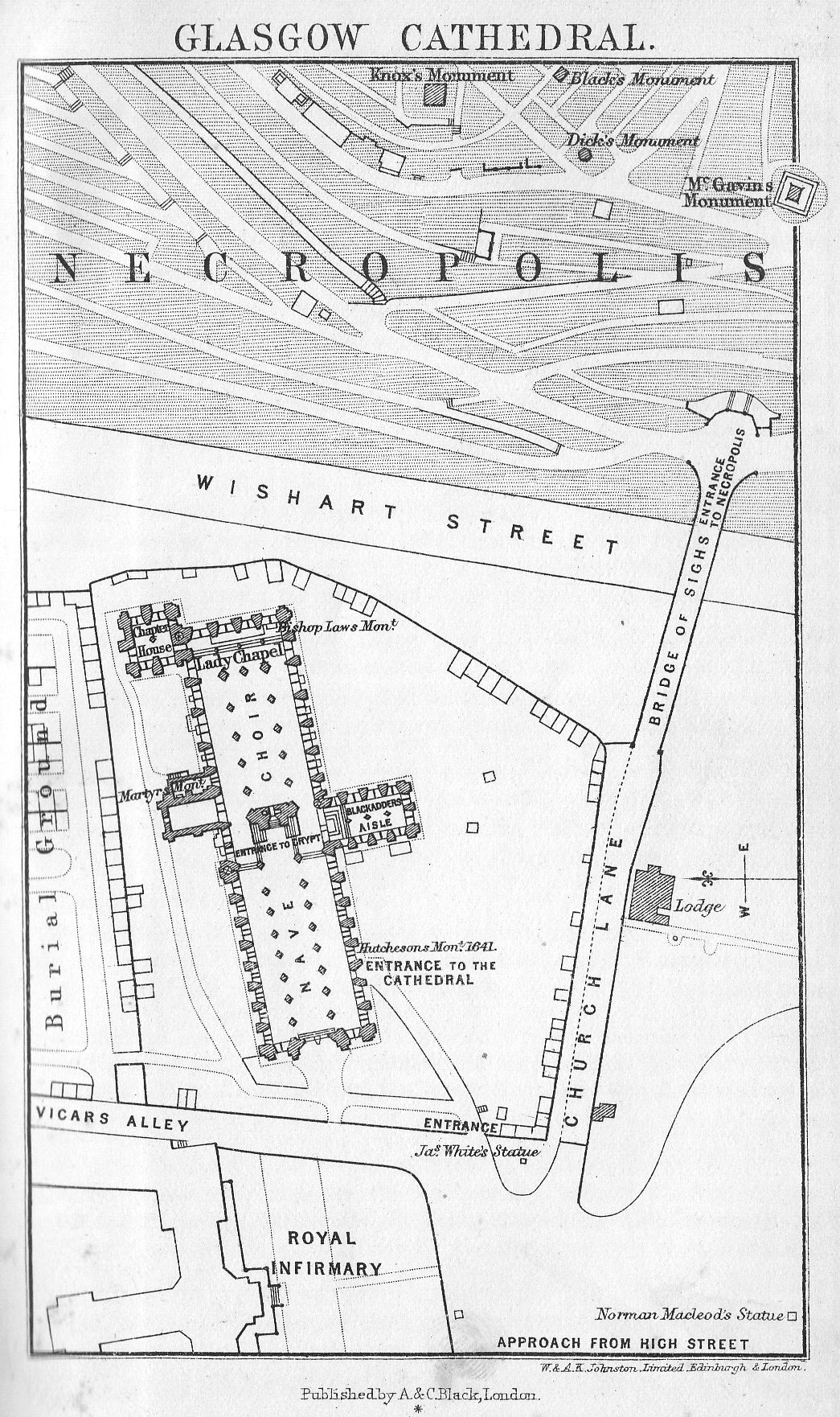

Glasgow, Cathedral, Plan of

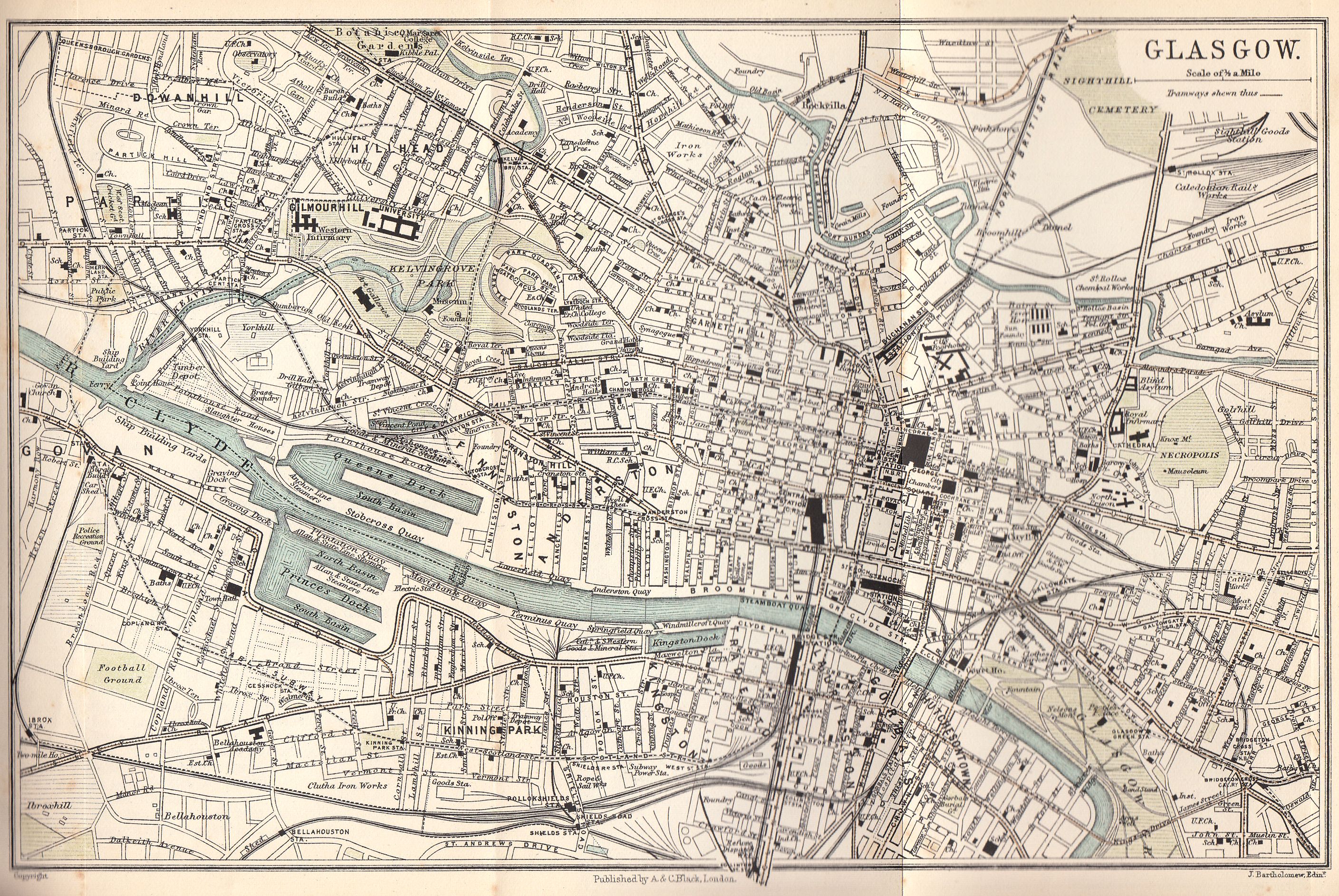

Glasgow, Plan of

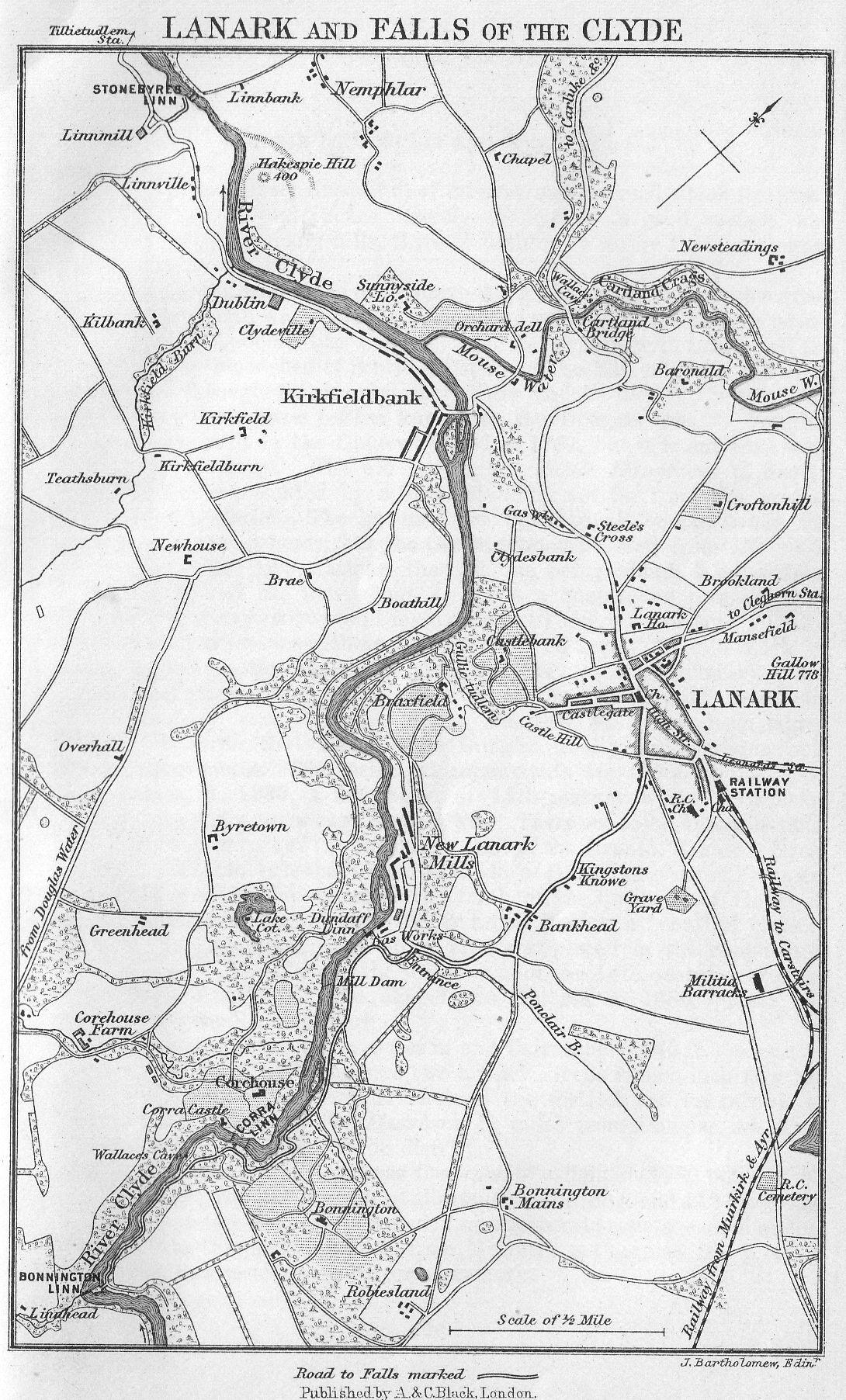

Lanark and the Falls of Clyde

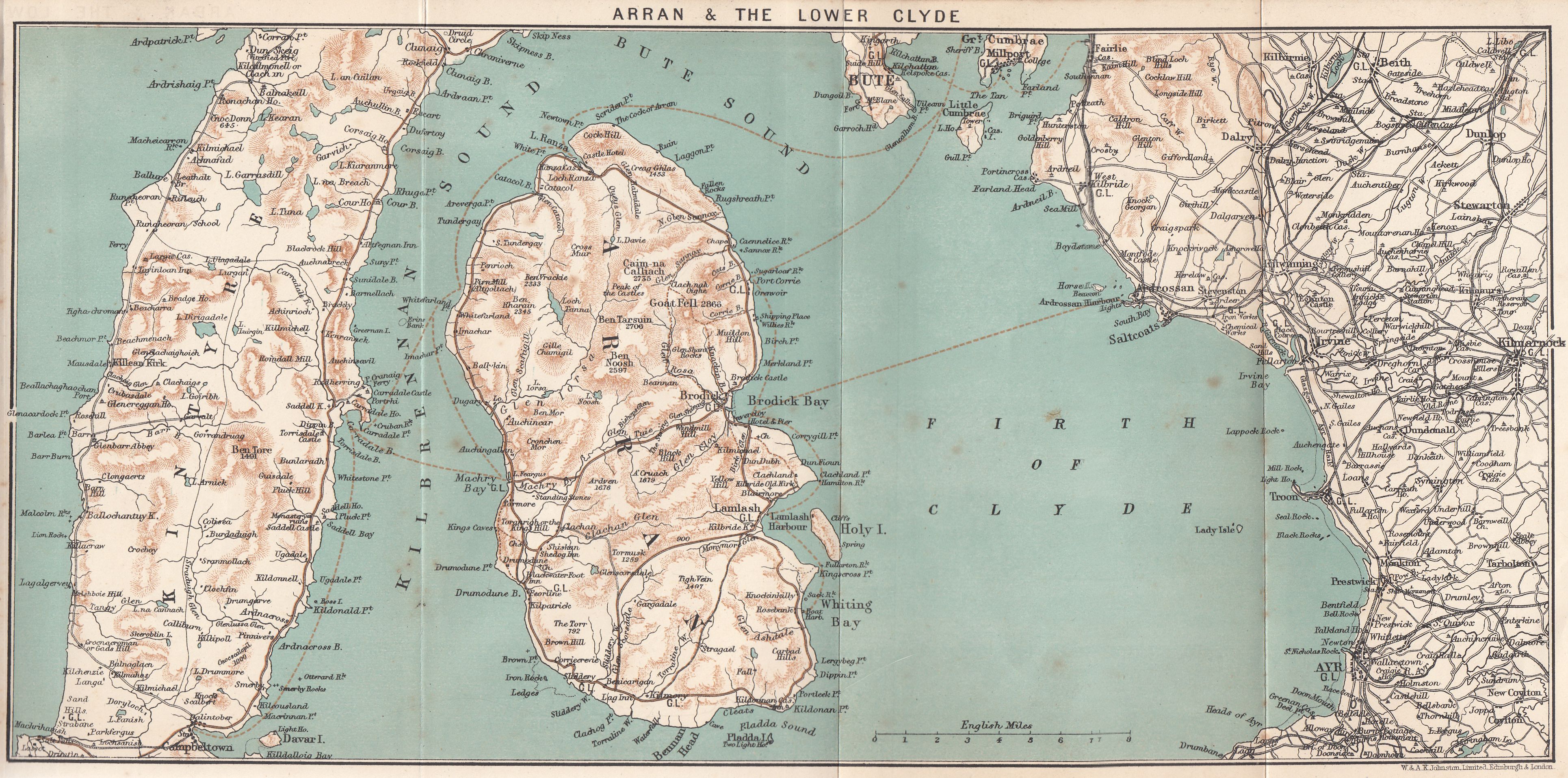

Arran and the Lower Clyde

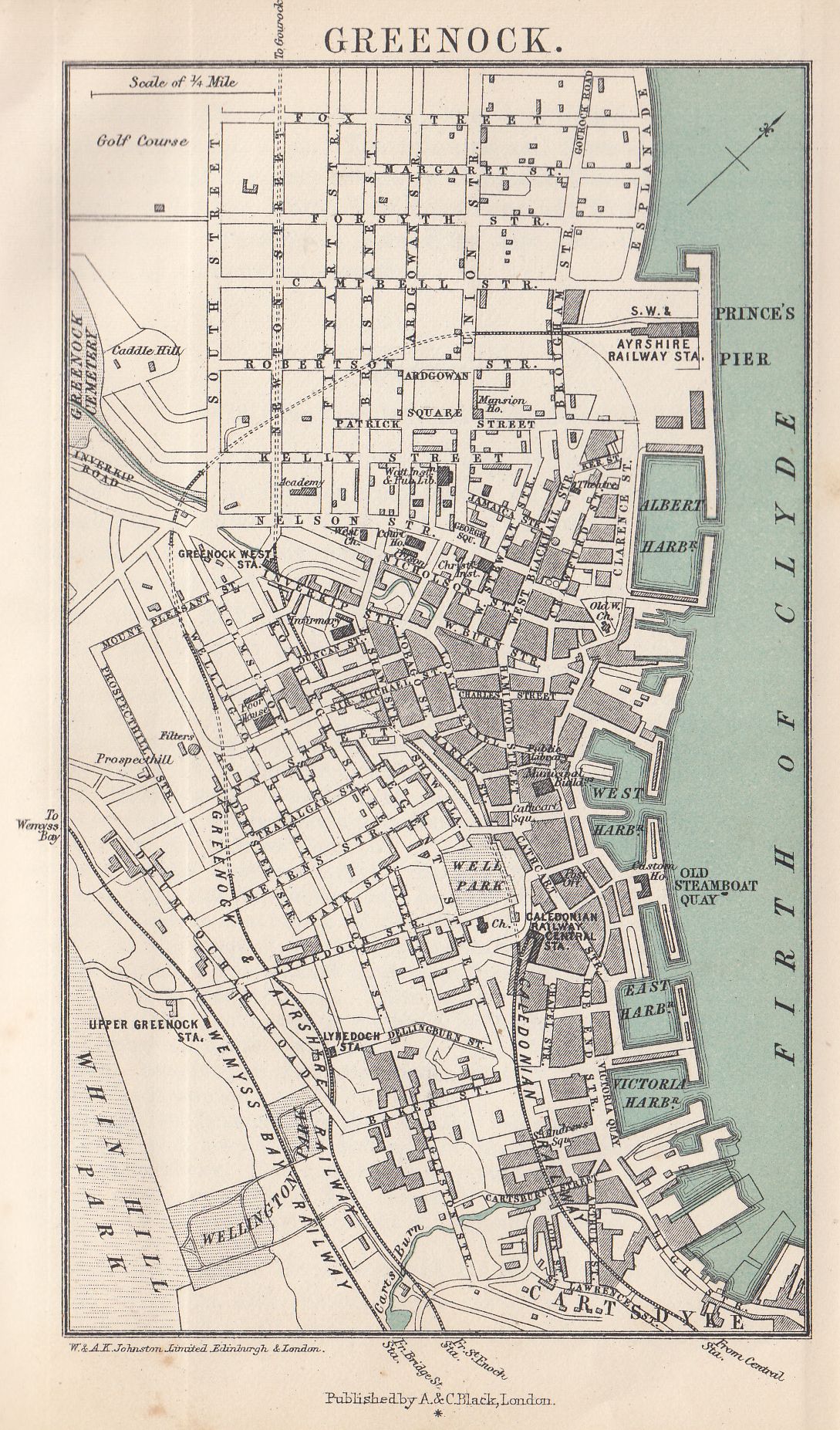

Greenock, Plan of

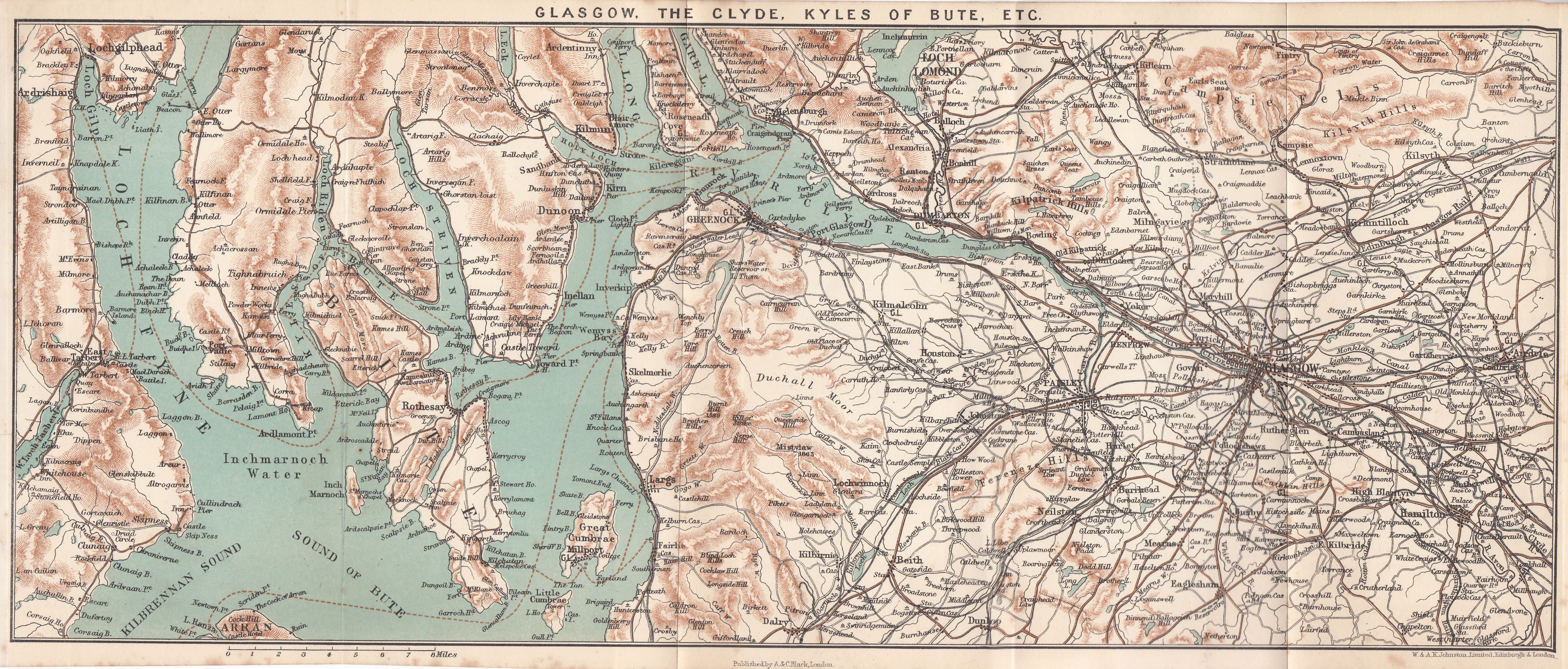

Glasgow, the Clyde, Kyles of Bute, etc.

ILLUSTRATIONS

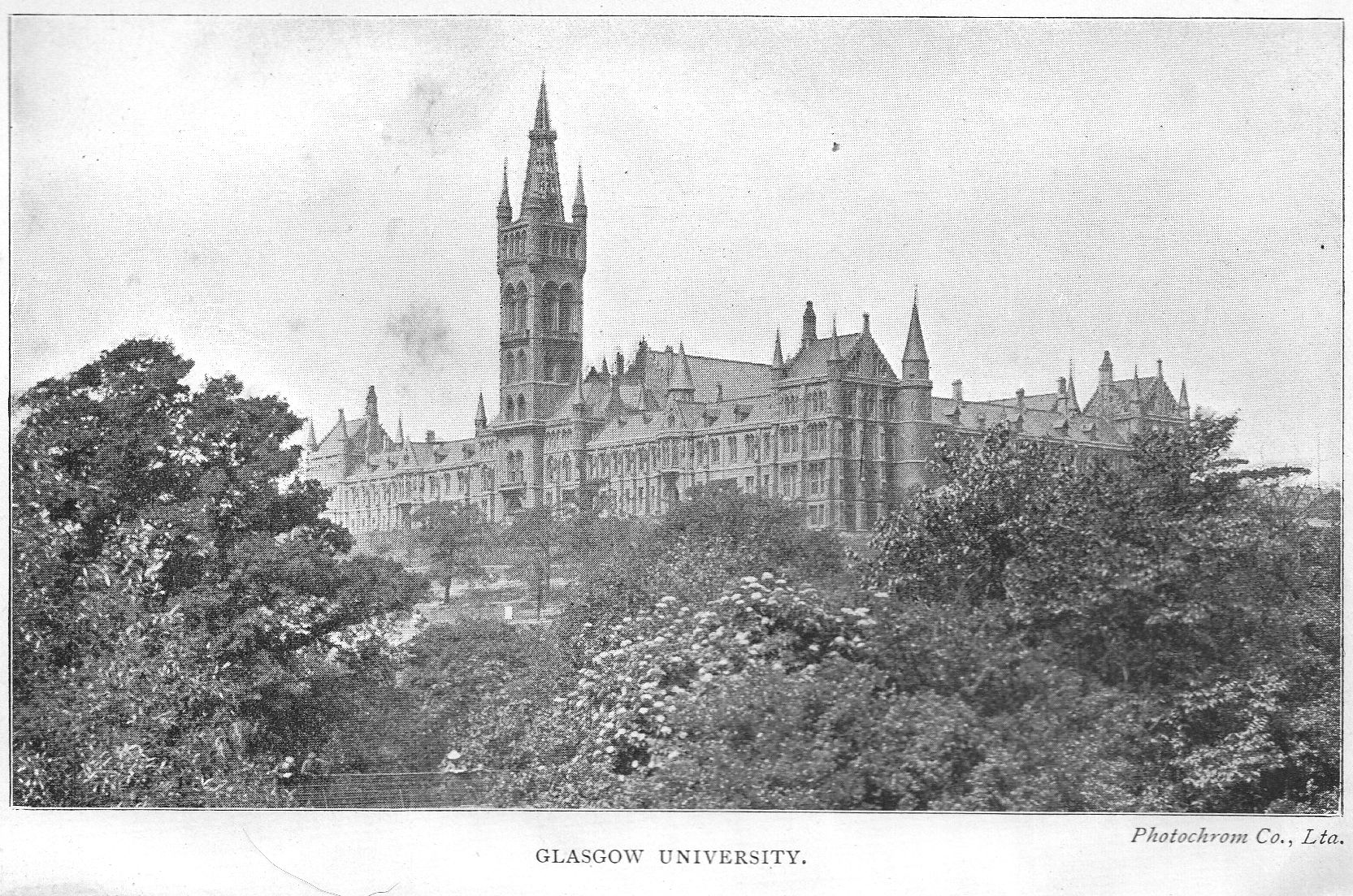

Glasgow University

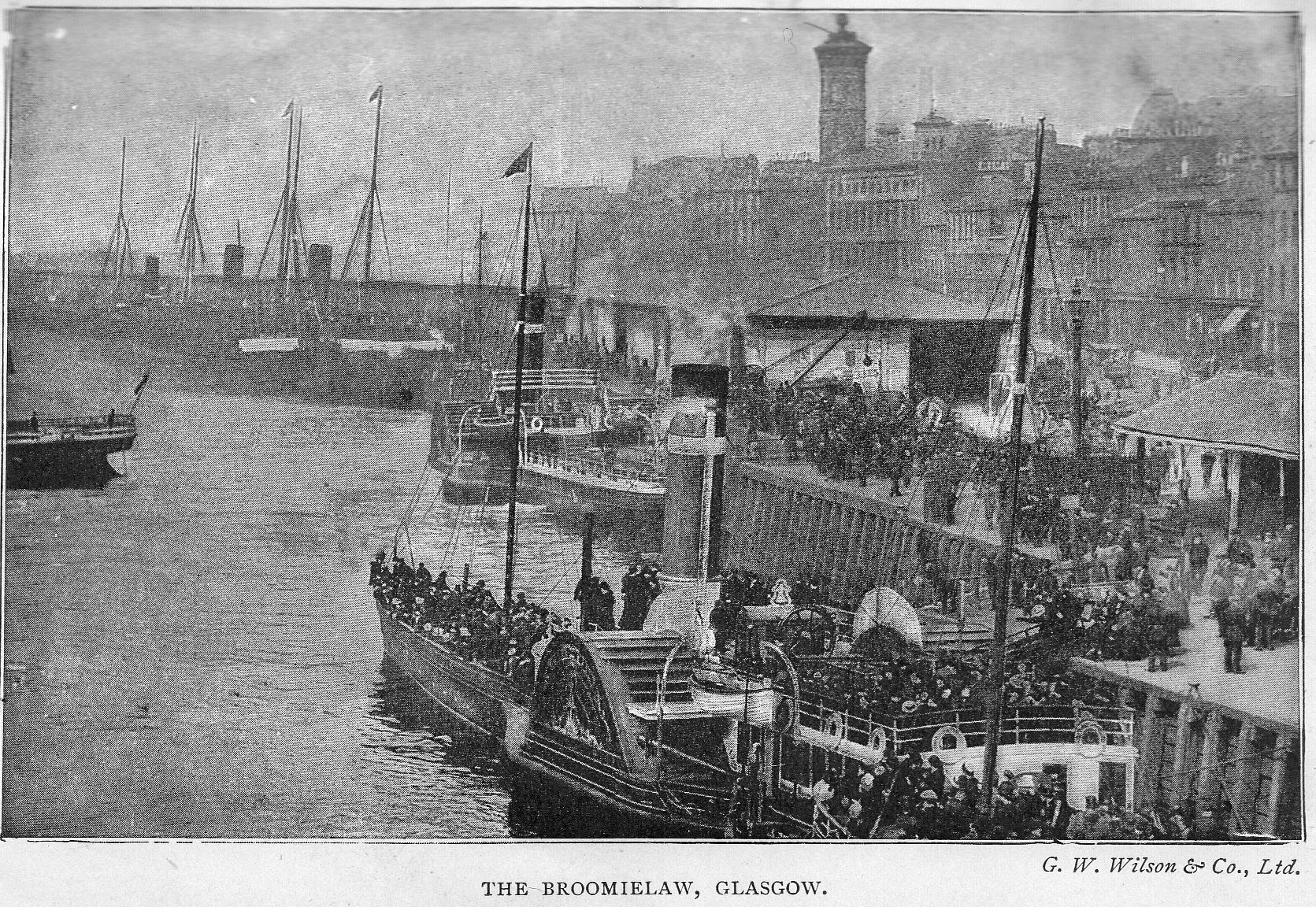

The Broomielaw

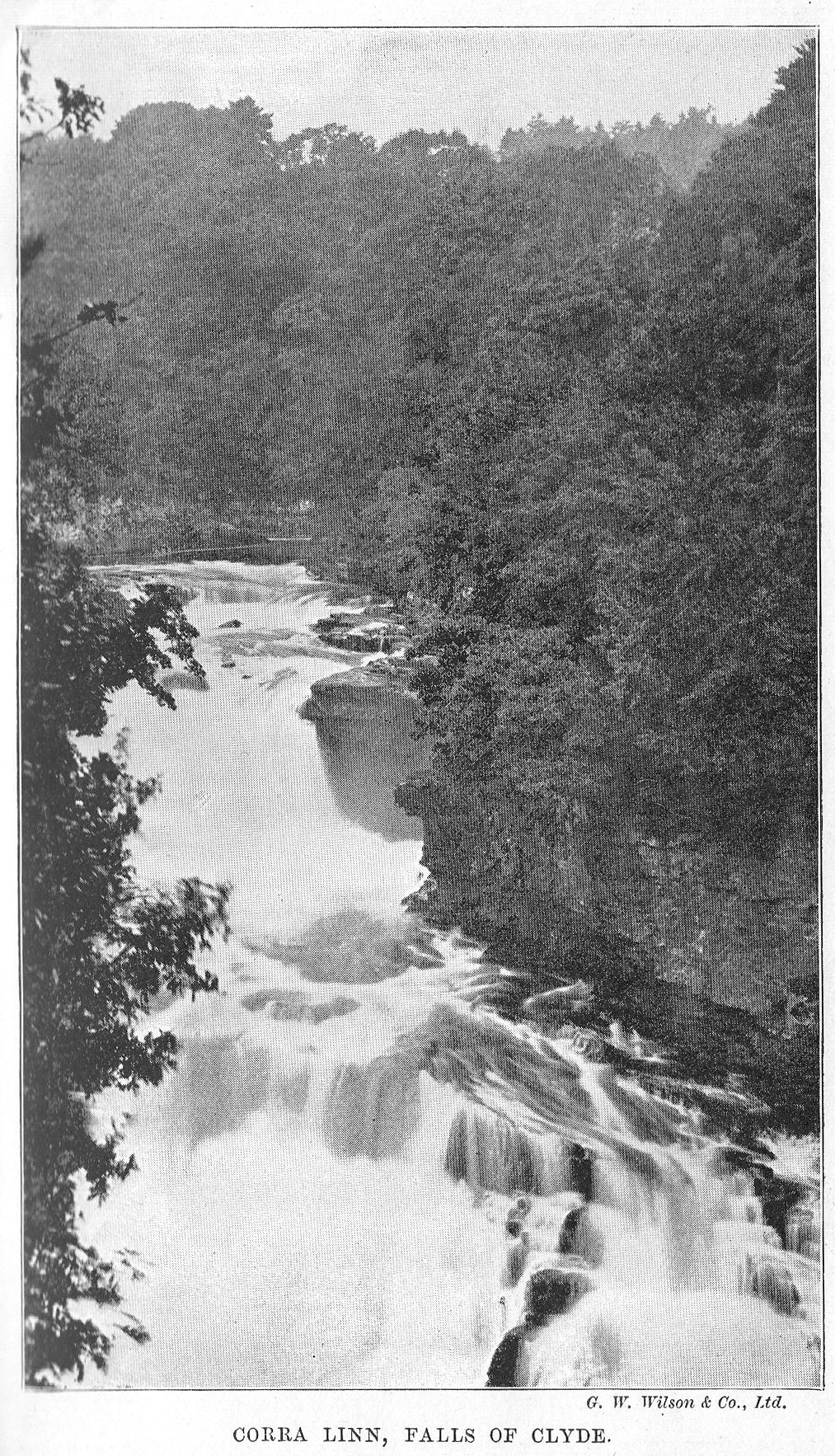

Falls of Clyde, Corra Linn

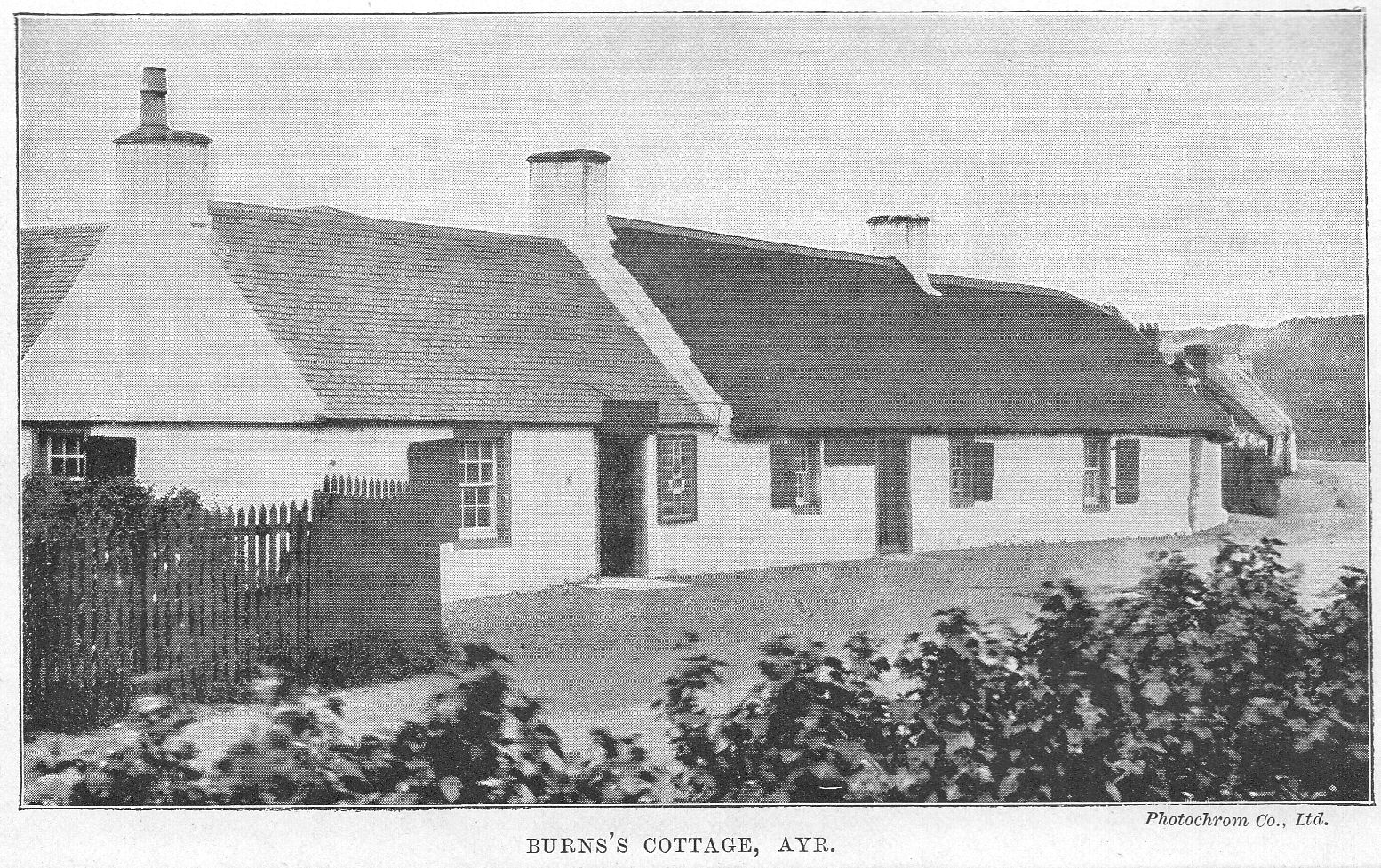

Burns's Cottage, Ayr

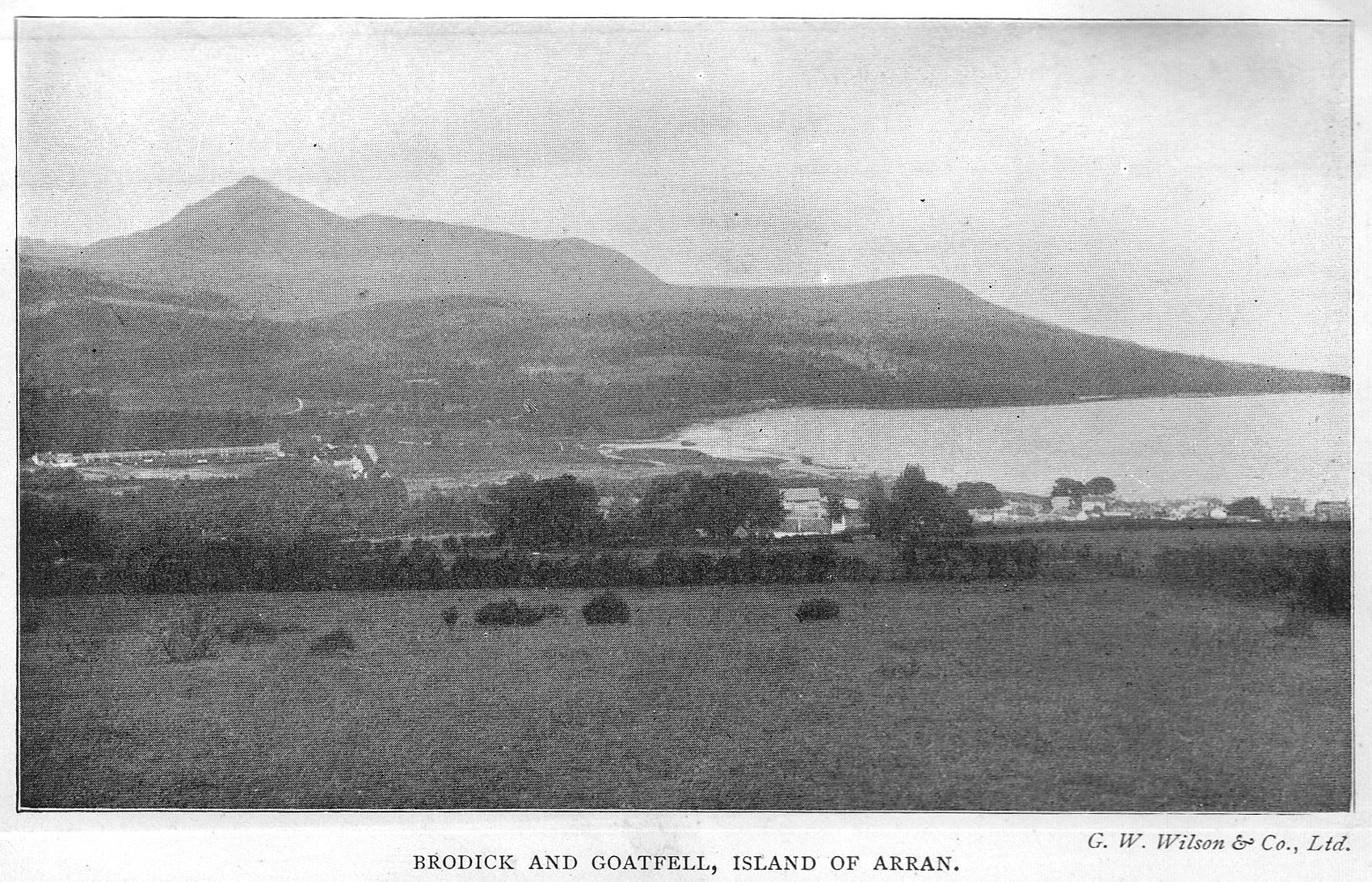

Arran: Brodick and Goatfell

GLASGOW

Principal Hotels. At Railway Stations - CENTRAL (Cal.), Gordon Street; ST. ENOCH (G. & S. W.), St. Enoch Square; NORTH BRITISH, George Square; Family Hotel, * WINDSOR (C), 250 St. Vincent Street; Others - Alexandra, 148 Bath Street; Bath (C), 152 Bath Street; Cockburn (Temperance), 141 Bath Street; Grand, 560 Sauchiehall Street; Royal, 50 George Square; Victoria, 19 W. George Street; Waverley (Temperance), 172 Sauchiehall Street.

Principal Commercial Hotels. Adelphi, Dunlop Street; Steele's, 5 Queen Street, corner of Argyle Street; Blythswood, 320 Argyle Street; George, Buchanan Street; Mackay's, W. George Street.

Restaurants and Dining Rooms. Ferguson and Forrester, 36 Buchanan Street; Queen's, 70 Buchanan Street; Lang's, 73 Queen Street (stand-up luncheon, sandwiches, etc.); White's, 7 Gordon Street;. Scott's, 90-98 Queen Street; Brown's, 79 St. Vincent Street; Grosvenor (New), Gordon Street, opposite Caledonian Station; Corn Exchange, 84 Gordon Street; City Commercial, 54-60 Union Street (Temperance); North British Hotel; Skinner's, Charing Cross. Several first-class Tea-rooms, Cranston's, etc., in Queen Street, Buchanan Street, Renfield Street; Miss Cranston's, Ingram, Argyle, Buchanan, and Sauchiehall Streets.

Post Office, George Square. Open from 6 A.M. to 11.45 P.M.; Sats. 10 P.M. Sundays, 8 A.M. to 9 A.M. Last Desp. S., 10 P.M.

Telegraph Office (in George Square), open at all times.

Returned Letter Branch and Postal Inquiry Office open from 10 a.m. to 4 P.M.

Railway Stations. Central -(Caledonian), for Carlisle and South (per London & N. W. Ry.), Bothwell, Hamilton, Edinburgh, Paisley, Gourock, Wemyss Bay, Ardrossan, and Kilmarnock. Also Low-Level for Dumbarton, Balloch, etc.

Buchanan Street -(Caledonian), for Stirling, Oban and West Highlands, Perth, Dundee, Aberdeen, and the North.

St. Enoch -(Glasgow and South-Western), for Carlisle and South (per Midland Railway), Kilmarnock, Dumfries, Paisley, Greenock, Ardrossan, Ayr, and Stranraer; also City Union Stations.

Queen Street - North British - (High Level), for Edinburgh, Fife, Dundee, Perth, Aberdeen, the South by East Coast, Fort-William (West Highland), etc.; (Low Level), Dumbarton, Helensburgh, Balloch (for Loch Lomond), to West; - and Coatbridge, Airdrie, Bathgate, Bothwell, Hamilton, to East.

Steamers. - Steamboat Quay and Broomielaw, for all the piers on the Firth of Clyde, also Millport, Arran, Ardrishaig, Oban, Fort-William, Belfast, Londonderry, Dublin, Liverpool. Passengers generally join steamers at Greenock, Gourock, or Craigendoran (Helensburgh), avoiding the upper reaches of the river.

Small Ferry Steamers constantly ply across the river in several places.

Tramways in every direction at minimum fare of half-penny. The principal cars run every few minutes at fares averaging Id. per mile. The chief point of inter-section is at junction of Jamaica Street and Argyle Street, whence every extremity of the city may be reached.

Omnibuses ply on various routes not served by Tramways, and connect with all suburban villages.

Subway. A circular line, serving the purpose of the London "Underground," but worked on the cable system, is carried underneath Glasgow, with stations at various points (St. Enoch Square, the most central), and is of much use. On Sundays the Subway trains do not begin to run till noon.

Places of Interest and Entertainment.

ART - See PICTURE GALLERIES.

BOTANIC GARDENS, with CONSERVATORIES, Great Western Road, Hillhead: free; see p. 316.

CATHEDRAL, top of High Street - free.

CEMETERIES - Necropolis, beside the Cathedral; Janefleld, Great Eastern Road; Sighthill, North of St. Rollox; Southern Necropolis, Caledonia Road; Craigton, Paisley Road; Sandymount, Shettleston; Dalbeth, east end of London Road; Cathcart, New Cathcart; Western Necropolis, Maryhill.

CITY CHAMBERS, George Square; County Buildings and Sheriff-Court, Wilson Street.

CREMATORIUM, within Western Necropolis, Maryhill.

COURT HOUSES, foot of Saltmarket.

EXCHANGES - Royal, Queen Street; Stock, Buchanan Street; Corn, Hope Street.

FOSSIL GROVE, in Whiteinch Park, west of Partick.

INFIRMARIES - Royal, close to the Cathedral; Western, Gilmorehill, near the University; Victoria, Queen's Park; and several others.

LIBRARIES - University, with Hunterian Collection; Mitchell, 23 Miller Street; hours 9.30 A.M. till 10 P.M. - Free. Stirling's, 48 Miller Street;; hours 10 A.M. till 10 P.M. - Free. for Consultation. Mechanics', 38 Bath Street. Athenaeum, St. George's Place. Philosophical Society, 207 Bath Street. Physicians', 242 St. Vincent Street. Procurators', 62 St. George's Place. Baillie's, West Regent Street. Also nine Public District Libraries.

MILITARY BARRACKS-Maryhill.

MUSEUMS - Hunterian, University, Gilmorehill. OBSERVATORY, ETC. - Victoria Circus, Dowanhill.

Music HALLS - Empire; Palace; Coliseum, etc.

PARKS - Kelvingrove, west end of Sauchiehall Street; Queen's, Victoria Road, south side; Alexandra, off Duke Street; Green, east from Cross; Cathkin Braes, near Rutherglen, etc.

PICTURE GALLERIES - Art Gallery and Museum. Branches at Glasgow Green (in People's Palace and Winter Garden), and at Camphill. Institute of Fine Arts, 175 Sauchiehall Street.

THEATRES - King's, Bath Street; Royal, 77 Cowcaddens; Royalty, 70 Sauchiehall Street; Grand, 190 Cowcaddens; Royal Princess, Main Street, Gorbals; Metropole, Stock well Street. CIRCUS - Sauchiehall Street. Lyceum Theatre, Govan, etc.

UNIVERSITY - Gilmorehill, Kelvingrove Park.

ZOO – HIPPODROME - New City Road.

GLASGOW, the second city in Great Britain, is not apt at first to inspire any great admiration in visitors, and the reason is obvious; the city is strictly utilitarian, and all the inevitable attendant drawbacks of manufacture, the noise, the dirt, the smoke, are very apparent. It is not until these things are disregarded that the real wonder of this great hive of commerce, its enterprise, its energy, and its administration can be appreciated. The streets are full of men and women eager to work, hurrying to and fro; electric tramcars laden with passengers pass every few seconds; looking down from the railway bridge to the Broomielaw, as the harbour is called, numbers of steamers are ever arriving and departing, and men, swarming like ants, load and unload. The history of the city, which is given below, is a romance of commerce; enormous has been the growth in a comparatively few generations. The town is really in Lanarkshire, but has largely overflowed into both Renfrewshire and Dumbartonshire. It is very hilly, and at the west end the streets are often mere terraces connected by short streets as steep as house-roofs. The spurs of the Scottish Highlands come within a few miles, reaching the shores of the Clyde as the Kilpatrick Hills at Old Kilpatrick, 10 miles below the town, and thence passing in a north-easterly direction as the Campsie Hills. These ranges bound the horizon to the north-west and north of the city; but, catching the moisture-laden breezes from the western sea, they cause a considerable precipitation of rain in their neighbourhood, and thus the rainfall of Glasgow reaches the high annual average of 45 inches.

History and Population. - All the magnificent growth and development of Glasgow has taken place within the last two centuries. It was not until 1690 that a charter was granted to the city creating it a royal burgh; before that time it had been an ecclesiastical town, a burgh of barony under the Bishop. Rutherglen, now a mere suburb, was a royal burgh long before its neighbour, and is in fact the only burgh that owns a charter granted by King David (d. 1153). But Glasgow is not lacking in early records, for about the middle of the 3rd century a Christian missionary, St. Ninian, established himself in a cell on the banks of the Molendinar at Glasgow; and after he departed the place was left to heathendom until the sixth century, when the patron saint, Kentigern, familiarly known as Mungo, settled by the river, and began his missionary efforts (see p. 306). It is not till 1116 that Glasgow again emerges into light, with the reconstitution of its Bishopric. In 1176 Bishop Joceline held office, and his efforts on behalf of the town were so zealous that he may almost be spoken of as the real founder of Glasgow. For his labours in regard to the cathedral see p. 307; but he did not confine himself to that only, he obtained from William the Lion the grant of a burgh with a weekly market, and later an annual fair, which from 1190 has been held unbrokenly to the present day. It begins on the Thursday of the second week in July and lasts a fortnight.

In the time of Mungo the place now known as Glasgow is mentioned as Cathures; when and why the later name arose is not known. It is of Celtic derivation, and among other suggested meanings that of "the grey smith," "the grey hound," "the dark glen," and "the dear family" may be noted. Of these the first, with its suggestions of hard work amid a pall of smoke, is certainly the most suitable at the present time, however different the conditions may have been in the far past.

Glasgow has been the theatre for several actions in the great drama of her country's history; Sir William Wallace overcame an English garrison in the streets. He routed his foes so that they fled to Bothwell, there to re-form and wait for reinforcements. Queen Mary was several times in Glasgow, notably when she visited her sick husband in order to decoy him to his doom (see p. 304). Her last engagement was fought at Langside, a battle, which though merely a skirmish in itself, decided the fate of the kingdom (see p. 318). During the Covenanting wars Glasgow played an active part, being in the centre of events. It was occupied by Claverhouse after his defeat at Drumclog. In 1679 Prince Charlie and tattered remnants of his disheartened army passed through the town in his retreat from England, when his hopes were at zero. The Prince held a review on Glasgow Green before resuming his march to the north. But these scenes are small in comparison with the great story of trade development.

Strange as it may seem, it was the discovery of America which gave Glasgow the first impetus on her successful career. Her position enabled her to take advantage of the new opening. Tobacco and sugar became her staple imports, and by the outbreak of the War of Independence she controlled half the tobacco trade of the kingdom. It was also after the discovery of America that she found herself in a new position, being one of the most important of the ports of embarkation for the new land. The Union with England may be noted as the second of the changes which sent up her trade records by leaps and bounds. To quote from the able preface in The Handbook on the Municipal Enterprises:-

"At that time the population was not more than 13,000. ... In 1740 it numbered 17,000, forty years later it was 43,000; the first official census of the United Kingdom in 1801 gave the population as 83,769. One hundred years later, in 1901, the population within the limits of the municipality was returned at 760,423, but, adding to that the inhabitants of Govan, Partick, and Kinning Park, which, though under distinct municipal control, are parts of the city, the total amounts to 904,948. Allowing for the growth of the city since 1901, and taking into account suburban population not under municipal authority, the inhabitants of Glasgow at this day certainly exceed 1,000,000."

The municipal motto quoted briefly as "Let Glasgow flourish" has no doubt sometimes jarred on those who see in it only egotism, but the whole sentence, "Lord, let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of Thy Word," conveys an entirely different impression. The armorial bearings of the city contain a tree, a bird, and a fish with a ring in its mouth, commemorating three of the most notable miracles wrought by St. Kentigern.

Thu city, no doubt, owes much to its position and resources, but still more to the courage and energy which has been a characteristic of its sons. Its site has already been briefly noted. The river formed a highway for trade, but in early days there lay a long stretch between the city and the limit of incoming sea vessels; in fact, there were about fifteen miles of sand-banks and shoals, obstacles which required millions of money for their removal. Attempts to clear the obstruction were made in the 16th and 17th centuries, and in the latter a port and harbour were established at Port Glasgow; but this was a failure from the first. In 1759 an Act of Parliament for cleansing and deepening the channel was obtained, and ever since the work has been continued at a total cost to the Clyde Navigation Trustees of something like eight millions.

This enterprise answered in an unlooked-for direction; besides the great increase of already established trade, a new branch was opened, that of shipbuilding, in which Glasgow has ever since been pre-eminent, not in Britain only, but in the world. The launch by Henry Bell of the "Comet" of three-horse power, the first European steamboat in 1812, inaugurated the vast industry, and the record was reached in 1902 when 312 vessels of 516,977 tons and 458,870 horse power were launched in in the aggregate from the many mighty yards. It is a scene one never can forget if one comes up the river in the busy time of day, or as the wintering light turns grime to gold - the activity of myriads of men creating mighty engines to traverse all parts of the world, with the clang of tens of thousands of busy hammers (see p. 317).

But second only to the river as a factor in the prosperity of the city is the situation, which is actually upon a great coal-field with its correlative iron; this puts into the hands of her manufacturers two of the indispensible requisites for their work. The coal-fields of Lanarkshire are the richest in the world, and the yearly output now amounts to 17,000,000 tons. In 1828 Neilson's hot blast iron furnaces first came into use, being tried at the Clyde iron-works; the remarkable economy thereby effected developed the iron industry of Scotland at a rate which long distanced all competition. Glasgow is exceptional in having blast furnaces actually within her municipal bounds. Great forges with powerful steam hammers and other appliances, pipe-founding works, and malleable-tube works, boiler-making, locomotive engine building, sugar machinery, sewing machines, and general engineering are among others of the most important industrial enterprises of the city.

Bleaching and calico printing were established in Glasgow earlier than in Lancashire; and these industries still prosper. In fact, here chlorine was used for bleaching before it was introduced into any other British locality, and its introduction was due to the advice and information James Watt communicated to his father-in-law. In Glasgow, also, bleaching powder (chloride of lime) was discovered by Mr. Charles Tennant, who thereby laid the foundation, not only of the gigantic St. Rollox chemical works, but gave the first impetus to the chemical industries generally. From remote times hand-loom weaving was the principal occupation in many rural villages around Glasgow; and with the steam-engine discoveries of Watt, and the inventions of Arkwright, Hargreaves, Cartwright, and others, the textile industries came to be centred in great factories, and these, for now a century past, form one of the leading industries of the city.

Among a host of her sons distinguished for mechanical invention we may mention also the names of Joseph Black and Lord Kelvin.

Perhaps no city in the world owes so much to its municipal government as Glasgow, and this fact is worthily typified by the City Chambers, which can only be described as magnificent (see p. 302). The Municipal Corporation supplies the city with gas, electric light, and water; it owns the tramways, markets, parks, galleries, baths, and washhouses, etc., and has a telephone system of its own. Perhaps the most important of all the municipal activities was that of 1855, when the Corporation acquired the right to bring a plentiful supply of good water from Loch Katrine; and this was supplemented by a second line of aqueduct in 1885. These aqueducts are about 23 and 25 miles in length, and are capable of discharging 110,000,000 of gallons of water per day into the service reservoirs. In order that the water of the loch might be kept free from pollution, the feuing rights over the whole drainage area of Lochs Katrine and Arklet were, in 1892, acquired by the Corporation at a cost of £17,000.

There are few relics left of ancient Glasgow, and the growth of modern times has obliterated any traces of the early city. In the year 1866 an Improvement Act was obtained by the city, the operations under which have served as models for all other great commercial towns. The works have been carried out at a cost of over £2,000,000, but by the realisation of the property in the possession of the Trust, the total cost to ratepayers has only been £568,386. Many streets have been entirely reformed; and in others dens of squalor have been swept away. Model dwellings and "family homes," suitable for the poorest classes, have been constructed, and the Alexandra Park has been formed. Excellent sanitary supervision and an unequalled water supply being maintained, Glasgow has now become one of the healthiest cities in the kingdom.

Three large terminal Railway Stations bring traffic to the heart of the town, respectively serving the three great Scottish Companies - the Caledonian, North British, and Glasgow and South-Western. By means of these railways and their local branches, as well as by the magnificent fleet of river steamers, travelling facilities to and from the city in all directions are very great. From the Alexandra Park, on the north-east, to Pollokshields, south-west, the City Union Railway traverses the town, and connects the North British Bathgate line with St. Enoch station and the South-Western system. Two underground railways, belonging to the North British and Caledonian Railway Companies respectively, have their chief stations beneath the high-level termini of those companies, and form connections with the suburbs; also with Dumbarton, Helensburgh, and Loch Lomond to the west, and Hamilton to the south-east. A circular cable subway has its principal station in St. Enoch Square, whence it proceeds round by Kelvin Bridge, Partick, and Govan. Within the city electric trams traverse almost every important thoroughfare, and run into the suburbs.

As has been said, Glasgow is not a city that particularly impresses a visitor at first sight, nevertheless there are several things which a visitor ought certainly to see, among which may be mentioned The Cathedral, the Art Gallery and Museum, The City Chambers, and the Botanic Gardens, not to mention smaller things. The plan we have chosen is that of giving an account of each of these objects as we come across it in a general survey of the city itself.

It may first be premised, however, that Glasgow is an expensive place to stay in, the hotels at the great railway stations have vied with each other in becoming more and more magnificent, and charge accordingly; as they have unlimited custom they have no need to condescend to those whose purses are not well stocked.

George Square is in many senses the real centre of the city and here we may start our general account. On its north side in the principal station of the North British Railway. The western side is occupied by the Merchants' House and the Bank of Scotland. On the south side the principal building is the Central Post-Office. The whole of the eastern side is occupied by the City Chambers. (See below.) The Square is wide and open. Seats, which are generally fully occupied, are placed about at intervals in the central space, the middle of which is occupied by the Scott monument, which, if not so striking as that at Edinburgh, has the merit of having been the first erected to Scott in his native land. It consists of a fluted column 80 ft. high, surmounted with a colossal statue. Flanking it, on east and west, are equestrian bronze statues of Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort, of no great artistic merit. There are also, round the Square, figures of James Watt, by Chantrey; Sir John Moore (a native of Glasgow), by Flaxman; Lord Clyde (also a native), by Foley; Dr. Thomas Graham, formerly Master of the Mint, by W. Brodie, R.S.A.; James Oswald, M.P.; Dr. David Livingstone the traveller, Thomas Campbell the poet, and Sir Robert Peel, all by John Mossman; Robert Burns, by George E. Ewing; and Rt. Hon. W. E. Gladstone, M.P., near the City Chambers, unveiled by Lord Rosebery in 1902, and designed by Hamo Thorneycroft.

City Chambers

City Chambers. Glasgow has grown so fast that four times within a century have the municipal offices required enlargement. In 1810 the offices were removed from the ancient Tolbooth to the buildings facing the Green, now used as a Justiciary Court. Thence, in 1842, they were transferred to new buildings in Wilson Street, now occupied as a Sheriff-Court and County offices; and, in 1875, they were moved to Ingram Street, where a building was erected forming one block with the Sheriff-Courts, etc. Within a very few years this increased accommodation was found to be quite inadequate, and now a building which easily takes a foremost place among its kind all over the world has been erected. The designs were by William Young of London (a native of Paisley); and the whole building is in the Venetian Renaissance style. The Council Chamber is placed over the grand entrance, facing George Square; and the Banqueting Hall, with suite of reception-rooms, occupies the George Street frontage. The centre and wings of the principal elevation to George Square project and rise an additional story, the centre being capped with a pediment flanked by two domed towers, and the wings end in domes and lanterns. In the centre, over the entrance loggia, a tower rises about 100 ft. above the main parapet - in all more than 200 ft. from the street level. The building is enriched by statuary groups and figures (Geo. Lawson, H.R.S.A., and others). But splendid as is the exterior, the interior will strike a stranger with even greater admiration. The employment of alabaster, marble, and coloured tiles in the principal staircases, halls, and corridors produces an effect of magnificence not easily to be surpassed. The entire cost of the pile, including £170,000 for the site, exceeded £500,000.

George Square lies in the very heart of the city, and close to it are the principal places and most important streets. The three great railways have already been noted. Queen Street Station, the terminus of the N. B. R., is on the north side of the Square. The principal stations of the other two are St. Enoch's (G. & S.W.) at the foot of Buchanan Street, and the Central (Caledonian) in Gordon Street. Nearly all the streets here lie at right angles.

At one time St. Enoch Square was a rural churchyard with a church dedicated to St. Tanew, the mother of Kentigern, a name which, by a strange corruption, became Enoch.

The streets running north and south are well supplied with excellent shops, of them all perhaps Buchanan Street is the most important. In it are the fine offices of the Glasgow Herald. An arcade filled with shops leads off from the eastern side near the south end.

In Queen Street (east) is the Royal Exchange, and in Ingram Street is Hutcheson's Hospital, which corresponds in some ways with Heriot's Hospital in Edinburgh.

In Miller Street is the Mitchell Library, which is Glasgow's public library. It originated in a bequest by Stephen Mitchell, a native of Linlithgow, who carried on a tobacco manufacturing business in Glasgow, and died 1874. The amount he left for this purpose was close on £67,000. Many bequests to the library have since been made, of which the most important is that of Robert Jeffrey, of over 4000 volumes, some of them works of great rarity and value. The library now contains over 180,000 volumes and has outgrown its space. A new building is to be erected between St. Andrew's Halls and North Street. There are branch libraries in connection in almost every suburb; to the erection of these Mr. Carnegie has contributed £100,000. In Miller Street is also Stirling's Library, and Baillie's Library is in West Regent Street; both open to all comers for reference. Near the foot of Glassford Street (made later) once stood Shawfield House, belonging to Campbell of Shawfield, who, with the compensation received for the damage done to it in the Malt Tax riots of 1725, bought Islay. Twenty years later Prince Charlie stayed here and met Clementina Wulkinshaw, by whom his life was to be so deeply influenced. It was bought in 1760 by John Glassford, one of the "Tobacco lords," who strutted about in his scarlet cloak and curled wig, with his cocked hat and gold-headed cane, as gay as any courtier. 1t was after him the street was named.

Passing farther eastward, we come to High Street, running roughly north and south, and traversing the older part of the town. At its intersection with the Trongate stood the old Cross of Glasgow, once the centre of the city. This part has been much altered by modern improvements, and nearly all the old houses - in many cases, it must be confessed, very insanitary and squalid even if picturesque - have been swept away. At the north-west corner of the two intersecting streets stood the ancient Tolbooth or prison, five stories high and turreted. It will be remembered that it was here young Osbaldistone visited his friend in distress; during which visit he discovered to his astonishment that his mysterious guide was none less than Rob Roy the redoubtable cattle-stealer himself (Rob Roy). The contiguous building in the Trongate is now all that remains of the old town hall, and it is cut up into shops. When Defoe visited Glasgow in 1726 there were colonnades or piazzas in front of the houses of the four streets radiating from the Cross; these called forth his praise, in spite of the meanness of the small shops they sheltered and darkened. It was in "Donald's Land," on the north side of the Trongate, that Sir John Moore was born.

In the middle of the street is a equestrian statue of William III. presented to the burgh in 1735 by James Macrae, Governor of Madras. Near it is one of the accesses to the underground line of the Caledonian Railway. On the south side of the street projects the Tron Steeple, a venerable but stunted spire, dating from 1637. This forms an arch over the pavement. We are now in the centre of old Glasgow, though little enough remains of it. To the north is the High Street mentioned below. An ancient street called Drygate originally led from the Cross, and in the upper part of it was the house in which Darnley lay sick when Queen Mary came to seek him, to condole with him, and to lure him with all her charms, until he consented to be carried forth in a litter to journey with her to Edinburgh, where he was to meet his awful fate. Eastwards is the old Gallowgate, and southwards the Saltmarket, for ever associated with Bailie Nicol Jarvie. The name arose from the fact that the salt for pickling the salmon caught in the river was sold here. The south end is called Jail Square, and here was formerly the place of public execution. The Court-House, as we have said, served for a time as the Municipal offices. The whole of the Saltmarket is modernised.

Off the Saltmarket runs the Briggate, a once fashionable and busy street, which led to the ancient bridge of the city. Notwithstanding its intersection by railways, the Briggate is one of the few streets in Glasgow which still wears a 17th-century aspect. Near its farther extremity there yet remains the Briggate Steeple, now maintained by the Corporation as a relic of the Merchants' House, built in 1659 by Sir William Bruce of Kinross, the architect of the more modern part of Holyrood Palace. In the words of McUre, the Glasgow historian, "the steeple is of height 164 foot, the foundation is 20 foot square: it hath three battlements of curious architecture above one another, and a curious clock of molton brass, the spire whereof [of the steeple] is mounted with a ship of copper finely gilded in place of a weather-cock."

Before leaving this part we may just mention Glasgow Green, the park of the people. The park has a frontage on the river of about 1and-a-quarter miles. It is perhaps the worst placed of all Glasgow's parks for vegetation, being in the thick of the drifting smoke, but nevertheless of late years much has been done to improve it. The two little streams, the Molendinar (see p. 297) and the Camlachie, ran across it, and when these became mere sewers they were covered in. The Nelson monument was put up in 1805, and is as much a rendezvous for the discontented ranters of Glasgow as Hyde Park is for those of London. The Doulton fountain, which was exhibited at the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888, is a really fine piece of work. The People's Palace and Winter Garden, were opened by Lord Rosebery in 1898, and in the former there is often a fine loan collection of pictures to be seen.

If we follow the High Street northwards, we pass the prison and ascend what is called the

For over four hundred years the University was in the High Street; the site may be identified by the present College Station. Many are the footsteps of men who have become famous that we might hear if we listened to the echoes of history; among them we must mention one, a native of Glasgow by birth, Thomas Campbell the poet, b. 1777, tenth child of his father, who at the early age of thirteen printed and sold to his fellow-scholars verses of his own composition. He was later Bursar and then Rector of the University. In the old building of the University worked also Smollett, Lockhart, "Christopher North," and Tait, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury. The College stood partly on the site of the old Monastery of Blackfriars.

Soon after we come to a striking group formed by the cathedral backed up by the rising ground of the Necropolis.

The Cathedral

Admittance daily 10 A.M. till dusk or (in summer) 6 P.M. No gratuities. Service on Sundays 11 A.M. and 2 P.M.

The Cathedral has the distinction of being the only old minster in Scotland besides that at Kirkwall which is still in good preservation. At first sight it is rather disappointing, being of no great size, and with a smoke-blackened exterior, and rather ungraceful spire; but after visiting the interior, and especially the crypt, its great charm - the charm which venerable age and good workmanship must always produce - will be felt.

Sir Walter Scott, by the mouth of young Osbaldistone in Rob Roy, doubtless spoke his own opinion of it in the following words:- "The pile is of a gloomy and massive rather than an elegant style of Gothic architecture; but its peculiar character is so strongly preserved, and so well suited with the accompaniments that surround it, that the impression of the first view was awful and solemn in the extreme. ... We feel that its appearance is heavy, yet that the effect produced would be destroyed were it lighter or more ornamental."

The Cathedral is dedicated to St. Kentigern (p. 297), who came from the Orkneys on his missionary errand to the district of Glasgow, then called Cathures, about 539; he was subsequently expelled by the king or chieftain, and took refuge in Wales, where he founded the See of St. Asaph. He was recalled by the successor of his persecutor, and about 560 erected the earliest church on the site of the present Cathedral. He is said to have died in 603, and was buried at the east end of the ground on which the Cathedral stands. For more than five centuries nothing further is heard of the church in Glasgow. It was probably of wood, and possibly fell to pieces gradually, though it is likely that many pilgrims were attracted by the shrine of so great a saint. King David, whose mother was St. Margaret, came to the throne of Scotland in 1124, having previously held the Lowlands as Earl. He founded the See of Glasgow, made his tutor, John Achaius, bishop, and endowed the first cathedral, dedicated 1136, which was built on the site of St. Kentigern's church. Of this cathedral there remains nothing. Succeeding bishops added and restored, and the earlier part of the existing building may be attributed to Bishop Ingelram (1164). A mere fragment of this remains, and may "be found about twenty feet from the west end of the interior of the south aisle of the present lower church," and consists of nothing more than "a foot or two of splayed bench table, a single wall shaft of keel section, with its unfinished octagonal capital, and its base with large square plinth, and a few stones of walling" (P. Macgregor Chalmers). Bishop Joceline began adding to his predecessor's church, which, while he was actively engaged in repairing it, was partially burnt. Of his rebuilding a considerable part remains, including the south aisle, and the north wall of the north aisle of the lower church, but the bishop died before the completion of his great scheme, and it was not until the time of Bishop Bondington (1233) that Joceline's unfinished choir was removed and replaced by the present one. It was Bishop Robert Wishart (1272) who took the nave in hand, and it is to Bishop William Lauder (1408) that we owe the design of the beautiful Chapter-Rouse. Bishop John Cameron (1426) practically completed the work; he finished the Chapter-House and built the spire of the cathedral. He also made a Consistory House and Library which stood at the south-west angle, and were completely destroyed in 1846.

Having in this very brief and summary sketch indicated something of the growth of the building, we may turn to it as it now stands.

The style is Early English, though differing greatly in one part and another. The absence of chairs or any kind of seats in the nave adds greatly to the effect, as the whole can be seen in one fine sweep. The arches in the aisle arcades are sharper than those in the choir, and the whole is characterised by a greater simplicity, though it must be remembered the nave is of the later date. Behind the plaster ceiling is the original wooden roof of oak, unfortunately hidden. There are clerestory and triforium to see, both worth notice. Looking up toward the choir the first impression is one of disappointment, for the rood-screen which separates the two is very heavy, and pierced only by a low door. It is but fair to add that this screen, due to Bishop Blacader (1484), has been greatly admired, and is in itself a fine piece of work, with a parapet of good tracery, but it is against present day ideas that such a cumbersome obstacle should break the vista of a beautiful cathedral.

The Choir itself is very grand. It is raised considerably above the nave, standing over the Lower Church. The chief feature, the moulding, is seen best on the capitals of the piers. One peculiarity is a chapel of four altars behind the high altar; this corresponds with the better-known Chapels of the Nine Altars at Durham; like that cathedral also Glasgow ends now squarely, but is conjectured to have once finished in the apsidal form. The choir is used for service and is called the High Church. In the north-east corner of the High Church is the entrance to the Sacristy.

Returning once more to the nave, we note that there are no real transepts, only the foundations or lower part of the southern transept, in itself a perfect little chapel. This used to be known as the Dripping Aisle from the perpetual dropping of water from the roof, a peculiarity which no longer continues. It shows that probably transepts were at one time contemplated in the plan of the building. But the chief feature of architectural interest is the Lower Church or Crypt, which has already been more than once referred to. It follows the general plan of the choir above. To the least knowing the design of the pillars must appear curious. The four in the centre form a square, indicating the position of St. Mungo's Shrine, which remained until the Reformation. The design of the vaulting and the carving on the bosses should be especially noted, but it is a drawback that it is often so dark as to be difficult to distinguish the features of interest. It was in this crypt that Scott placed one of the notable scenes of Rob Roy. In the south-east corner is St Mungo's Well, the traditional spot on which the first saint founded his church. At the east end is an old statue, popularly said to be St. Mungo's tomb, but in reality probably connected with the tomb of the famous Bishop Wishart. Edward Irving, founder of the Catholic Apostolic Church, is buried in the crypt, and there is a memorial window to him executed by Bertini of Milan.

In the north-east corner of the crypt, below the Sacristy, we find the beautiful 15th century Chapter-House, though the foundations are of a much earlier date. The doorway is well moulded, and the groined ceiling is supported by a slender shaft 20 feet in height. What is known as the Covenanters' Stone, recording the names of some who were killed in those disturbed times, is now to be seen here.

About the middle of the 19th century a general restoration of the Cathedral took place, when the ancient tower and Consistory House on the west face of the Cathedral were removed, an indiscretion which has been lamented more on antiquarian than on architectural grounds.

Cathedral Windows

It was also decided to fill in the windows with stained glass. The eastern window, one of the finest of the series, was presented by Government. The first window was erected in 1859, and the last in 1864, when the whole (81 in number) were formally handed over to the Crown. The windows in the nave, transepts, and Lady Chapel were all executed at Munich; those in the chapter-house and crypts by various British and foreign artists, whose names, as well as those of the donors, are given in the descriptive catalogue sold in the Cathedral. The subjects are arranged with a certain regard to chronological order, commencing at the north-west corner of the nave with the expulsion of Adam and Eve, and continued to the south-west angle with other Old Testament characters. The great west window contains subjects taken from the history of the Jews: and the north transept window figures of the prophets and John the Baptist. The subjects in the choir illustrate the parables; those in the Lady Chapel are figures of the apostles; and those in the great eastern window the evangelists. The clerestory windows are as yet only partially filled with stained glass.

The revenues of the See of Glasgow were at one time very considerable, as, beside the royalty and baronies of Glasgow, 18 baronies of land in various parts of the kingdom belonged to it. Parts of these revenues have fallen to the University of Glasgow and part to the Crown.

Among the line of Bishops there are many men of learning and dignity above the average; particularly noticeable is the name of Bishop Robert Wishart (1272), a firm friend of Wallace and Bruce, who furnished from his own wardrobe the robes in which Bruce was crowned. For this act he suffered imprisonment for some years at the hands of Edward I. The See of Glasgow was made Archiepiscopal in 1491 at the instance of James IV., who was an honorary canon of the Cathedral. Among the Archbishops the names of Bishop Burnet and Leighton stand out. During the fit of destructive enthusiasm which followed the Reformation the building was saved from injury by the zealous activity of the craftsmen of Glasgow, who forbade the fulfilment of an edict which had gone forth for the destruction of the "idolatrous monument." The structure was carefully repaired by certain of the Protestant Archbishops, notably by Bishop Law, whose monument may be seen in the Lady Chapel.

On the exterior of the cathedral the great tower and spire should be noted, and the gargoyles projecting from the parapet, especially those on the north side, which are in good preservation and very original.

The Bishop's Palace or castle, now vanished, stood a little S.W. of the cathedral, nearly in front of the present Royal Infirmary, the remains were removed in 1789 to make way for that building. The principal architectural feature of the Infirmary, which was designed by brothers Adam, and opened in 1794, is the central dome, which forms a roof to the lecture and operating theatre. In front of the building is a bronze statue of Sir James Lumsden, a former Lord Provost. To the north of the Infirmary are new buildings for the Medical School.

The Necropolis

From time immemorial this part has been associated with the burial of the dead. St. Ninian made a burying-ground, on the site of which now stands the Cathedral, for it was to this spot that the untamed oxen led the body of Fergus, thus deciding St. Kentigern here to fix his cell. Somewhat similar tales are told of many great cathedrals. The present Necropolis is on a steep conical hill rising from the valley of the little Molendinar stream, and with its trees and various monuments it forms a striking background to the Cathedral. Across the valley is a light bridge called the Bridge of Sighs, from the many sorrowful processions that have wended across it. The cemetery is the property of the Merchants' House, and was known at first as the Fir Park. In 1824 the tall column surmounted by a statue of John Knox was put up by public subscription, and only subsequently did the idea of making the place a public cemetery occur to any one. It cannot, of course, bear comparison with the well-known Tomnahurich cemetery at Inverness, but it is a noticeable spot. The column to John Knox stands up above its fellows, but there are other monuments also conspicuous, namely those to William Black, William McGavin, George Coventry, Rev. Dr. Heugh, Charles Tennant of St. Rollox, Principal Macfarlan, the poet Motherwell, Sheridan Knowles, and Edward Irving (see p. 308). In one corner of the Necropolis is the Jews' burying-ground, in which the first body was laid in 1832.

There is a good view of the city from the summit of the Necropolis, which rises to a height of 200 or 300 feet.

St. Rollox

Passing in a line with the High Street by the Royal Infirmary, northward through Castle Street (so named from the Bishop's Castle), the Monkland Canal is crossed, and the visitor at once finds himself in the grimiest of manufacturing regions. On the one hand are the great works of the Caledonian Railway Company. On the left hand, stretching along the canal bank, are the famous St. Rollox Chemical Works of Charles Tennant, Sons, and Company. The works are distinguished by the great chimney stalk, 435 ft. high, long the pride and boast of Glasgow, until an ambitious rival erected another a few feet higher, designed by the late Professor Macquorn Rankine. Then we pass the huge Sighthill cemetery.

Farther out still is Springburn with its public park, in which is a winter garden.

The Alexandra Park,

one of the numerous public pleasure-grounds within the city, is situated at the extreme east, and can be reached by tramway from George Square or Duke Street. It was acquired at a cost of £40,000 by the City Improvement Trust, and a considerable additional sum has been expended upon it.

If we return now to George Square we shall easily find our way westward by any of the great east and west running streets, of which the principal are Sauchiehall Street (such a stumbling block to southern tongues) on the north, and Argyle Street on the south. In Sauchiehall Street are the Royalty Theatre, Theatre Royal, and the Empire Palace; and in Berkeley Street, opening off it, are the St. Andrew's Halls, the property of the Corporation, where the orchestra can seat 650 performers. In Sauchiehall Street, too, is the Institute of Fine Arts, where periodical exhibitions of Modern Art take place. At Charing Cross stands the Grand Hotel, and from this point the residential west end of Glasgow may be said to begin.

Argyle Street, which continues all the way to Kelvin Bridge in one direction, and by Trongate and Gallowgate the other, runs roughly parallel to the course of the river for about five miles.

The great feature of the western end of the city is Kelvingrove Park.

Kelvingrove Park.

The Park owes much to its hilliness, for the abrupt rises and falls add greatly to its picturesqueness, and make it seem much larger than it is. From the flagstaff at the east end the splendid buildings of the University can be seen towering majestically on their high ground. Beyond them is the Western Infirmary; and some new buildings in connection with the University. Farther to the left is the handsome red sandstone building of the Fine Art Gallery and Museum.

In the middle distance is a fountain called the Stewart Fountain, well carried out, which serves as a rendezvous for old and young. It was designed in commemoration of Lord Provost Stewart, to whom the city owes its unequalled water supply. Between it and the Fine Art Gallery is the old Museum, whose contents are now transferred to the new one: it houses the Jeffrey Reference Library temporarily. In front of the Art Gallery are two exceptionally good bowling greens. The Park is 85 acres in extent, and was acquired by the Corporation in 1852. It is well laid out, and the flower beds add no small charm to it. It is traversed by the river Kelvin, which, it must be confessed, is a mere muddy brook. In the Park were held the two great International Exhibitions of 1888 and 1901.

The University

The University of Glasgow is second in seniority among Scottish Universities, having been founded by a charter of James III. of Scotland on the instance of Bishop Turnbull, and further confirmed by a Bull of Pope Nicholas V. in 1450.

It was at first established in a tenement in the old street named Rotten Row, not far from the Cathedral, thence in 1460 it was moved to the High Street, and there remained until 1870. At the Reformation it suffered as much as other institutions of its kind, and for some time subsequently lingered on in a very precarious state, but in 1577 it was remodelled. In 1846 an attempt was made to transfer it to a more worthy position, but nearly twenty years elapsed before the project was taken up in earnest. The present magnificent site and worthy buildings cost an enormous sum, which was made up in various ways, partly by the sale of the ancient site, partly by munificent subscription, and partly by the help of the National Exchequer, for Parliament granted no less than £120,000 in six annual instalments. The new buildings, erected on Gilmorehill, as the site is called, were designed by Sir G. Gilbert Scott; the foundation was laid by King Edward in 1868, and two years later they were first opened for classes. There are now thirty-one chairs, and over 2000 students. The eminent men connected with the University have been so many that it is quite impossible to attempt any exhaustive list: a few among the names, however, may be mentioned:- Adam Smith, James Watt, Sir William Hamilton, William Hunter, Edmund Burke, Francis Jeffrey, Thomas Campbell, Sir Robert Peel, Macaulay, the two Lyttons, Disraeli, Gladstone, John Bright; and among those of our own times, Lord Lister and Lord Kelvin.

From the terrace in front one can see the facade of the noble range of buildings with the great spire rising 300 feet from the ground. This was erected in 1888 as the result of a bequest. The latest additions to the University were opened in April 1907 by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, and include the Natural Philosophy and Medical Departments, which cost £70,000.

Otherwise the chief points to note are the Common Hall of the University, known as the Bute Hall, which was the result of a donation of £45,000 from the late Marquess of Bute.

This is one of the most important architectural features of the buildings. It forms the central and main portion of a pile which intersects, from north to south, the great quadrangle, and binds together the various public departments, senate hall, library, reading-room, and museum of the college. The Bute Hall rises over a range of cloisters, and internally is of grand proportions. The fittings throughout are richly wrought in the Gothic style, and a magnificent Gothic screen at the south end separates this noble apartment from the smaller Randolph Hall, which connects with the Senate Hall, etc. At the north end the Grand Randolph Staircase supplies the principal entrance, and gives access also to the reading-room, Hunterian Museum, etc.; the cost of the Randolph Hall and staircase fell on the bequest to the University by Charles Randolph, shipbuilder; and the cloisters were partly erected by public subscription.

In the Museum (open free daily three days a week, 10 A.M. to 5 P.M., and other three days on payment of threepence; closes at 3 P.M. on Saturdays). Besides the usual Mineralogical and Geological details, there is an unrivalled collection of coins valued at £80,000; this, however, is not shown except on special occasions. There is a library attached to the Museum, part of the same bequest, and this contains a valuable series of Caxtons, Pynsons, and other early printed books, also a collection of MSS. the value of which is now only beginning to be realised.

The University Library (open 11 A.M. to 2.30 P.M. in winter, and 11.30 A.M. to 2 P.M. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday in summer) is on the ground floor, and is especially rich in Philosophical and Theological literature. Like every other public institution in Glasgow - surely the most liberal hearted of all cities - it has been enriched by numerous bequests of great value. Of these the two separate Euing bequests are the most remarkable, one consisting of more than 10,000 volumes, many of them of great rarity and value, and the other of a unique collection of Bibles. The library is open to others than those connected with the University on the modest payment of 10s. 6d. yearly.

In close proximity to the University is the Western Infirmary. The institution is largely used for clinical instruction in connection with the Medical School of the University. Adjoining the Infirmary is the Anderson's College Medical School.

Art Gallery and Museum

This Gallery is worthy of the high estimation in which it is held by the city; for it is a splendid building containing a valuable collection.

The origin of the collection is really due to Archibald McLellan, at one time a Town Councillor, who left his collection of valuable pictures to the city; but when it was discovered that his affairs would not in justice allow of such a bequest, the Town Council came forward and purchased the collection. Various bequests and gifts have since been made, and many purchases, until Glasgow stands in the first rank of Art galleries. The collection was at first housed in Sauchiehall Street, but the balance of the money from the International Exhibition of 1888 formed the nucleus of a fund for providing more suitable accommodation. And the Gallery as it now stands is finer than anything of the same kind that London can show.

It is of red sandstone, designed in a French Renaissance style, with large entrances on both the north and south sides. Over the north porch rises a tower flanked on each side by a smaller one, and surmounting it is the statue of Victory in bronze, while the other two bear figures typical of Immortality and Fame. A large group of Sculpture by George B. Frampton, B.A., stands within an open arch in the north porch. This represents St. Mungo protecting Art and Music. The building was opened in 1902, when the collections had been transferred to it. The only weak point seems to be the catalogue, which is arranged in alphabetical order under the names of the artists, instead of corresponding with the rooms of the Gallery. It is full of biographical notes as to the artists, which can be obtained in any book of reference, and gives the baldest details in reference to the actual pictures, not even indicating which are genuine and which are merely of the school of, or after, particular artists. It is a mechanical piece of work. There is also no plan of the building in it, or any indication where to find particular works. As this is so, we attempt to supply the want here by giving a few practical details.

The entrance hall, which is finely carried out in cream-coloured sandstone, and a floor of variegated marble, is devoted to statuary. It rises the whole height of the building, and on the upper storey at one end is a great organ. The statuary is not equal to the pictures, and much of it consists of plaster casts only. The marble statue of Pitt by Chantrey in the northeast corner is the gem of the collection. Subsidiary halls on the ground floor and galleries are devoted to Natural History, Engineering models, etc. In the open galleries, running round the halls on the first floor level, are some pictures and various other objects, such as collections of glass, china, etc., showing the finest work done in the Industrial Arts. The pictures proper are in the saloons on the first floor, and are roughly classified, so far as is possible, in accordance with the conditions of bequests. We note the most striking and valuable in each room in passing, a task rendered easier because the title and artist's name are in all cases on the frames.

Beginning with the west room on the south side of the building, we have the Old Masters. Flemish - Vandyck, The Repose in Egypt; several of Rubens' works, including his Wild Boar Hunt; a couple of Murillo's; many of the Teniers', father and son; Van Der Goes' St. Victor with a Donor, counted as the chef d'oeuvre of this master, and worthy of careful scrutiny. Dutch - in first small room Sir Godfrey Kneller's William of Orange; in larger room many of Rembrandt's, including his Man in Armour; there are also here represented Franz Hals, Hobbema, Wouvermans, Ruysdael, etc. Donald Bequest - This is one of the most important as well as the most recent gifts to the Gallery, and if there is time to see only a small number of pictures, this room with the following one should certainly be selected. The bequest consists of works estimated at not less than £40,000 of value. There are three Troyons, the finest being Returning Home; two Millets, including Going to Work; three Corots, including The Cray Fisher and The Woodcutters; Monticelli's Adoration of the Magi; three works of James Maris; Velasquez' Philip IV.; a Turner, and other works by Daubigny, Constable, Orchardson, etc. Old Masters, Italian - Here there are specimens of the works of Botticelli, Titian, Tintoretto> Raphael, Coreggio, Salvator Rosa, Carlo Dolci, and Paul Veronese. Crossing now to the north side we come to a Modern Room, where the chief objects to notice are two Turners, one of them of Modern Italy, exquisite; and others by Millais, including The Forerunner; Alma Tadema, Burne Jones, and Constable.

In the Smellie Bequest room there is nothing particular to note.

Eighteenth Century British and French Art. - On the French side we have works of Coypel, Watteau, Greuze, etc., and on the English, Sir Joshua Reynolds is well represented; also Wilson, "the father of English landscape painting," Raeburn and Morland; whilst somewhat of an anachronism is Whistler's famous portrait of Carlyle at the end of the room. Macdonald Bequest - In this room there are also some sketches of old Glasgow. Modern School - This is not a very brilliant collection, containing a good many portraits of local rather than general interest, and several views of Scottish scenery varying in merit.

There are various branches in connection with the main Art Gallery which receive loans of pictures namely Camphill Gallery, the People's Palace at Glasgow Green already mentioned, and Tollcross Museum. During one week in 1905 over 24,000 persons visited the principal Gallery. The Old Museum has been mentioned; this was built by public subscription as an addition to old Kelvingrove House, which was taken down in view of the Exhibition of 1901. Not far from the Kelvingrove Park northward are

The Royal Botanic Gardens

of 43-and-a-half acres, one of the most delightful of the free spaces of Glasgow. They are open to the public, and stand on high ground. In the centre is a fine range of glasshouses, including the Kibble Palace, a large conservatory and winter garden. Past the Gardens runs the great trunk road called the Great Western Road, straight as a ruler, to the heart of the city. At the east end of the Gardens is Queen Margaret's College for Women. North-westward is Ruchill Park of about 53 acres, near which is the Ruchill Hospital. To the north is the suburb of Maryhill, and beyond it the Western Necropolis and St. Kentigern's Catholic Cemetery.

The River

Before crossing over to the south side it is necessary to make a few notes on the river and bridges. Something has already been said on this subject when the progress of Glasgow as a city of trade was under review. A tidal dam above the Albert Bridge near Glasgow Green limits the flow of the water.

Up to 1768, the old bridge, crossing where the present Victoria Bridge (opened 1856) is, was the only one over the river at Glasgow. Then the Jamaica Street Bridge, or as it is more correctly called Glasgow Bridge, was erected. This has been twice renewed, the last time in 1899. Unfortunately the railway bridge crossing just below it blocks the picturesque view of the Broomielaw with its steamers and busy traffic, and the quay from which the pleasure steamboats start. Not far off is the Kingston Dock, opened in 1867, with 5 acres of water area. Farther down there are two larger docks on the north and south sides respectively, the Queen's and Prince's, opened 1877 and 1897, with a combined area of 69 acres.

Eighteen and a half miles of the river are now navigable.

The shoals and obstacles removed speak well for the patience and enterprise of the Navigation Trust, among them all may be specially mentioned the Elderslie Rock, discovered by the grounding of a vessel in 1854. This extended 1000 feet along the river, and partially across it, and required years of labour for its removal. It gives some idea of the magnitude of the operations which have been successfully carried out, when one knows that from 25 to 29 feet of depth have been added to the channel. A new dock is in construction at Clydebank some 6 miles farther down. Stately examples of naval architecture may be seen at Lancefield, Finnieston, Mavisbank, and Plantation quays on both sides of the water. Engines, boilers, and heavy machinery, are usually put into new vessels at the 75-ton crane at Finnieston. At intervals for some miles farther down the river there occur great shipbuilding and marine engineering establishments, Govan and Clydebank being especially noticeable for their activity. (For further see p. 352.)

South Side

The part of the city lying to the south of the Clyde comprises the districts of Hutchesontown, Laurieston, Tradeston, Kinning Park, and Kingston partly in the barony of Gorbals (these districts are chiefly industrial); beyond which lie the residential districts of Pollokshields, Strathbungo, Govanhill, Crosshill, and Crossmyloof. Eglinton Street, a continuation of Bridge Street, leads straight to Crosshill and the Queen's Park. On the left-hand side, at some distance, are the great blast furnaces and ironworks of William Dixon (Lim.), which nightly illumine the south-eastern sky of Glasgow. The Queen's Park, of about 146 acres, which is to the south side what Kelvingrove is to the north, and Richmond Park, of 44 acres, are both in this quarter. The former, from which commanding views of the city may be obtained, was laid out by Sir Joseph Paxton. The latter takes its name from Lord Provost Sir David Richmond.

Langside

South of Queen's Park is the Victoria Infirmary of Glasgow, opened in 1889. A little beyond is the village of Langside, where Queen Mary met with her final defeat, an event which "settled the fate of Scotland, affected the future of England, and had its influence over all Europe." This battle took place shortly after the Queen's escape from Lochleven Castle. She had been joined by a considerable party of friends, who raised an army of 6000 men, commanded by Argyll, to reinstate her on the throne. This army was on its march from Hamilton to Dumbarton Castle (considered then impregnable), when it encountered the Regent Murray, who had concentrated his forces on the ridge of Langside Hill. As both armies were arrayed in heavy armour, when they met "each line of spears finally stuck in the angles and joints of the mail of the opposite rank, and the battle was a mere trial of superior weight and pressure" (Burton). It lasted three quarters of an hour, after which the Queen's men broke and fled. Three hundred of them are said to have been killed and only one on the other side! Mary, who had witnessed the battle from a hillock near Cathcart Castle, a mile and a half to the east of Langside, fled to the Borders, and took refuge in England. A memorial, composed of two granite slabs weighing about two tons, was erected by Earl Cathcart, on what is known as the Queen's Knowe, at Cathcart, to mark the spot from which she watched. A public memorial was put up in the village of Langside, at a cost of about £1000.

Routes from Glasgow

(1) To Bothwell, Hamilton, Lanark, and the Falls of Clyde (see p. 320).

(2) To Greenock, Gourock, and intermediate places on the Clyde (see p. 352).

(3) To Helensburgh, Craigendoran, and the Gareloch (see p. 414).

(4) To Holy Loch, Loch Goil, and Loch Long (see p. 343).

(5) To Lochs Striven and Ridden and the Kyles of Bute (see p. 352).

(6) To Ardrishaig, Inveraray, and other places on Loch Fyne (see p. 343).

(7) To Islay, Jura, Colonsay, Oronsay, etc. (see p. 363).

(8) To the Mull of Kintyre, Campbeltown (see p. 364).

(9) To Arran (see p. 346).

(10) To Paisley, Kilwinning, Ayr, etc. (see p. 328).

(11) To Girvan, Stranraer, and the Mull of Galloway (see p. 425).

(12) Stewart and the Wigtonshire district (see p. 460).

(13) Kirkcudbright, Castle Dougl&s, and the New Galloway district (see p. 454).

(14) To Kilmarnock, Thornhill, Dumfries, and intermediate places (see p. 444).

(15) Moffat and district (see p. 438).

(16) To Loch Lomond and the Trossachs (see p. 367).

(17) To Loch Earn, Loch Tay, etc. (see p. 380).

(18) To Fort William and the Caledonian Canal (see p. 414)

(19) The district of Appin (see p. 423).

(20) Oban and district (see p. 383).

(21) Mull (see p. 406).

(22) To the Hebrides (see p. 249).

(23) To Loch Awe (see p. 388).

TO BOTHWELL, HAMILTON, LANARK, FALLS OF CLYDE, ETC.

See Maps, pp. 326, 360.

Routes from Glasgow - Caledonian Railway - Central Station (both levels); North British Railway, Queen Street (low-level).

Days of Admission, Tuesday and Friday (10 to 4). Tuesday only to Bothwell when the family is at home.

The simplest way of combining Bothwell and Hamilton is to take train, North British or Caledonian, to Uddingston station. Thence walk to Bothwell Castle (1 m.), and thence another mile to Bothwell station (N.B.), whence take train to Hamilton (3 m.), returning to Glasgow from either station at Hamilton.

As far as Newton see main line p. 436.

At Newton, where the Hamilton branch leaves the main line, are the huge works of the Steel Company of Scotland, the first erected in Scotland for the manufacture of mild steel by the Siemens-Martin process. About 1-and-a-half mile to the east, across the river on the main line to Carstairs (p. 436), is the town of Uddingston (Hotel: the Royal), where there are many villas belonging to Glasgow merchants. About a mile from Uddingston is Bothwell. Bothwell Castle (Earl of Home) stands in a splendid position above the windings of the Clyde, and must at one time have been charming, but the thick smoke which drifts through the blackened atmosphere detracts greatly from the charm of the place. The Castle gate is open (south entrance) 10to 4 on Tuesdays, and there is a walk of about a mile up the drive before the modern mansion is passed. The ruined castle is built of that most picturesque of all materials in decay - red sandstone - and many a flowering plant and creeping shrub cover up its ruggedness. There are great round towers with battlements at the corners, and in the centre a space of smooth greensward encircled by the crumbling walls. Mighty beeches throw their branches through the breach in the walls, and the noble outlines of the pointed windows of the chapel may be traced on the river side, also the remains of the hall near the S.E. tower.

The tufted grass lines Bothwell's ancient hall.

The fox peeps cautious from the creviced wall,

Where once proud Murray, Clydesdale's ancient lord,

A mimic sovereign held the festive board."

The castle was built in the 13th century and partly rebuilt in the two succeeding ones; the great donjon belongs to the earlier period. It was captured by Edward I., who gave it to Aylmer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke. In 1377, after a strenuous and destructive siege, it was retaken by the Scots. It was held by the Douglases until 1445.

Across the river is another fragment of ruin, which is all that remains of Blantyre priory, founded in the 13th century. David Livingstone was born in the village of Blantyre, which is two miles away in the midst of the coal and iron district.

Half a mile from the castle gates is the village of Bothwell. The Church is worth seeing, for part of it is old, and though lately restored, it has not lost its charm, for the work has been well done. In front is a very ugly mosaic monument to Joanna Baillie, who was born in the manse, her father being the minister. The Duke of Rothesay, of whose terrible fate Scott gives an account in the Fair Maid of Perth, was married in the old church to a daughter of Archibald Douglas the Grim. Half a mile beyond the village is the famous Bothwell Bridge where, in 1679, the encounter between the royal troops under the Duke of Monmouth, and the Covenanters took place, when 500 Covenanters were killed, and as many again taken prisoners. The bridge is modernised, and a monument has been put up in late years at the north end in memory of the Covenanters, (see Old Mortality). The grounds stretching from the bridge along the north-east bank of the river, were part of the estate of Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh, who assassinated the Regent Murray. It was a hawk's flight of land granted according to the old custom to his ancestor for valour. Hamilton (twelve miles south-east of Glasgow and two from Bothwell) is the capital of the Middle Ward of Lanarkshire, and an ancient parliamentary burgh, with 32,775 inhabitants. It formerly carried on a considerable trade in weaving and tambouring, but now it depends chiefly on the mineral wealth in the midst of which it is situated. It used formerly to be noted for its flower and fruit gardens. From the bridge in the principal street we see a new building - a Masonic Lodge, and also the Carnegie Free library. From this point the chimneys of the Palace may be seen over the house roofs to the left, and a little away on the right is the tower of the ugly Parish Church, which, however, was built by Adam, The centre of gravity of the town has been shifted many times in accordance with the reigning Duke's ideas. The oldest village was called Netherton, and of this there remains only a cross not far from the Mausoleum in the Palace grounds (see p. 323). The next town sprang up around and very near the Palace, and by turning down to the left just before the bridge aforementioned the long winding main street of this may be reached. It is now wretchedly poor, and the strange feature may be noted that when the exclusiveness of the reigning dukes resented the nearness of their poor neighbours this town was thrust away. The fine building, once the inn, where Boswell and Johnson stayed, is now enclosed within the high encircling wall and is used as estate offices. The old Town Hall or Tolbooth with its quaint tower still remains, though disused, and the houses which formed the side of the street near the Palace still stand, with windows blocked so that they form a wall.

The Low Parks are open to the public free twice a week, on Tuesday and Friday from 10 to 5. On other days orders of admission can be obtained at the Estates Office, which is at the Palace. Here also orders are issued to admit visitors to the High Parks of Hamilton (see below).

The Palace itself is very close within the wall at the point noted, a classical museum-like building, of two dates. The north side and wings, which were built on to it about 1880, have all the hideous massiveness that characterises that period. The portico is of the Corinthian order, after the style of the Temple of Jupiter Stator at Rome. The 12 pillars are 60 ft. in height, and are formed of solid blocks of stone, quarried in Dalserf; each required 30 horses to draw it to its position. The southern front is much simpler.

The interior was divested of all its treasures except those that were entailed, by the late Duke; pictures, the Beckford library, the very tapestry from the walls were sold; even the marble staircase would have gone had it not been found impossible to uproot it. On the east side, where a green lawn with flower beds now is, used to stand the old Collegiate Parish Church; of this the Dean of Glasgow was rector ex officio; not a stone remains.

Looking from the south part we see the moulded iron parapet and sunk road to Motherwell, built by the Duke to replace the ancient road, which ran right past the front of the Palace. High on the hill at the end of the vista are the buildings, stables, dog-kennels, etc., on the site of the old Palace of Chatelherault. About 2 miles south-east of Hamilton, within the western high park, are the ruins of Cadzow Castle (the original baronial residence of the Hamilton family, and the subject of Scott's spirited ballad), which occupy a site overhanging the river Avon. In the chase are the ancient oaks, the remains of the Caledonian Forest, where browse some of the breed of Scottish wild cattle, of the same breed as those still preserved at Chillingham.

Turning now northward we find the Mausoleum (key at keeper's cottage, close by). The general design is that of the Emperor Hadrian's Tomb at Rome. Under the floor are vaults, arranged according to the fashion of a catacomb. The rustic basement contains effigies of Life, Death, and Eternity, each personified by a human face. The chapel doors are formed of bronze panels, copied from the famous Ghiberti gates at Florence. The floor is a beautiful mosaic of rare and costly marbles, granites, and porphyries.

The builder himself lies interred in a sarcophagus of green syenite brought from Egypt, said to be 5000 years old, and for long popularly supposed to be that of Pharaoh's daughter. It stands on a pedestal of black marble. But the most interesting point about the Mausoleum is the extraordinary vibration which prolongs and carries on any note uttered in the building with marvellous sweetness. Not far from the Mausoleum is a clump of trees on an eminence called Moat Hill, which is near the site of the oldest village.

The modern town of Hamilton covers a considerable extent of ground. It contains a town-hall, a suite of county buildings and court-houses of an earlier date, and an extensive range of military barracks. The Dutch gardens of Barncleuth, constructed in terraces on the steep banks of the Avon, 1 mile S.E. of the town, with their fantastically trimmed shrubbery and general quaintness of furniture, are curious. The gardens were laid out by John Hamilton, an ancestor of Lord Belhaven, about 1583. Dorothy Wordsworth, whom nothing escaped, speaks of it in her journal as "a little hanging garden of Babylon."

Seven and a half miles south of Hamilton is Strathaven with the ruins of the Castle of Avondale. About 7 miles north of Hamilton are Coatbridge (pop. 37,000) and Airdrie (pop. 22,300), the very foci of the iron trade. There are more blast furnaces and a greater output of iron in proportion to the area in this region of Scotland than in any other in the world. The manufacture of malleable iron, iron wire, and all the heavier metallurgical industries are carried on extensively at Coatbridge.

If possible, it is best to cycle from Hamilton to Lanark, as the two, or with the addition of Bothwell, the three places can easily be seen in a day; but for those who merely want to see the Falls of Clyde, the route from Glasgow is given below. From Hamilton there is a good road (14 miles) all along the valley of the Clyde, noted for its orchards. Between two and three miles before reaching Lanark a sign-post on the side of the road shows the way to the Stonebyres Fall, which stands by itself on this side of the town, and for size and beauty comes second of the three. For the others, and also for Tillietudlem, etc., see p. 326. Before reaching Lanark by road there is a stupendous hill to climb.

LANARK

Hotels: Clydesdale (C); Station; Black Bull. Pop. 6500. Eighteen-hole golf course.

Route. - Train from Glasgow (Central Station); Edinburgh (Princes Street Station);

Coach from Lanark Station to Upper Falls, returning to Lanark for lunch;

Coach from Clydesdale Hotel to Cartland Crags, Stonebyres Fall, and

Craignethan Castle; Train from Tillietudlem Station.

Lanark is an ancient town; it was in existence in the time of the Romans, and its castle, now remembered only by the names of Castlegate, etc., was a royal residence. In the town steeple is a bell, still in use, with the date 1100 on it, also a silver bell, said to have been the gift of William the Lion, which is annually competed for at the September race meeting. The ruins of the old church, which are a little way from the town, are also undoubtedly ancient. As it is to-day, Lanark is a very quiet little county town with some features peculiar to itself. The main street is very wide and slopes uphill steeply. In certain states of the atmosphere, the glow of the setting sun catches it, and bathes it in a peculiar glory, which was remarked by Dorothy Wordsworth when she visited the town in 1803, and which is still notable. The town stands on a great height and has to be approached by weary hills; down in the valley below are the large cotton mills of New Lanark. Lanark was the scene of many of William Wallace's exploits, and a statue of the patriot, as bad as they usually are, stands over the entrance to the parish church.

In 1293 Wallace was engaged in a street scuffle, and subsequently had to fly before the English Sheriff Heselrigg; while he was away Heselrigg seized and killed his wife, which brought Wallace down upon him in the night, and was the cause of an uproar ending in his well-deserved death.

At the high end of the town are the race-course and a small loch where pleasure boats can be hired. The Lanark bowling- green is celebrated.

The Falls of Clyde

The Falls are difficult to see, and the effort to do so entails a great deal of walking even at the best. There are three of them, as already stated, viz. Stonebyres, Corra Linn, and Bonnington. Of these the first is three miles away on the Hamilton road, and must be seen en route to Tillietudlem Station, while the other two are in the neighbourhood of the town in private grounds, and those who are not already provided with the tour tickets of the railway must get tickets at the lodge (sixpence). The road to the Falls leads south-west from the town, and goes down a very steep hill. Those who are cycling will find it best to make a complete detour through New Lanark, turning back on their tracks by the river. Cycles are permitted as far as the second lodge, where they may be left. If preferred, the Falls may be viewed from the south-west side of the river, where the same formalities are observed; the way here is worse, and the view of Corra not so good, though that of Bonnington is better. On each side a raised path runs through woods for about half a mile before we arrive at Corra Linn. The whole of the river Clyde, of considerable width here, flings itself over a drop of eighty-four feet into a deep basin at the turn of the channel, and the effect is marvellously fine. The banks of the river are clothed with birch and ash, oak and hazel, and the setting adds much to the falling water. Wordsworth's ode to Corra Linn beginning:

The dullest leaf in this thick wood, quakes - conscious of thy power,

is well known.

Bonnington Linn is about a mile farther on. Near Corra Linn stands a fragment of Corehouse Castle, on a fine cliff with perpendicular sides, and the way to it lies by pleasant pathways beneath shady trees. Part of the Linn may be crossed by a bridge resting on a small island. The river here only drops thirty feet, but sweeps round in a great circle, and then flows along in a deep gorge to Corra. Bonnington House, in the grounds of which the Falls are situated, was built by Sir John Ross, the naval explorer.